Canada’s Silk Trains

Posted on April 9, 2025 @11:34 am by Chelsea Shriver

“Nothing material, not even the mail, moves across oceans and continents with the speed of silk”

– George Marvin (The Sunday Province, 10 February, 1929)

We are delighted to announce a new display– Canada’s Silk Trains – which tells the story of the fast-paced silk train era. From the time that the first 65 packages of silk were unloaded in Vancouver on June 13, 1897, the race was on to find the fastest way to transport this valuable cargo across Canada and on to the National Silk Exchange in New York.

Between the late 1880s to the mid-1930s, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and later the Canadian National Railway, competed against time, the elements, and each other to transport silk to eastern markets. Insurance rates for silk were charged by the hour, incentivizing the rail companies to pursue faster and faster transportation times.

Despite the high speeds of the silk trains, there were very few accidents. The most well-known incident occurred on September 21, 1927, when a silk train derailed just beyond Hope, British Columbia, sending 4,500 bales of silk into the Fraser River. This accident was reported in newspapers at the time, and later provided the inspiration for the picture book Emma and the Silk Train. Images of the accident are not common, and so we were excited to identify two confirmed photographs (and one suspected photograph) of the crash in the newly available Price family collection. The display features books, photographs, and newspaper articles from across UBC Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections.

Canada’s Silk Trains is on display in the Rare Books and Special Collections satellite reading room on level 1 of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre and can be viewed Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. through July 4, 2025. For more information, please contact Rare Books and Special Collections at (604) 822-2521 or rare.books@ubc.ca.

References

Lawson, J. (1997). Emma and the silk train. (Mombourquette, P. Illus.). Kids Can Press (PZ4.9.L397 Em 1997).

Marvin, G. (1929, February 10). Fast as silk? [Microfilm of The Sunday Province, Vancouver, p.3]. https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/february-10-1929-page-43- 56/docview/2368257290/se-2

No CommentsPosted in Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Research and learning | Tagged with

Leon J. Eekman Materials

Posted on April 1, 2025 @1:35 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is part of RBSC’s blog series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

While the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung collection is best known for its large Canadian Pacific and Chinese immigration holdings, it also contains a wide variety of miscellaneous photos and materials from across Western Canada and Pacific Northwest. These can often allow us insight into lives that indicate the differences of experience between immigrant communities in BC, particularly between European colonists and other groups. Today we will be discussing the life of a Belgian-Canadian whose materials are found in the Chung Collection, Leon Eekman.

[Portrait of Leo J. Eekman] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11113. Chung Collection. 1909. B&W Photograph

Leon (Leondart, Leendert, Leonard) John (Jan, Jean, Jeens) Eekman was born on December 12, 1880, in Brussels Belgium, likely of Flemish background. He was from a large middle-class family with at least four brothers and one sister. When he was young he served as a sergeant in the infantry stationed in Liège, Belgium, before arriving in Canada around 1905, first to Manitoba and then settling in Victoria, British Columbia. A well-educated man with fluency in English, French, German, Flemish, conversational Dutch, and Walloon, Eekman soon found work as a language tutor. As a result he quickly became acquainted with colonial society, including the family of Chinese merchant Loo Gee Wing, subject of a previous blog. By 1908 he was also working as a surveyor and draftsman, well-established enough to employ a Chinese domestic servant, Ah Guan 關亞均, which was common among the colonial well-to-do.

This young man was a likely cook, gardener, and/or servant to Eekman or Holdcroft Family [Portrait of 關亞均, Ah Gwan] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11088. Chung Collection. 1908. B&W Photograph

His movements over the next few years suggest a complex transatlantic life; in 1909, he returned to Europe via New York City aboard the SS Oceanic, to attend the 1910 Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Bruxelles re-entering Canada in September 1910. He was at that point recorded as a tourist with no stated intention of permanent residence. Despite this, he made his way back to Victoria, where he had lived before. The differences between his easy crossing of borders and those of Chinese Canadians during a time of tightening exclusion are a noteworthy comparison here.

