Show and Tell: Selections from our Personal Archives and Libraries

How we remember, and what we hold dear, differs from person to person. All of us have personal archives we keep to preserve memories that are precious, that document our families, our histories and record important events. It could be a simple piece of ephemera we love and cannot part with (a ticket stub from our first concert, for example), or photographs of ancestors that offer clues to our origins, or anything we have set aside and saved for a myriad reasons. Similarly, our personal libraries hold volumes that have emotional value to us, not just for the words contained in it, but as a reflection of a time in our lives, we found them particularly relevant. This could be the first book of poetry that made us fall in love with verse, or the dog-eared copy of a classic novel that led us to our current passion for libraries and library work. This blog series explores selections from the personal libraries and archives of members of the Rare Books and Special Collections team, and other colleagues from UBC Library and beyond. We hope our stories will help you reflect on what is meaningful at this time in your, and in our, collective histories.

— Krisztina Laszlo, Archivist

Eleanore Wellwood, Technical Services Library Assistant, Xwi7xwa Library

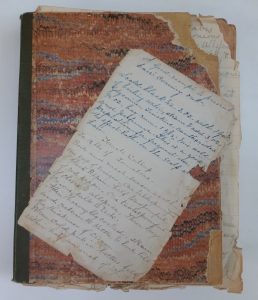

I have my grandmother’s recipe book (Helen/Ellen/Nellie Whittington Wellwood, 1883-1969). It probably started life as her mother’s (Emeline/Emily Tuffnell Whittington, 1845-1941). It was never pretty and now is falling apart and the paper is brittle. The reason it is a treasured possession is only because of how one recipe leads off into questions and clues about family history and local BC history and world history and the great unresolved Canadian culinary debate about the origin of Nanaimo bars.

The history of Nanaimo bars is reasonably well documented (according those emergency reference sources, Google and Wikipedia). The earliest documented use of the name “Nanaimo bars” was in the 14th edition of the Vancouver Sun’s Edith Adams’ Cookbook (which UBC Library does not have). Many possible precursors have been proposed. Some even have a connection to Nanaimo and more specifically to a United Church cookbook from Nanaimo. But, as every reference librarian knows, it is hard to search for something without a known name and with nothing but common search terms, so maybe all the precursors have not been found.

My family history is also reasonably well documented but with unasked or unanswered questions. Emeline was born in the Southampton workhouse, a piece of information she did not share. She married William Whittington, a bricklayer from the Isle of Wight, in Chatham, Kent, England in 1868. They converted to Methodism and embraced temperance and proceeded to move north and to have children until ending up in Seascale, Cumberland, where Nellie was born and her father went bankrupt building the Methodist church there. In 1889, Nellie emigrated with her mother and four siblings to join her father and oldest brother, who had emigrated the year before to Victoria. After an interlude in Port Townsend and Port Angeles, they settled into the circle of Methodist, temperance-supporting builders in Victoria with their social life centred on their church. My father’s father, Wilmot Bryant Wellwood (1883-1972), was born in Wingham, Ontario where his family was on an extended visit ‘back home’ returning from a move, with stays, through Peoria, Illinois, San Francisco, New Westminster, Nanaimo, Point Atkinson, and the Naas River and before returning (again via Peoria and San Francisco) to New Westminster, Nanaimo, and, finally, Victoria. My great grandfather had many occupations but his strongest wish had been to be a Methodist missionary. Their social lives also revolved around the Methodist church wherever they lived. The United Church of Canada Archives in Vancouver provides more than enough evidence of both families’ connection to the church and how important its social activities were to young people in the early twentieth century.

My grandparents were neither rich nor poor. They had their share of family difficulties, including the death of both their fathers in 1912 and the ‘sharing’ of both their mothers with other family members for many years. They had four sons, one of whom died at birth in 1917. My grandfather stayed employed during the Great Depression, weathered rationing and the death of one son in World War II, saw two sons through university, married and starting families after the war, supported relatives who had fallen on hard times several times, and ran a precursor of a Bed & Breakfast, leaving them frugally comfortable in retirement in the early 1950s. All of this creates the backdrop for the recipe book.

My recipe book is a book of mysteries. It might have been two books because there is a clump of lined pages with no red margin line still bound together but separated from the binding. Almost all of those pages are blank. There is another clump of pages which are still sewn in and with the red margin line. More of these pages have recipes until about halfway through, when it also goes blank. Together the two clumps seem to be a little too big for the spine binding and yet seem to belong together. There is no apparent organization. There are few dates (included by happenstance) and no page numbers. Like most family recipe books, it is a combination of handwritten recipes and loose and pasted-in newspaper clippings and recipes written on scraps of paper and envelopes. If there ever was an order to these, it is long lost. The handwriting changes, the inks change, some recipes are clearly written by others and some suggest the aging of the writer. There are snippets of things the owner wanted to save – hand copied or cut from a newspaper – now-or-always-corny jokes and inspirational poems and useful recipes for preventing hair loss. There are far more recipes for desserts than anything else. Most of the recipes reflect the limited range of available ingredients and a distinctly British palate.

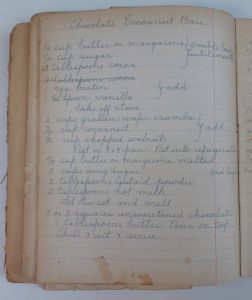

Following the recipe for Dreamland Cake and before Unbaked Chocolate Brownies, there is a recipe for Chocolate Coconut Bars. In everything but name, it is a Nanaimo bar. My limited paleography skills lead to me to believe that Nellie added the recipe and that it would have been after wartime rationing, but also after her boys had left home, while her handwriting was still firm and steady but before the advent of ballpoint pens – or the early 1950s. It would have been the ideal contribution to United Church social events of the time. But, was it the ideal recipe before or after the christening of the Nanaimo bar? I do not know. All I know is that Chocolate Coconut Bars don’t appear to be one of the precursor names, and Victoria and Nanaimo aren’t all that far apart.