Many thanks to guest blogger Gabriella Cigarroa for contributing the below post! Gabriella is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and completed a professional experience with RBSC this summer.

From the Langmann Collection: Early 20th-Century Postcards Depicting Disasters and Accidents

This summer, I completed a Professional Experience at RBSC to assist with cataloguing unprocessed materials. I wanted to work with RBSC to learn more about how special collections document the community they serve. At first, I catalogued posters, broadsides, prints, and other kinds of items that documented B.C. history. A few weeks in, I was offered another project: writing about the Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. I worked specifically with the digital collection, a subset of the larger collection of more than 18,000 photographs that documents B.C. from the 1850s to 1970s.

In the Langmann collection, I encountered many postcards whose picture sides captured disasters and accidents. Postcards today generally feature scenes more appealing to tourists, often picturesque landscapes or buildings. While postcards of this type are present in the Langmann collection, there are also plenty with more unexpected subjects—including that of disasters and accidents. Why was this subject matter chosen as a relatively common subject of photography for postcards, to be sent as correspondence? And what about the format of a postcard is different today from a hundred years ago such that these postcards’ imagery surprised me?

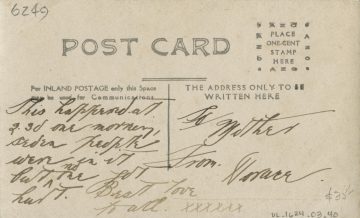

Two postcards first caught my eye, illustrating the contrast between friendly personal correspondence and an image of a disaster or accident. The first, titled A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. car, Vancouver, B.C., features a photograph of a streetcar crash’s aftermath. The photographer is positioned inside the wrecked building, framing the streetcar with the storefront’s windows. Inside the building, debris is piled haphazardly on the windowsill. A group of children smiles, looking in the window of the presumed storefront, maybe even noticing the photographer inside. On the postcard’s back, the sender, Horace, writes to his mother: “This happened at 2.30 one morning, seven people were in it but no one got hurt. Best love to all.” I questioned, why did Horace send this photo and information to his mother?

- Barrowclough, G. A. (1910). A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. car, Vancouver, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0040) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361427

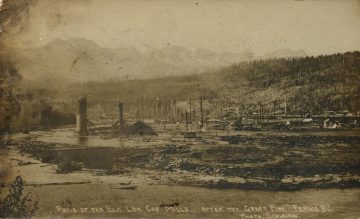

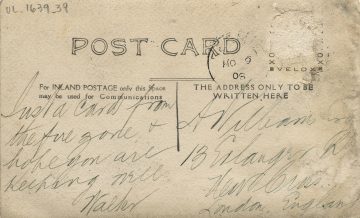

The other postcard presents a picture taken after a fire in Fernie, B.C. In the photographed landscape, few buildings remain intact. Some smokestacks rise from the rubble, while burnt-out husks of trees stretch into the distance. I was struck by the casual language on the postcard’s back, as a man named Walter writes to someone in England: “Just a card from the fire zone + hope you are keeping well.”

- Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

I took a step back to consider the context of these postcards’ creation. As briefly discussed earlier, the purpose of a postcard today is different from that of the other materials I catalogued this summer. The materials outside of the Langmann collection—posters, prints, broadsides, and so forth—were generally created with a broad audience in mind. Postcards, however, are often for personal correspondence. Today, this difference in audience would typically mean a major difference in subject matter. Usually, a person today would want to show a loved one picturesque landscapes, not tragic news relevant primarily to their neighbouring residents. Was this different a hundred years ago?

- Armitage, S. J. (1908). Fernie, B.C., After the Fire of Aug. 1st. 1908 (UL_1639_0003) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371490

- Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

The postcards I selected are roughly from between 1905-1915. It turns out that this period was in the midst of a postcard craze, in which an estimated one billion postcards were created each year in North America (Photo Postcards, n.d.). About ten percent of these postcards were real-photo postcards—silver-gelatin photographs made either as one-offs or in small numbers. In 1903, Kodak had created the A3 camera and an accompanying photograph development kit that allowed anyone to produce a silver-gelatin photograph on postcard paper (Photo Postcards, n.d.). This technological development that allowed increasingly portable and cheap photography, alongside an inexpensive postal system, encouraged layperson photographers to ply their trade. This real-photo postcard craze lasted from 1905 to 1930, although the process was still used into the 1950s (Photo Postcards, n.d.), permitting anyone with such a camera to make a postcard.

Most photo postcards in the Langmann collection are taken by photographic printing companies or unknown photographers. However, the photo postcards I found depicting disasters and accidents were mostly created by individual photographers or unknown individuals. Since anyone with a postcard camera could take postcard photos, the postcards without credit on them could be by anyone, including their senders. Alongside individuals taking their own photos, the postcard camera allowed for a rise in amateur photographers and photography studios.