Front of Leon J Eekman’s 1910 Brussels International Exposition Pass. [Exposition Universelle & Internationale de Bruxelles 1910] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11108. Chung Collection. 1910. B&W Photograph on board

Shortly after his return, Eekman married Marion Holdcroft on November 10, 1910, in Victoria, after courting her in previous years. The wedding took place at the home of his in-laws, and through this union, he became connected to the Holdcroft family, a well-respected colonial lineage with English roots. Marion’s father, John Holdcroft, was the Assistant Surveyor of the City of Victoria, a role that Leon himself would later hold. Marion’s maternal relatives had been English merchants in Brussels, later starting a toy company. In their early years of marriage, Leon and Marion lived with her parents at 1268 Walnut Street, and Leon continued his work as a language tutor and surveyor. Around 1912, he became a naturalized British subject, further solidifying his ties to Canada. During this period the ability of Asian diaspora communities in BC to naturalize had been slowly restricted, likewise showing a diverging experience of legal belonging.

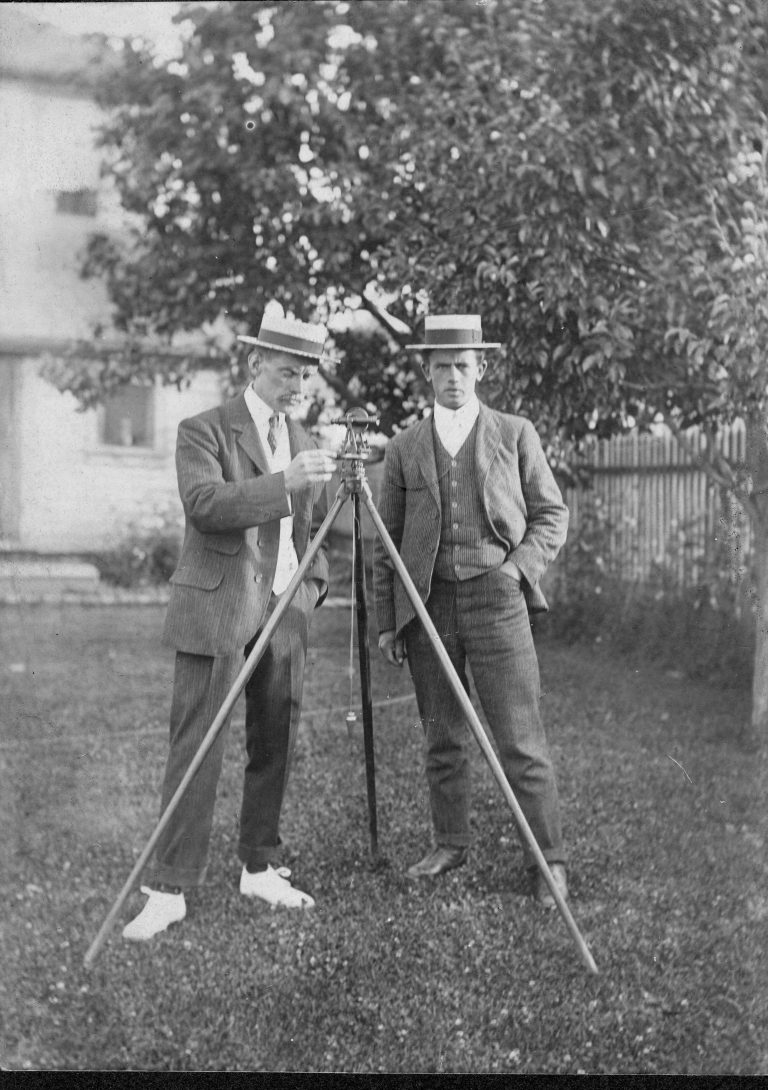

Leon (left) and likely Walter (right) Eekman surveying. [Leo J. Eekman] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11078. Chung Collection. 16 Jul. 1907. B&W Photograph

When World War I broke out, Leon enlisted with the Gordon Highlanders (50th Reg.) He later served in the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC), working under Colonel Murray McLaren at a field hospital in Étaples, France. His brother, Arie Eekman, also served in the same conflict in the Netherlands Army as a Militia Sergeant of the First Corp. Motor Service in Delft. Leon’s role involved the grueling and dangerous task of transporting wounded soldiers from the battlefield to medical facilities. His service was not without hardship; in October 1915, he contracted tuberculosis, which would shape the remainder of his service.

