Show and Tell: Selections from our Personal Archives and Libraries

How we remember, and what we hold dear, differs from person to person. All of us have personal archives we keep to preserve memories that are precious, that document our families, our histories and record important events. It could be a simple piece of ephemera we love and cannot part with (a ticket stub from our first concert, for example), or photographs of ancestors that offer clues to our origins, or anything we have set aside and saved for a myriad reasons. Similarly, our personal libraries hold volumes that have emotional value to us, not just for the words contained in it, but as a reflection of a time in our lives, we found them particularly relevant. This could be the first book of poetry that made us fall in love with verse, or the dog-eared copy of a classic novel that led us to our current passion for libraries and library work. This blog series explores selections from the personal libraries and archives of members of the Rare Books and Special Collections team, and other colleagues from UBC Library and beyond. We hope our stories will help you reflect on what is meaningful at this time in your, and in our, collective histories.

— Krisztina Laszlo, Archivist

Ashlynn Prasad, Archives and Reference Assistant, RBSC

As a young professional acquainting myself with archives, it actually took me a long time to understand the ways in which the archival world had already touched my personal life. I started working in an archives at the age of 18, at which point older cousins of mine had already been entering what I would come to understand as archival spaces for years. They were undertaking a genealogical research project that would hopefully uncover who we were, who our ancestors had been, and where we all came from.

The information that had travelled down through the generations about our family history was minimal at best: we knew that my great-grandparents’ generation had migrated to Fiji from India in the late 1800s. We knew that they had been indentured labourers for the British Empire, who held control of India at that time and were looking for a labour force to work the land in Fiji, another place they had colonized. The list of things we didn’t know was much longer: the names of our ancestors who had originally migrated, the name of the ship they had come over on, where in India they had come from, why they had chosen to leave their home for a difficult life of farming on a remote island nation that was fraught with sometimes violent tension between the colonizers and the indigenous community – and the list went on. Theories abounded in our family, particularly over the latter question. Our theories were mostly romanticized stories that we told ourselves, about ancestors who had fled India, perhaps to escape arranged marriages, with a secret lover, in hopes for more freedom in Fiji.

Research on the part of my cousins and other Indo-Fijian scholars has provided us with a vision of the past that is slightly less rosy. In recent years, the term “indentured labour” has come to be understood as little better than debt slavery. And while we had assumed that our lack of information about our ancestors was due to an intentional effort on their part to hide information about themselves, it now appears that the true reason is due largely to the poor record-keeping practices of the British.

A further complicating factor has been the fact that naming conventions among the Indo-Fijian community are different than what we in western society are accustomed to, and what the British record keepers would have expected. In Indo-Fijian society, there is no such thing as a family name. Siblings will often all have the same last name, but it won’t be the same name as their parents. Because of this, it is nearly impossible to track lineage through a family name. And because the British record keepers didn’t understand this, there is nothing in the records of Indo-Fijian immigrants to tie generations of one family together.

This is what has made the search for our family’s origins so challenging. The search has been a piecemeal collaboration of whatever information we can find. It has included scraps of records that we were able to find using the information we already had, such as the birth certificate of my maternal grandfather pictured above.

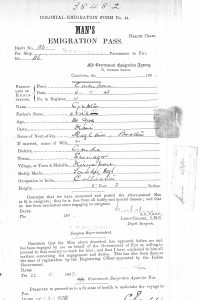

It has also included records that were painstakingly dug up from the notoriously restrictive Fiji National Archives. In one instance, my cousin began undertaking research in the archives, equipped with the name of my mother’s paternal grandfather – he had dropped his first and middle names and simply went by his last name, “Gupta” (written by the British as “Guptar”). My cousin was able to narrow down his search to two possible records, but reached an impasse because he had no further information about our great-grandfather. The only way he was ever able to figure it out was by calling upon the help of the rest of the family: my mother, her ten siblings, and the twenty-eight cousins in my generation. It turned out that, years before, a great-aunt had visited my parents, had told a few stories and happened to mention the name of a village in India, which my mother had happened to make a note of. That piece of information allowed my cousin to narrow down his search to the record you see here: my great-grandfather’s emigration pass, which tells us his father’s name, his age when he migrated, his brother’s name, the specific area in India he came from, his occupation, and – perhaps most interestingly – his caste.

In some ways, the moral of the story had been in front of me for years before I even knew what an archives was: good record keeping matters.