In honour of our new exhibition, Papal Parchments and Blackletter Books, here’s a lesson on how medieval manuscripts were made, courtesy of the exhibition’s curator and a student in UBC’s School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies, Robert Makinson.

How Manuscripts Are Made

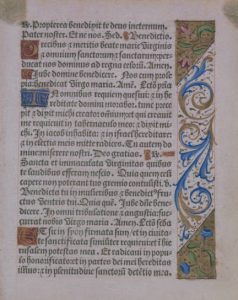

Manuscript leaves are usually made from vellum, a term denoting calfskin; other animal skins were also used, however, and these are properly called parchment. Their material makes manuscript pages much thicker and heavier than paper, so they resist tearing and other forms of trauma better, but they react badly to changes in temperature and humidity: this causes the wrinkles and wave patterns you sometimes see in damaged manuscripts.

When the animal had been skinned, the material was submerged in a lime solution for several days, which prepared it to receive inks and pigments; afterwards it was stretched upon a wooden frame to dry evenly. Then pages were cut from the skin, and the artisan used a knife to remove hair from the “outside” of the skin and a pumice stone to reduce imperfections. If you look carefully, you can actually tell which side of the skin you are looking at, thanks to scars, veining, and other marks! Usually, these sheets were folded one or more times, creating what we call folios or quartos; many were gathered and bound together to make the manuscript. The front and back of each sheet were called the recto and verso, respectively.

There were several kinds of inks used during the medieval period:

- Similar to modern inks because they adhere to the surface of the material, carbon gums were used for most early manuscripts, and were made by mixing carbon-based materials like charcoal or lamp-black with a thickening agent like gum arabic.

- Later manuscripts were usually written with iron galls, which were made by combining tree galls, usually from oaks, and iron from nearly any source. They were much more cheaply made and used almost exclusively in the later Middle Ages, but they can cause more damage to manuscripts and fade to brown over time. Most manuscripts in this exhibition were written with iron gall inks.

- Red inks were made by pouring acidic substances like vinegar or urine on lead sheets and repeating the process until the desired hue was achieved. The process usually took several weeks, but since red inks were necessary for rubrication, this was a fairly common practice.

- There are dozens of different medieval recipes for making other colours of ink, and they vary widely in materials and manufacturing processes.

Pigments were used for illuminated manuscripts that feature colourful illustrations. Our collection does not have much illumination, but like coloured inks, these pigments come from a wide variety of sources: some were naturally-occurring compounds, while others were manufactured artificially. Certain pigments have weathered the years better than others, since they can fade, dissolve, or even explode without proper storage conditions!

To see some of these incredible documents in person, please join us for the exhibition Papal Parchments and Blackletter Books: How the Middle Ages Shaped the Way We Read, 1245 AD to UBC, which runs from May 1-31, Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. at Rare Books and Special Collections on the first floor of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre. For more information, please contact Rare Books and Special Collections at 604 822-2521 or rare.books@ubc.ca.