Leon Eekman in uniform, Nov 1914. [Portrait of Leo J. Eekman] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11080. Chung Collection. 21 Nov . 1914. B&W Photographic Postcard

Fearing anti-German sentiment in Victoria impacting his family due to his surname, Eekman wrote a public letter to the Victoria Daily Times from the front in June 1915, proclaiming his British loyalty and that of his family. By May 1916, his health had deteriorated to the point that he was medically discharged and sent to the Esquimalt Convalescent Home, followed by six months at the Tranquille Sanatorium. Still wanting to serve, Eekman was frustrated in his attempt to serve as a translator; he suspected discrimination due to his German-sounding name. His military discharge became permanent in July 1918, and he returned to civilian life in Victoria.

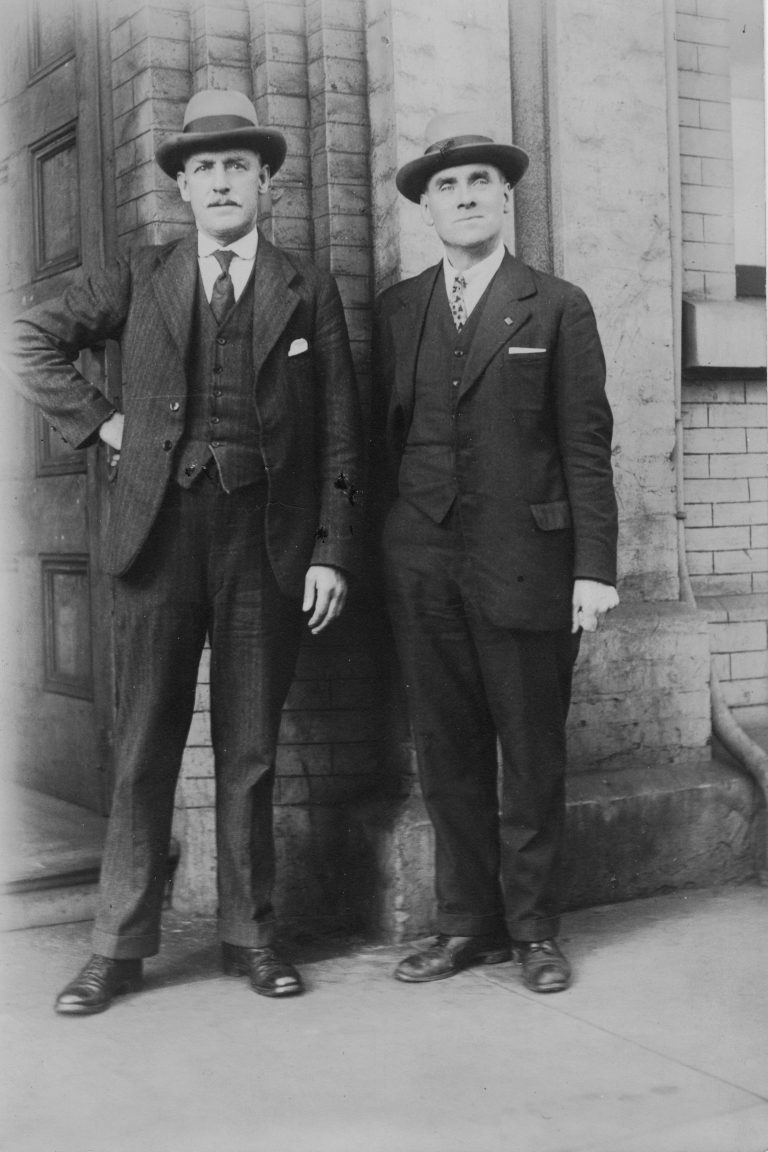

Leon (right) and colleague in front of Victoria City Hall. [Building and plumbing inspector and assistant building and plumbing inspector] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11092. Chung Collection. 1930. B&W Photograph

After the war, the Eekman family settled at 1303 Hillside Avenue. Leon petitioned the city to restore his pre-war position in the survey department, which he had left upon enlisting. This is a position that would have been excluded to non-whites by statute during this period. Over time, he became a provincial draftsman and later served as the Assistant Building Inspector for the City of Victoria. Beyond his professional life, he was deeply involved in religious and civic activities. A passionate evangelical Christian, he was active in the Shantymen’s Association, ministering to working men in remote (particularly mountain and coastal areas) of British Columbia. His religious fervor extended into his participation in the Canadian Protestant League, a controversial anti-Catholic organization. He frequently wrote newspaper columns and letters to the editor, engaging in heated theological debates, often garnering response letters about his all-to-frequent contributions.

