Many thanks to guest blogger Brandon Leung for contributing the below post! Brandon is a graduate student in the Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management program at Ryerson University and completed an archival internship with Rare Books and Special Collections in December 2020.

A few years ago, I had what turned out to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity at Rare Books and Special Collections. During my time as an undergraduate at UBC, I took a class about archives that had us visit RBSC every week to look at a different collection held there. One time, we had the chance to actually hear from one of the donors themselves, the late Chinese Canadian artist and activist Jim Wong-Chu. During that class, he talked continuously, without pause, about Chinese Canadian activism and history, an ability he was well known for. Afterwards, he showed us an album, titled Pender East, that contained both photographs and handwritten poetry. As a student who was, and still is, interested in the intersection of text and photography, this album amazed me. The photographs were skillfully printed, depicting people and places in Vancouver’s Chinatown, while the poems spoke about the Chinese Canadian experience. I would come away from this class with the album still on my mind and it unknowingly became the first and last time I would see Jim Wong-Chu in person. A couple of years later, I would find out that he unfortunately passed away. Yet Pender East still remained on my mind enough that over this past year, I decided to write about it for my final thesis paper for Ryerson University’s Film + Photography Preservation and Collections Management program, done alongside an internship at RBSC. In the following blog post, I would like to talk about some discoveries I made along the way. Though the COVID-19 pandemic hit in the middle of my research, I fortunately still found out several things about the album from a variety of sources, including Jim Wong-Chu’s fonds, YouTube videos of him and individuals who knew him personally.

Jim Wong-Chu, Pender East, photographic album, [after 1970?] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

One interesting fact I discovered about Pender East was that it was partly a collaborative work, which fit into the community-based activism that was going on at that time. For example, the poems included in the album showcase this. Though Jim Wong-Chu wrote many of the poems (a few which would appear in his later poetry book, Chinatown Ghosts), one about a grass dragon performance was written by his friend and fellow Chinese Canadian cultural activist Paul Yee. Additionally, the poems as they appear in the album were handwritten by another one of his friends, Cynthia Chan. Both Yee and Chan are named in the album’s final acknowledgement page, though the nature of their contributions isn’t revealed in the album itself. Fortunately I was able to speak with both of them and learned about their contributions.

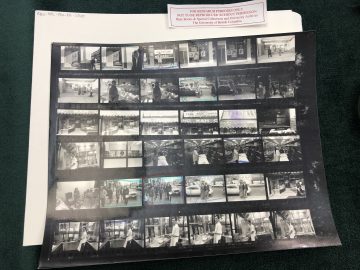

Information about photographic prints, especially prints made in the pre-digital age, can also be found in contact sheets and film negatives. The Jim Wong-Chu fonds contain a large amount of these materials and I was fortunate enough to go through a box of them. One thing that can be said about archival materials is that they provide material evidence of the past and this box of negatives and contact sheets provided material evidence for some of the things I was learning about Pender East.

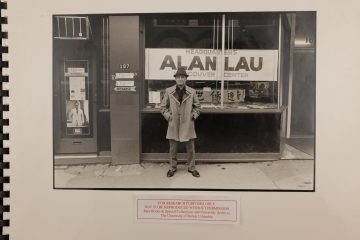

By looking at these materials, I was hoping to find some of the photographs in Pender East within these contact sheets. Contact sheets are helpful documents of a photographer’s practice because they show single rolls of film on one piece of photographic paper. We can then assume that all the photographs on one contact sheet were photographed in close proximity to each other. For example, I found the following photograph of a man standing in front of an election campaign headquarters in one of Wong-Chu’s contact sheets (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2740).

- Jim Wong-Chu, [Chinese man standing in front of Alan Lau headquarters] from Pender East, gelatin silver print, [after 1975] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

- Jim Wong-Chu, [East Pender street contact sheet], gelatin silver print, [after 1975?] (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2740, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 33)

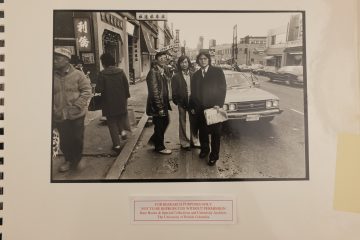

I also discovered that this specific contact sheet contained a majority of images that were included in Pender East. By looking closely at the photographs, and from what interviewees told me, I was also able to figure out where some of these photographs were taken. The above photograph was taken at 107 East Pender Street (seen in the photograph), while a photograph of three men posing on the street that appears later on the contact sheet was taken in the 200 block of East Pender, a known commercial hub of Vancouver’s Chinatown at the time (as identified by interviewees). This material evidence of Jim Wong-Chu’s photography and his photographic practice corroborated what I had been told in interviews, that he spent many days walking through Chinatown, up and down East Pender Street, and photographing.

Jim Wong-Chu, [Two unidentified men and Charles Mow] from Pender East, [after 1975] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

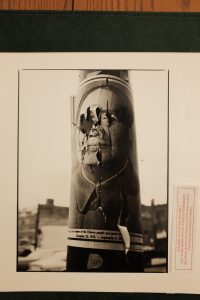

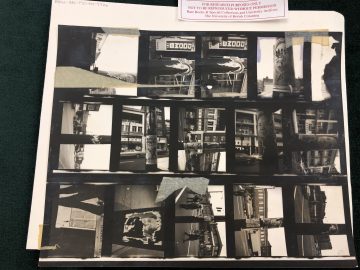

Another striking image in Pender East appears halfway through the album. It is a close-up of a poster of Mao Zedong, leader of the People’s Republic of China, torn at the eyes, pasted onto a street pole in Chinatown. Through my research, I also discovered this image corroborated another story related about the Chinese Canadian community. In a video recording of a poetry reading Jim Wong-Chu did at the Roedde House Museum, he discusses the story behind this photograph. After Mao died in 1976, supporters of the People’s Republic of China put up posters depicting him around Vancouver’s Chinatown. Soon after, supporters of the opposing Kuomintang government (The Chinese Nationalist Party, based in Taiwan, who claimed to be the rightful rulers of China) tore up the posters and Wong-Chu photographed the results. Wong-Chu also decided to use this photograph on the cover of the first edition of his poetry book Chinatown Ghosts, which he said drew the ire of both camps. In his fonds, I found a contact sheet containing the image in question, plus photographs of other torn Mao posters throughout Chinatown (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2766). Again, his contact sheets acted as material evidence of Chinese Canadian history and, alongside Wong-Chu’s own story, gave me insight into another side of the community that I would not have known from Pender East itself.

- Jim Wong-Chu, [Torn poster of Mao Zedong] from Pender East, gelatin silver print, [after 1976] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

- Jim Wong-Chu, [Mao posters contact sheet], gelatin silver print, [1976?] (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2766, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 33)

By the end of my research, I had made many more discoveries about the Chinese Canadian community and Vancouver’s Chinatown in the 1970s, too many to be fully listed here. Of course there are many more to be made and I hope my work so far can act as a stepping stone into more research for one of the most accessed collections at RBSC. I feel privileged to have been given the opportunity to work on Pender East, learning more about Chinese Canadian history and Vancouver’s Chinatown and helping stoke some old memories.

(Through all my scrutiny of the photographs in Pender East, from my interviews and other archival photographs of Vancouver’s Chinatown, I also created a Google “My Maps,” pinpointing some of the locations where Wong-Chu’s photographs were taken.)