The photo postcards in the Langmann collection featuring disasters and accidents seem to be created by a few identifiable photographers: Joseph Frederick Spalding, Rosetti Studios, and George Alfred Barrowclough. All three photographed more than the disasters and accidents I initially encountered. Joseph F. Spalding is known for documenting the history of Fernie, B.C., especially the reconstruction after the fire in 1908 (Joseph Frederick Spalding, 2006). Rosetti Studios was run by Lionel Haweis, who is best known for his series of photographs recording the development of Stanley Park (Rosetti Studios – Stanley Park Collection, n.d.). Lastly, Barrowclough is now seen as more of a photojournalist (for a more in-depth discussion of Barrowclough’s work, see my colleague Brandon Leung’s blog post). These photographers chose what they thought should be documented history, and even reproduced as postcards. Whether amateur photographers, commercial studios, or people who happened to own a postcard camera, they all captured what they likely considered significant contemporary events.

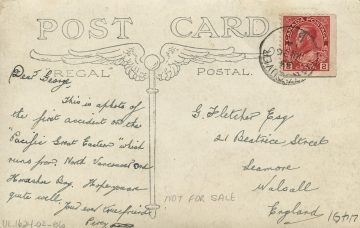

With some postcards, the disasters and accidents were likely considered one type of an event to record, and even to share with loved ones as news. For example, the postcard of the Fernie fire zone discussed earlier is one in a series documenting the town’s recovery and reconstruction (Joseph Frederick Spalding, 2006). Someone sending such postcards as correspondence could discuss the progress of Fernie’s recovery. In the case of other postcards, context concerning the senders’ intentions can be derived from reading the postcards’ letter component. We can look at [View of the Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.]. In the photograph, a train car lies on its side next to train tracks. A couple of people view the train car while others walk by. The back reads: “This is a photo of the first accident on the ‘Pacific Great Eastern’ which runs from North Vancouver and Horseshoe Bay.” The sender provides the context of the Pacific Great Eastern and describes its historical import as the railway’s first accident, marking it as a notable event.

- [unknown]. (1914). [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.] (UL_1624_02_0086) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0360930

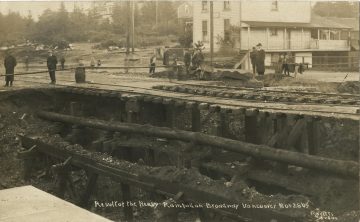

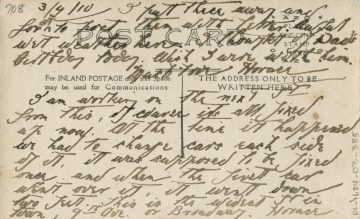

However, this kind of proto-, personal photojournalism is not the only reason for sending these types of postcards. Some postcards seem to be parts of bigger conversations held outside of a single letter. The postcard featuring the fire zone at Fernie is one example, as the recipient would be able to identify the unnamed “fire zone” mentioned in the letter without context from outside the single postcard. Another is the Result of the Heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09. The photograph displays a street in the aftermath of the rainfall, with a large pit and metal structures where the street should be. A set of tracks still runs over the pit. A few people on the side of the pit opposite the photographer look on. On the back of the postcard, a man named Horace writes, “This is next to where I’m working.” He describes not only the event of the crash, but how it interacts with other aspects of the city like the “awful wet weather,” as well as how the event affected his commute such that “[a]t the time it happened [he] had to change cars each side of it.” Horace incorporates these photos that record the city’s historic events into letters that detail his own personal life. Using these photo postcards, senders recorded and shared important events relevant to and connected with their own lives.

- Rosetti Studios. (1909). Result of heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09 (UL_1624_03_0335) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361442

So, does this answer why disasters and accidents were a relatively common depiction in photo postcards? Yes—photo postcards were a key type of personal correspondence. They were used not only to display pictures appealing to tourists and potential settlers, but to communicate about major events relevant to their senders’ lives. Created at the height of the early 20th-century photo postcard craze, they were likely part of ongoing conversations between parties. A single postcard may be a supplement to letters, other postcards, or even phone calls. This means that a postcard of a burnt-down Fernie, B.C. wouldn’t be out of the blue, but instead elaborating on previous conversations. These postcards were one aspect of a larger correspondence that encompassed different aspects of the senders’ lives. Senders could use these postcards to document landmark events in places close to them, as with the [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.]; as well as to weave historical events into records of their own lives, whether those events were some scheduled celebration, or an unexpected accident or disaster.

References

Armitage, S. J. (1908). Fernie, B.C., After the Fire of Aug. 1st. 1908 (UL_1639_0003) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371490

Barrowclough, G. A. (1910). A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. Car, Vancouver, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0040) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361427

Joseph Frederick Spalding—Photographer – Tourist – Visionary : Summary. (2006). University of Victoria Cultural Property Community Research Collaborative. https://maltwood.uvic.ca/cura/projects/joseph_spalding/home.html

Leung, B. (2020, December 18). Exploring Barrowclough’s Postcards. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections. https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/2020/12/18/the-postcards-of-george-alfred-barrowclough/

Photo Postcards. (n.d.). University of Calgary Archives and Special Collections. https://asc.ucalgary.ca/photohistory/photo-postcards/

Rosetti Studios. (1909). Result of heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09 (UL_1624_03_0335) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361442

Rosetti Studios—Stanley Park Collection. (n.d.). University of British Columbia Library Open Collections. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/rosetti

Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

[unknown]. (1908). Fernie after the fire (UL_1638_0051) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361853

[unknown]. (1914). [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.] (UL_1624_02_0086) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0360930