Leon (2nd from left) and other mission workers of the Shantyman’s Association, Lake Cowichan BC, 1925. [Ye must be born again truck] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11095. Chung Collection. 1925. B&W Photograph

During World War II, Eekman was appointed Acting Belgian Consul for Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii, where he assisted in the registration and conscription of Belgian diaspora men for the war effort. He requested every Belgian-Canadian house fly the Belgian and British flag to show loyalty. In April 1946, after 40 years of service with the city, he retired although his diplomatic work continued until 1947. He was a part of the welcome committee for Princess Juliana of the Netherlands when she visited Victoria, and in 1948 he was awarded the Order of Leopold II for his service to Belgium. In his later years, he continued to write emotional public letters and became a vocal critic of government policies, particularly opposing CMHC’s affordable housing initiatives in Saanich, which he felt discriminated against taxpayers. He also spoke out against age discrimination in the workforce.

The Eekman Family home served as Belgian Consulate during WWII. They displayed the two flags as Eekman had requested all Belgian Nationals do in his consular district. [Consulat de Belgique = Belgian Consulate] / L. J. Eekman. RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11090. Chung Collection. 1944. B&W Photograph

In 1949, Leon made a four-month trip to Europe, likely his first since World War I, visiting relatives in England and the Continent. By 1950, he had resumed his role as Honorary Belgian Consul for Vancouver Island. He remained an outspoken and controversial figure in the community until his death in 1954. His obituary in the Times Colonist on September 25, 1954, detailed his lifetime of contributions to Victoria and beyond. His memory lived on through his two surviving children, including Walter Gordon Eekman (born in 1912), continuing the family’s presence in Victoria for generations to come.

In 2005 some personal materials of Leon Eekman were purchased from Wells Books in Victoria, before being donated to the University of Manitoba Archives in 2015. They offer insight into how Dr. Wallace Chung may have acquired these materials.

While they can often challenge us, stories like that of the Eekman family allow us to view the range of experiences of BC residents across time. We invite you to engage with the digitized and physical materials of the Chung Collection and other holdings at Rare Books and Special Collections that may have relevance to genealogical or historical research.

Sources

University of Manitoba Archives, Leon J Eekman Fonds. https://umlarchives.lib.umanitoba.ca/leon-john-eekman-fonds

Leon John Eekman. Personnel Records of the First World War. Library and Archives Canada. RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 2848 – 49. Item 374921. Canadian Expeditionary Forces (CEF)

Victoria Daily Times and Victoria Times Colonist, Newspapers.com

No CommentsPosted in Chung, Chung | Lind Gallery, Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Highlights, Immigration and Settlement, Research and learning | Tagged with BC History, Belgian-Canadians, Chung Collection, Chung Lind Gallery, Universal Expositions, Veterans, Victoria, World War One

Winter weather closure

Posted on February 3, 2025 @10:06 pm by Chelsea Shriver

![[Two women and a man holding walking sticks on snow]](https://library-rbsc-2017.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2016/12/snow-website-360x300.jpg)

[Two women and a man holding walking sticks on snow]. CC-PH-04319.

We apologize for any inconvenience and hope you are all staying safe and warm!

No CommentsPosted in News, Services | Tagged with

Chinese New Year and “the Chinese Lily.”

Posted on January 29, 2025 @4:52 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is a special edition of RBSC’s series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

Happy Lunar New Year from the Chung Lind Gallery and the whole UBC Rare Books and Special Collections team! We wish everyone safe, healthy, and an auspicious year of the wood snake.

Chinese New Year celebrations have been a part of BC’s history and culture for at least over 150 years, enlivening both big cities and small towns with the sound of firecrackers, the rainbow colors of parades, bright red decorations, and the scent of special foods wafting in the air. There are many traditions and customs that vary both from region to region in China, but also family to family. Of the many traditions brought by the older waves of migration (lo wah kieu 老華僑), the visiting of flower markets (花市) and the cultivation of special lucky plants in the heart of the winter was and is cherished. One of the most prized plants was the Chinese Lily (水仙花), which is actually not a lily at all! This plant will be the topic of our celebratory blog today.

