Many thanks to guest blogger James Goldie for contributing the below post! James is a graduate student at UBC’s iSchool (School of Library, Archival and Information Studies) and is currently working as a student archivist with Rare Books and Special Collections.

“They also serve:” A. Alexis Alvey and the navy’s first female service members

Unit Officer A. Alexis Alvey of the W.R.C.N.S.

Her mother calls her “the Canadian lieutenant” and the girls in the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service call her “Chiefie”…

So begins a 1943 Royal Canadian Navy press release announcing the promotion of Lieutenant Amelia Alexis Alvey to Unit Officer at H.M.C.S. Stadacona, a rank equivalent to that of an army captain. This new position – granted just a year after she first enlisted – meant Alvey was in charge of more than 1,100 Halifax-based service members from the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS), known as Wrens. More than a third of all Wrens were stationed at H.M.C.S. Stadacona in Halifax.

Alvey (who went by A. Alexis Alvey) was born November 22, 1903 in Seattle, Washington. After completing her undergraduate studies in New York, Alvey studied science at McMaster University (1932-1933) and went on to work as chief photographic technician at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine. It was during this period she gained Canadian citizenship. After the outbreak of World War II, Alvey helped organize the businesswomen’s company of the Toronto Red Cross Transport Corps and commanded it for two years. She had also served as lecturer to the entire Transport Corps for Military Law, Map Reading, and Military and Naval Insignia.

Recruitment advertisements ran in magazines throughout Canada from 1942-1944, reminding readers that women could now serve in the navy as part of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service.

Men Can’t Do It Alone

In 1942, top brass in the Canadian navy realized they could not solely rely on men in their fight against Hitler’s forces. They contacted the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) in London requesting assistance in the formation of a Canadian counterpart. “Please send us a Mother Wren,” they said, according to Alvey. Those “mother wrens” were Joan Carpenter and Dorothy Isherwood, who came to Canada and established the WRCNS later that year. Alvey was among the first to enlist.

Until then, the Canadian navy had been an all-male service. As one member wrote in 1943: until the establishment of the WRCNS, “ships and shore establishments alike were manned by men, and knitting seamen’s stockings, or collecting magazines, games and special parcels for ships’ crews at sea was about the limit of any contribution made by women.”

Women were not permitted to serve in combat roles, however, they took over the navy’s on-land operations, which freed up male service members to join battles at sea. The Wrens worked as signallers, wireless-telegraphers, writers, information and intelligence workers, postal clerks, research assistants, cooks, stewards, wardroom attendants, laundry assistants, and more.

Rising Through The Ranks

A. Alexis Alvey (far right) with fellow “Wrens” at the W.R.C.N.S. training centre in Galt, Ontario.

In her first year with the WRCNS Alvey was appointed acting Chief Petty Officer Master-at-Arms. Her other assignments included duty as Deputy Unit Officer H.M.C.S. Bytown (Ottawa), duty with the Commanding Officer Pacific Coast H.M.C.S. Burrard (Vancouver), assignment as Unit Officer, Lieutenant H.M.C.S. Bytown, and finally Unit Officer to H.M.C.S. Stadacona (Halifax). She was responsible for training and running practice drills, developing policies, and meeting with officers from ships that arrived in Halifax.

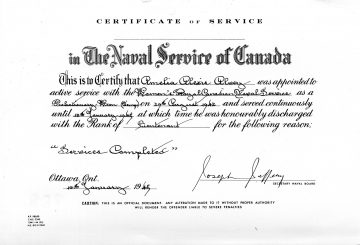

She served with the WRCNS from August 1942 to January 1945.

The A. Alexis Alvey Fonds

After the war, Alvey returned to her home city of Seattle where she worked as a librarian at the University of Washington. However, she never forgot her time with the WRCNS. For the rest of her life, Alvey organized and attended Wrens reunions, she wrote articles and histories about the service, and collected all manner of documents, memorabilia, and ephemera related to the “The Women’s Navy” as it was sometimes called.

The Royal Canadian Navy’s certificates of service were designed with only male service members in mind.

These records along with Alvey’s personal papers and an extensive collection of photographs are housed at UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections and are available for research.

The materials that make up the A. Alexis Alvey fonds express the profound sense of pride shared by Alvey and her fellow Wrens with respect to their years of military service. An essay commemorating the WRCNS silver anniversary by Isabelle NcNair (née Archer) captures this pride. In it, a grandmother tells her granddaughter the story of the Wrens. “But Grannie, I thought Grandad won the war,” asks the child. “No dear,” responds her elder, “I did.”