A new exhibition, The Road to the OED: A History of English-Language Dictionaries, is now up in Rare Books and Special Collections!

This exhibition features work done by seven students from the course English 320: History of the English Language. For this class, Professor Laurel Brinton asked each student to select one dictionary from the H. Rocke Robertson Collection of Dictionaries, to research the author of the dictionary, and to report on the features of the dictionary in the context of the history of English lexicography–the activity or occupation of compiling dictionaries. We were delighted to include these reports and the dictionaries that inspired them in in our exhibition, and each week, we will be posting one student report and photos of the dictionary on our blog. We hope this inspires you to stop by to see the rest of the exhibition, or simply to take a little extra time to appreciate the humble dictionary the next time you look up a word!

You can visit the exhibition at Rare Books and Special Collections on the first floor of the Irving K. Barber Learning Center from 10 a.m.-4 p.m., Monday-Friday, and from 12-5 p.m. on Saturdays until December 24, 2013.

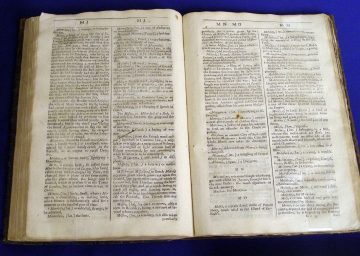

Phillips, Edward. The New World of English Words: or, A General Dictionary. London: Printed by E. Tyler, for Nath. Brooke at the Sign of the Angel in Cornhill, 1658. PE25 .R62 V. 260

First published in 1658, Edward Phillips’ New World of English Words has the distinction of being the first folio English dictionary. In terms of content, it is firmly placed in the tradition of dictionaries of “hard words” initiated with Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall of 1604. As the title states, the work contains “the Interpretations of such hard words as are derived from other Languages; whether Hebrew, Arabick, Syriack, Greek, Latin, Italian, French, Spanish, British, Dutch, Saxon, &c. their Etymologies and perfect Definitions.” Phillips then goes on to offer a long list of specialized disciplines and sciences whose terms will be explained in the dictionary, including “Theologie,” “Physiognomy,” “Jewelling,” and “Husbandry,” and adds that the reader will also find “The significations of Proper Names, Mythology, and Poetical Fictions, Historical Relations, Geographical Descriptions of most Countries and Cities of the World.” As with all dictionaries of this kind, the main difference between the New World and modern lexicographical works is the conspicuous absence of common, everyday words. This was standard practice at the time, and would only begin to change with the publication of Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755.

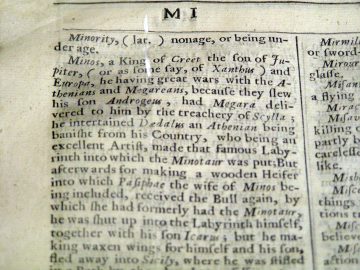

Entries in the New World are extremely straightforward: the headword appears in italics, and the definition follows. What Phillips calls the “etymology” is a parenthetical indication of the language of origin which occurs between the headword and the definition in most but not all entries. The style and the content of the definitions themselves are fairly inconsistent. A definition can range from one word, like “exalted” for Mary, to a list of synonyms, like “weaknesse, indisposednesse” for Infirmity, to a short explanation, like “a calling aside, a drawing apart” for Sevocation, to what amount to brief encyclopaedic entries, like that for Minos. If we compare these entries with those in modern dictionaries we notice again that much is lacking. Phillips does not provide a pronunciation guide, for example, a feature which is particularly missed in a dictionary composed almost exclusively of rare words, usually of foreign origin. Neither is the part of speech indicated, though most words—again, as with most “hard words” dictionaries—are either nouns or verbs. The etymological aspect, as has been said, is extremely deficient, and, in fact, does not even meet the standard set by Phillips’ own definition of the word as “a true derivation of words from their first Original.” Lastly, as we would expect, Phillips does not make use of illustrative quotations, nor does he seem at all to be interested in usage, as evidenced by the fact that he makes use of a small group of “learned Gentlemen and Artists,” which he lists at the beginning of the work, as sole authorities for his definitions.

Though the New World was a popular and successful dictionary, it is unlikely that it made any impact on the development of the discipline of lexicography, save perhaps as being part of that tradition which writers such as Johnson were trying to improve upon. Phillips’ was an unoriginal work, both in design and in content—he plagiarized a considerable number of his definitions from Thomas Blount’s earlier Glossographia—and it is safe to say that it was partly with the New World in mind that the Earl of Chesterfield declared in 1754 that “our dictionaries at present [are] more properly what our neighbours the Dutch and the German call theirs, word-books, than dictionaries in the superior sense of that title.”

— Javier Ibáñez (English 320: History of the English Language, 2012-2013)