Many thanks to guest blogger, Barbara Towell, for contributing the below post! Barbara is University Archives’ E-Records Manager and an enthusiastic collector of antiques. This post continues an occasional blog series looking at 19th century photographs of women and their jewellery held in Rare Books and Special Collections.

The art of framing memory: Hannah Maynard and the impossibly large brooch

Among the many items included in the Uno Langmann and Family Collection of British Columbia Photographs is this remarkable cabinet card created by Hannah Maynard, a 19th-century Canadian businesswoman, artist, and celebrated photographer. In 1862 Maynard’s business opened in Victoria in the Colony of Vancouver Island and remained in operation until 1912. Her clientele was said to be the well-heeled of Victoria, but as Dr. Jennifer Salahub tells us, Maynard photographed its inhabitants across economic classes (Salahub, p. 171). Maynard is most recognized for her experimental photography leaving her portraiture to be sometimes described as conventional. But in this image, I think Maynard achieves something quite unconventional. Crossing the boundaries of the photographic frame, something she is known for in her experimental photography, Maynard uses the subject’s jewellery to connect past artistic practice with the technology, and most importantly, the art of photography.In this cabinet card we see a portrait of a mature woman looking at the camera. She is dressed in black, wearing a ribbon bonnet, a watch chain, and an impossibly large brooch. The scalloped edge of the card stock suggests a time period of 1890s but the brooch is from an era prior. The pin was new around the time known as the Grand Period of Victorian jewellery (1861-1885). Fashion trends during the middle part of the 19th century favoured jewellery large in scale. Brooches were especially popular and were typically around 6.35 x 3.81 centimetres in size, roughly three or four times the size of pins popular in the period this photo was taken.

The brooch is known as a Swiss enamel. Drawing on a tradition centuries old, Swiss enamels were admired souvenir items handmade by highly skilled artists. The mid-century’s custom for large articles of adornment provided enamel artists ample scope to create a window framing an idealized time and place. They were status symbols of wealth and most importantly, Anglocentric class-based concepts of sophistication that could only be achieved through European travel. For affluent 19th-century tourists visiting Switzerland they made the perfect portable keepsake memorializing travel while signalling wealth and refinement.

Example of Swiss enamel showing colour saturation c1860. Photograph used with permission from Nelson’s Rarities.

What this cabinet card cannot show the viewer is the vibrancy of the brooch. Set against the black backdrop of the subject’s dress, the decorative frame, its saturated colours and impressive size would have made it the outfit’s focal point. And while I am unable to enjoy the colours of the pin 160 years later, I am still unable to keep my eyes off it. But this, I believe, is the central point.

Swiss enamels are very much part of a world before popular photography and it was specifically the new medium of photography that severely reduced the luxury tourist trade in Swiss enamels. In contrast to the Grand Period, brooch styles by 1890s had become comparatively small. This brooch is at least 20 to 30 years old at the time the photo was taken, even for a slow-moving colonial outpost such as Victoria, its inclusion seems somewhat odd; not old enough to be an antique, but not fashionable either. It is possible that the subject may have chosen this particular brooch herself without counsel from Maynard, however, photographic portraiture was a formal process in this period and the photographer’s use of visual support contextualizing the subject was common practice. The brooch’s position in the photograph effectively ties the subject to a bygone era. It is the key prop in this cabinet card and it is important that it be front and centre. The brooch’s centrality is the principle reason the bonnet is left untied, so as not to disrupt the viewer’s sight-line. The pin’s inclusion not only situates the subject in the past however, it also buttresses another narrative fundamental to Maynard’s contemporary artistic practice.

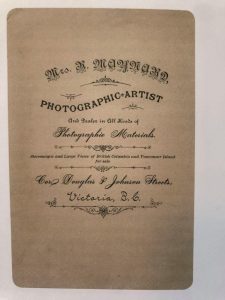

Most other cabinet cards use either the back or the block at the bottom of the card to advertise the name and location of the business. In this example the company information along with the words, photographic artist is printed on the back of the card. Maynard annotates the front of this card by hand, and that addition is unusual. She writes her married name, Mrs. Richard Maynard, and her occupation, Artist. Unlike other cabinet cards, Hannah Maynard presents herself not primarily as a photographer, but instead she signs the work as an artist. Maynard used her subject’s gender, age and symbols of class-based sophistication as a backdrop and canvas to draw a line connecting past artistic methods of recollection, as seen with the Swiss enamel, with the artistic and technical practice of photography. Maynard uses the brooch to bridge a conceptual relationship to photography but not to privilege the technology over the human hand. Instead she stages for the viewer a meeting between the artistry and status symbols of the past with the new techniques of portrait photography. In doing so she illustrates for us a lineage of remembering where the primary and central role belongs to the artist.

Works Cited

Salahub, Jennifer. 2012. “Hanna Maynard: Crafting Professional Identify.” In Rethinking Professionalism: Women and Art in Canada 1850-1970, edited by Kristina Huneault and Janice Anderson. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press. https://www-deslibris-ca.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ID/443449

Wikipedia. “Cabinet Card.” Accessed Dec 29, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cabinet_card