New Year’s Day in San Francisco’s Chinatown. 1881. Theodore Wores, artist. Oil paint on canvas. Collection of Oakland Museum of California. Gift of Dr. A. Jess Shenon.

Known by many names, including the bunch-flowered daffodil, Chinese sacred lily, cream narcissus, and joss flower, Narcissus Tazetta was brought to North America by Chinese workers during the California Gold Rush. The plant itself is native to the Mediterranean and was brought to China along the Silk Road before the Tang Dynasty. The early Chinese migrants to North American called it Sui Sin Fa “Water Fairy Flower,” a name likely derived from the Greek myth of Narcissus, which gave the flower its English name. Bulbs of the beautiful, highly fragrant flower were grown in Zhangzhou 漳州 Fujian 福建 and exported to Chinese communities all around the world. From there, it can be found naturalized in the fields, abandoned gardens, and Chinese cemeteries wherever Chinese were found in North America and wherever climate permits.

Yuen Fong Co. Ltd. 元豐公司. Nov 1962. “元蘴公司 = Yuen Fong co. ltd.” Iss 18. Vancouver, BC. UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-TX-307-1. Pg.1

The flower was prized because of its tight bunches of blooms and strong scent that grew when planted in shallow dishes in late October-Early November; they would ideally bloom right as Chinese New Year began. Multiple blooms from one bulb also had symbolism of plenty and abundance. They decorated homes, businesses, altars, and even photo studios, where they were used as a lucky prop for portraits sent back home during the New Year celebrations.[i]

In this formal portrait, likely the son of a wealthy merchant, notice the Chinese lilies to the side.

Unknown Photographer. 1910. “Chinese Boy.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00269 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0217964.

In BC, the flowers are found as early as the 1890s, though they most likely arrived earlier. In 1892, The Victoria Daily Times shared that the pet goat of a “well-known and justly popular saloon-keeper” had perished after eating a Chinese lily bulb gifted to the family by an employee for the new year.[ii] During the Chinese New Year season, Chinese servants would demand (and receive) vacation time, Chinese societies and social clubs would gather for banquets, and family businesses would give out gifts to partners, customers, and friends. The flowers and bulbs of the lily were very popular, leading to the following quote:

“Genii of the Water: All those who have visited the Chinese during the New Year festivities have noticed the sweet-scented flowers of the Chinese water lily, shin sin fa, water sprite flower, or water genii flower, which the Chinese always have in full bloom at their New Year. These, with branches of almond blossoms, pomelos and oranges, artificial flowers of paper and tinsel, a Chinese dragon embroidered in gold on a silken cloth, form the principal decorations of the Chinese New Year’s table, while upon it are Chinese candies, sugared fruits, laichis (Chinese nuts), and watermelon seeds, all in a lacquered box, called tsun hop, or complete box. These confections, and tea, wine and tobacco, are offered to all callers.”[iii]

By 1902, the plant was so popular among the non-Chinese community that a full page spread about how best to raise them was published in the Vancouver Daily News Advertiser. Ads for the bulbs were found prominently printed in the November issues of Chinatown Vancouver import-export businesses up to the 1970s, including the ad with instructions below.

Yuen Fat Wah Jung Co. 元發公司. Nov 1954. “Yuen Fat Wah Jung co. = 元發公司” Vancouver, BC. UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-TX-307-26

We wish you all a happy new year!

花開富貴 瑞氣呈祥

Further Reading

Hodgeson, Larry. “The Little Bulb That Conquered China” November 8 2017, Laidback Gardener Blog. https://laidbackgardener.blog/2017/11/08/the-little-bulb-that-conquered-china/

Footnotes

[i] Adams, John D. Chinese Victoria: A Long and Difficult Journey. Victoria, BC: Discover the Past, 2022.

