Show and Tell: Selections from our Personal Archives and Libraries

How we remember, and what we hold dear, differs from person to person. All of us have personal archives we keep to preserve memories that are precious, that document our families, our histories and record important events. It could be a simple piece of ephemera we love and cannot part with (a ticket stub from our first concert, for example), or photographs of ancestors that offer clues to our origins, or anything we have set aside and saved for a myriad reasons. Similarly, our personal libraries hold volumes that have emotional value to us, not just for the words contained in it, but as a reflection of a time in our lives, we found them particularly relevant. This could be the first book of poetry that made us fall in love with verse, or the dog-eared copy of a classic novel that led us to our current passion for libraries and library work. This blog series explores selections from the personal libraries and archives of members of the Rare Books and Special Collections team, and other colleagues from UBC Library and beyond. We hope our stories will help you reflect on what is meaningful at this time in your, and in our, collective histories.

— Krisztina Laszlo, Archivist

Weiyan Yan, Office, Copying & Shelving Assistant

In her late teens, my mother was a nurse at a hospital in Xi’an city. After she moved to my father’s hometown – a small village on the Loess Plateau – she became a doctor and a midwife. At that time in China, people called this kind of doctor “Barefoot Doctor”. That meant they were farmers but they were also doctors in their spare time. Even I’m not sure about the qualifications. She said that she was “a flagpole pulled out from a bunch of chopsticks”. But as far as I know, she did a very good job, especially at being a midwife. I still remember that she had a red bag for being a doctor. It was the most important thing in our house and we never were allowed to touch it.

Chinese medicine bag

I don’t know how many patients she had seen, but I know that from late 1950s to late 1990s, she delivered most of the babies in our village, the parents and then their children, except a few that she felt should be delivered in the hospital. She was well respected and she became an older sister-in-law to many people in our village. That was confusing! They called her sister-in-law out of respect, and I called them grandparents or great grandparents because of the hierarchy in our society.

I have many memories from when she was working. In the middle of the crazy, cold, winter night, someone looking for my mother’s help would loudly knock on our front door or back door, or sometimes even both doors; everybody in my family woke up. My mother would take her medicine bag and leave with them right away. Most of the time, she would come back the second morning with a few thin, dry pancakes. I would have a piece of them and squat beside her to watch her washing her rubber gloves. I forget most of the details, and only remember that she turned them over, blew some air in, tied the open side with one hand, and squished with the other hand. It was so amazing to me at that time that the fingers would come out one by one with popping sounds. Sometimes my father might come by and offer to bite my pancake into the shape of a horse – I was born in the year of the horse. I was really happy at first and then cried when there was only a small piece left.

My mother was a city girl. After she moved to the village, she learnt everything about being a farmer, or being a woman on a farm. She spun, wove, made clothes and shoes for us. But the soles that she made were never good. She used a hammer to make them flat on a piece of stone.

I was proud of my mother, but not always. When she came to our school for the immunizations, I was always the first one to get an injection in order to set a good example for the other kids, even though I was also very scared. When she dressed up and played a bad woman on stage, I was so embarrassed in front of my friends. I wanted her to play a hero. But I never discussed that with her. I was a good girl at that time.

My mother has been gone for many years. Each time when I’m thinking of her, I always picture her with her red medicine bag, coming to me with a smile.

Natalie Trapuzzano, Student Archives and Reference Assistant

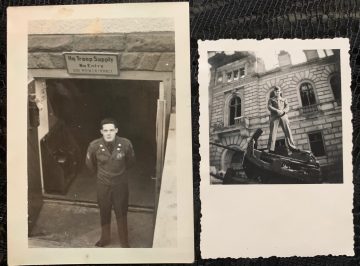

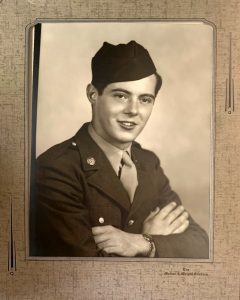

Stushie’s headshot in uniform.

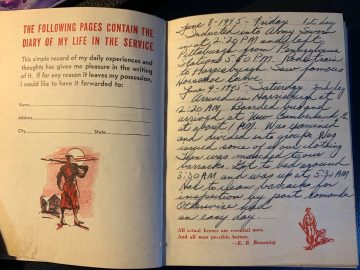

I can say without any hint of humor or irony that one of my best friends is a ninety-three-year-old man. My great-uncle Stushie (Stanley, if you’re being stern) is my hands-down favorite person. A proud WWII veteran, history buff, perennial jokester, and armchair Jeopardy champion, he’s been the most consistent and inspiring man in my life. Even though he was a high school dropout, he’s the most intelligent and well-read person I know and always encouraged me to work toward the same. He bought me annual subscriptions to National Geographic and Smithsonian Kids magazines until I got old enough for the “adult” versions that he still sends me today—and no one leaves his house without a bag full of random items to go. He’s a bit of a packrat and his favorite topic of discussion is his experience in Europe during WWII, so he’s given me a lot of his military-related photos and ephemera over the years. He recently had to move to an assisted living facility, and I’ve been worrying about him a lot because of the pandemic’s impact on seniors in the United States, so it’s nice to have some of his treasures around while I can’t be with him in person.

- Some snapshots from his time in Europe. Notations on the back: “Some more clowning around” (left); “Me, standing on an AA Gun with what’s left of the Propaganda Ministry in back” (right).

- A canvas pouch that was part of his military uniform, as well as a compass and his personalized stamper that were carried within it.

- A ring bearing the symbol of the 78th Infantry Division from his time in Berlin & a hand-poked ring his brother Leonard traded a pack of cigarettes for while stationed in Africa during WWII.

- A page from his military diary, begun June 8th, 1945.

- One of our favorite pastimes: making the other person draw increasingly ridiculous pictures.

- Natalie and Stushie