Content warning: The following blog post discusses homophobic attitudes and laws in a historical context.

Many thanks to guest blogger Matthew White for contributing the below post! Matthew is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and has completed both a Co-op position and a Graduate Academic Assistant (GAA) position with RBSC.

This is part of an ongoing series of blog posts that gives students and RBSC team members a chance to show off some of the intriguing materials they encounter serendipitously through their work at RBSC.

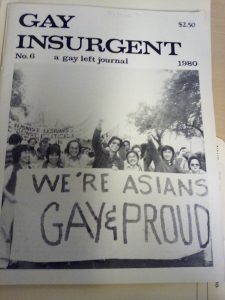

As a queer man, it was with a great deal of excitement that I was asked to finalize the processing of the Archives Collective collection at Rare Books and Special Collections. The Archives Collective, a predecessor of both ArQuives (formerly Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, and Canadian Gay Archives) as well as the BC Gay and Lesbian Archives, collected widely over their short tenure, much of it related to the deeply political lives of gay men and women in the 70s and 80s.

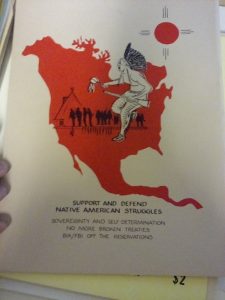

This collection was at times gut-wrenching in the displays of homophobia, at times brought me to tears because of the solidarity between marginalized communities. There were some consistent themes throughout the collection that I would like to share, particularly as they relate to queer lives in the world today.

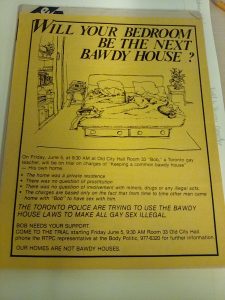

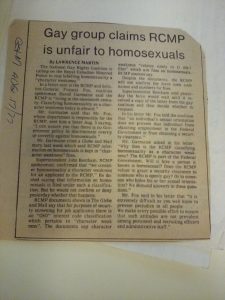

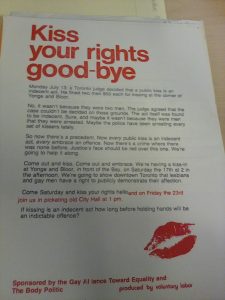

The first thing I want to stress is that the RCMP and the Canadian legal system have never been friends to queer people, not to mention working people, women, First Nations, and immigrants. They will uphold whatever laws are in the books – if these laws discriminate against gays, so be it. The number of times that the RCMP overstepped by entrapping gay men having sex in their own homes, by keeping files on notable queer activists as potential enemies of the state, not to mention NDP leaders, prominent feminists or Indigenous activists, by physically accosting queers in the streets was staggering.

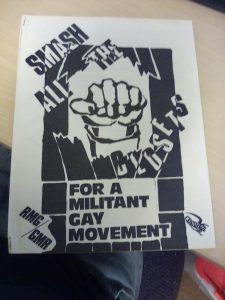

Obviously, queers did not go down without a fight – a fight that we are still fighting to this day. Gay militancy spread rapidly, with groups like the Lavender Panthers prowling streets to protect queer people. Protests were staged rapidly, and long running education or legal campaigns were effective in bringing these issues into the public eye.

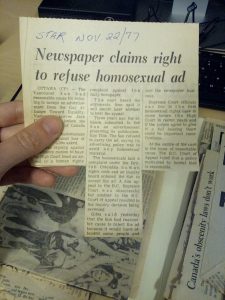

It was not difficult, though, to see how these kinds of attitudes were maintained for so long. One pamphlet by the League Against Homosexuals (LAH) said, “Queers exist to seduce and pervert our children. Queers are sexually depraved vampires. If queers are allowed to have “equal rights” then they MUST be allowed to seduce your child.” I am still confused as to why equality necessitates molestation, but this was perhaps only the most glaring example. The Toronto Star and the Vancouver Sun often refused to advertise for gay magazines, leading to a legal battle by the Vancouver Sun in the mid-70s that they won in the Supreme Court of Canada. It was noted that it might offend readership, so it did not have to be included.

An article in an unknown newspaper by McKenzie Porter notes “Many homosexuals are no longer satisfied with acceptance, sympathy and freedom from prosecution. They now seek approval acclaim and authority. The propaganda of homophile associations both female and male, reveals undisguised aspirations to political leadership.” Porter goes on to say that gay men and women are unfit for politics because of “a neurotic or psychotic state of paranoia associated, for reasons unknown, with a childhood history of anal eroticism.”

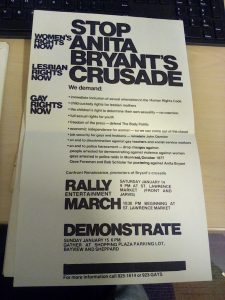

The Star, after being accused of homophobia, made the following statement: “… we stop short of encouraging the spread of homosexuality. We have no wish to aid the aggressive recruitment propaganda in which certain homosexual groups are engaged, and we strongly oppose those who seek to justify and legitimize homosexual relations between adults and children.” Like current legal oppression against trans people, children were often the basis of homophobic attacks. Other examples include a well-documented campaign by Anita Bryant to halt the gay liberation movement, by using children’s safety and wellbeing as the basis of her homophobia.

It was this kind of push back that brought gay people back onto the street, time and time again. It was a dynamic period, full of fundraising dances, highly publicized legal battles, and periodicals that discussed gay issues – anything from criticism of Marxist attitudes towards homosexuality to letters of support by brothers and mothers to their trans daughters, from rallies against racial discrimination experienced by taxi drivers, to graphics protesting the treatment of Indigenous peoples across North America.

You’ll also note the absence of trans people in my descriptions of the archive – they are, unfortunately, notably absent. Then, as now, often trans people found difficulty finding welcoming environments, and focus on liberation was often focused exclusively on sexuality without engaging critically with transgender or transsexual issues.

For myself, as an aspiring archivist and as a gay man, this was an incredibly enlightening experience. Many queer people have noted the generational absences that exist in our communities due to AIDS and other issues, including suicide and the return to the closet that can occur as queer people age. Being able to access so much of the knowledge and experience of queer people through the archive feels so important. These were people who knew what needed to be done to enact change, and all of that information is still at our fingertips. If we can’t talk to our queer ancestors, then maybe we can learn from what they left behind.