Many thanks to guest blogger, Barbara Towell, for contributing the below post! Barbara is University Archives’ E-Records Manager and an enthusiastic collector of antiques. This is the first post in her occasional series on jewellery pieces worn in historical cabinet card portraits.

Popular complications: telling the time

I can pinpoint the moment my love-affair with the past began. It was the day a trunk was moved from my grandmother’s house in New Westminster to our basement in Burnaby. The chest was the curved-top variety lined with cedar with a large bottom drawer. How long it sat in the basement before I uncovered its secrets, I cannot tell you, likely hours, not days. The weight of the lid…the squeak of the hinges…the smell of the cedar; that was the moment.

Item zero: watch found in cedar trunk. Fitted case not original to the watch. Image credit: Barbara Towell

The bottom drawer was where the treasures lay. The passage of time had dried out the wood, to open it I had to pull one side of the drawer then the other inch by inch. When I got it open, I saw hundreds of photographs. I expected to recognise my grandparents, my father, or my uncles, but in photo after photo I did not know a single person. Over the days, months and years I made my acquaintance with each and every face. Sitting in the basement studying the faces stored in the bottom drawer was a favourite childhood pastime. But the photographs were not all the trunk contained, there was another item hidden amongst the trunk’s contents: an old watch.

Sometimes I am asked about the first item in my collection of old things. Perhaps because I can recall the particular transaction so clearly, I have always answered that it was a Czechoslovakian glass and brass necklace from the 1920s bought for $12.00 at a shop called the Blue Heron. It is only in writing this blog that I realize the watch uncovered in the cedar chest that day when I was 11 years old was actually item zero.

I tell you this story because old photographs and jewellery introduces a series of blog posts I am writing looking at cabinet card portraits of women and the jewellery they wore. In these examples the ornaments displayed hold a central role in the images’ composition and meaning.

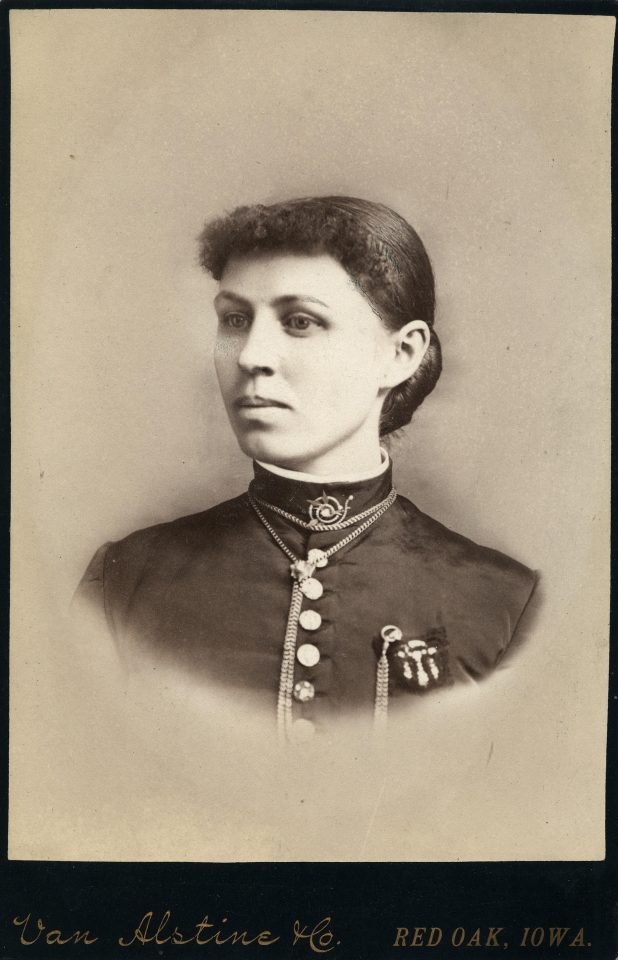

Originally shot by Van Alstine photographers Red Oak, Iowa, the photo is part of the Uno Langmann and Family Collection of British Columbia Photographs. Cabinet cards gained popularity in the 1870s and 1880s and were an accepted and affordable method of portraiture. One can locate many such examples in this period of (primarily white) women in black clothes wearing a watch on a long chain. Dr. Annie Rudd describes this kind of portraiture as the social media of the 19th Century (Rudd, 2015). Rudd sees the carte de visite, a smaller precursor to the cabinet card, as a “socially sanctioned and standardized mode of self-presentation” (Rudd, 2015) and because both the carte de visite and the cabinet card were designed to be shared they helped shape cultural standards through their distribution.All we can see of the woman’s outfit is a black button-down bodice and an odd-looking pocket sewed onto the front of the outfit. The pocket has not been sewn on straight, the right side is higher than the left. One cannot mistake the quality of the material and perfectly close fit of her bodice so why is the pocket sewed on in this way? Part of the answer is that the pocket holds a watch. Watches were very popular all through the 19th Century and women in the last quarter wore their watches one of three ways:

- tucked into a belt or a fit-for-purpose pocket at or near the waist;

- at the bodice hanging from a brooch watch chatelaine; or

- as we see in this photo tucked into a crochet or lace pocket angled with the right side higher than the left.

But why? The answer is for practical ease of access. The subject is right-handed and it is simpler for the right hand to take the watch out of the pocket on the left if the pocket is slightly angled. It would stand out more to viewers contemporary with the period if the crocheted pocket wasn’t angled. In all three cases the watch hung from a long chain called a muff or guard chain which was typically 154.4 centimetres in length (Cummings, p. 95).

The guard chain in the Van Alstine cabinet card is doubled under the chin drawing the viewer’s eye toward the face. Given this is a portrait the brooch and chain’s placement near the throat makes sense; it emphasizes the subject. Her appearance is not all we are meant to see; the draping of the chain draws the viewer’s eye to the crocheted pocket. The angle and texture of the pocket emphasizes the timepiece within suggesting action, functionality and matter-of-fact practicality on the one hand, and a modicum of affluent comfort on the other. If highlighting the face is the point of the portrait, the watch functions as a balancing counterpoint. Everything included in the cabinet card’s field of view was made by choice. The passage of time has undermined the clarity of photograph’s message, but her outfit and the simple yet meticulous construction of the image communicates middle class propriety and tasteful prosperity.

Cabinet cards typically include an advertising block containing the name and location of the business; indeed, advertising was one of the main objectives of the medium. They also promote a “carefully calibrated self-presentation” of the subject (Rudd, 2015). The assembly of clothes, hair and pocket watch work together as kind of visual shorthand for respectable middle-class conventionality. The actual material conditions in which this woman lived are unknown to us, but through the composition of the photograph we are led to believe that she has a comfortable life with places to be and appointments to keep!

Works Cited

Rudd, Annie. 2015. “Public Faces: Photography as Social Media in the 19th Century.” The International Center of Photography, Aug. 27, 2015. Accessed Dec. 26, 2020. https://www.icp.org/perspective/public-faces-photography-as-social-media-in-the-19th-century

Cummins, Genevieve. 2010. How the Watch was Worn: A Fashion for 500 Years. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club Publishers.