[ii] The Victoria Daily Times Feb 15 1892 Pg.5

[iii] Vancouver Daily World, March 23 1901, Pg.2

No Comments

Posted in Chung, Chung | Lind Gallery, Collections, EarlyBC, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Highlights, Immigration and Settlement | Tagged with Chinese American History, Chinese Canadian History, Chinese New Year, Chung Lind Gallery, Plants

Stories of Chinese Sailors in Canada’s Maritime History

Posted on January 18, 2025 @3:07 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is long-form edition of RBSC’s blog series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

Early Entrances into Maritime Labor

The history of Chinese men working in the maritime industry in Canada stretches back to the initial arrival of the community to these shores in 1788. That year, 50 Chinese carpenters arrived in Yuquot as part of the Meares Expedition, hired for their skills in nautical repairs and as shipwrights.[1] As trans-Pacific connections developed between Asia, Oceania, and North America, Chinese sailors remained a part of the maritime workforce along the North American Pacific Coast. However, by the late 1800s they were more often assigned to the most grueling roles. Anglo-American culture had stereotyped Chinese as unreliable due to their lack of English, or because of their “superstitions” about weather or bad luck omens.[2]

Depicts six Chinese men in white jackets, possibly cooks and stewards, standing on the deck of the Iroquois. Unknown Photographer. 1920-1929. “Iroquois Crew.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00126. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0217393.

With steamship travel increasing in the 1880s, out-of-sight Chinese firemen (also called coal stokers or boilermen) worked in the engine rooms enduring oppressive heat, while cooks, stewards, and cabin boys toiled above in the crowded, tight kitchen galleys and passageways. On Canadian Pacific (CP) steamships, Union Steamship Company vessels, and other lines associated with Robert Dollar’s shipping empire, Chinese seamen were indispensable, but usually laboured in these segregated, unseen roles. Aboard the CP Empress liners, for example, they prepared their own Chinese meals in separate kitchens, resided in isolated quarters near the “Oriental Steerage Class” passengers, and were relegated to the back of the ship—both physically and metaphorically.[3]

Crew of an unknown vessel with one Chinese man. Unknown Photographer. 1910. “Crew Aboard a Steamship.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00128. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0217720.

Despite these hardships, Chinese mariners—from engine-room firemen to “tea boys”—built social and cultural connections across the British Empire, of which the BC coast was only one hub. Chinese sailors were also a common sight on Japanese imperial lines, such as Nippon Yusen Kaisha, that sailed for North America. While initially predominantly Cantonese, soon men from Zhejiang, Fujian, and other coastal areas joined crews around the world. This network of nautical workers also extended to the United States, which had its own Pacific ambitions and growing maritime empire.

Global Connections: From Liverpool to Hong Kong

As the 20th century dawned, the world of Chinese sailors continued to expand, linking British ports such as Liverpool to colonial hubs like Hong Kong. Liverpool’s docks, for example, became a focal point and safe haven for Chinese seamen post-World War I. The Blue Funnel Line, headquartered in Liverpool and one of the most active shipping companies in BC Chinese migrant traffic, hired many of these men to work onboard their vessels.[4]

Migration is never a simple equation; through shipping White settlers to North America, Blue Funnel brought Chinese sailors to the UK, fostering a small multicultural maritime community in Europe. Organizations such as the UK-based Dragons and Lions group now preserve the legacies of mixed-race descendants from this era, whose ancestors suffered separation when the British government turned against these Chinese sailors, even after some served during both World Wars.[5]

A group of Chinese seamen outside a Chinese hostel in Liverpool, sign on the left indicates it as a meeting place of the Tsung Tsin Society for Hakka speakers. Bert Hardy. May 1942. “Chinese Hostel, Liverpool.” Picture Post. 1136. Getty Images via The Guardian. Accessed Jan 16 2025.

Hong Kong, a key node in this global web, was where many Chinese mariners found work, retired, or kept families and businesses ashore. Others joined secret societies, mutual aid associations or sailors’ institutes.[6] Some even joined criminal gangs to make some money on the side through smuggling.[7] Here also, many were radicalized into political involvement.[8] The Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, recognizing the potential power of sailors to smuggle subversive documents world-wide, formed the Lianyi Society 聯義社, also known as the Chinese Seamen’s Association, in 1910.[9] It then coordinated the spread of revolutionary ideology, fundraised, and even transported contraband weapons across the often otherwise-exclusionary borders of empires.

The 1922 Hong Kong Seamen’s Strike demonstrated the immense collective power of Chinese laborers, disrupting service by most major Pacific shipping companies, like Canadian Pacific. The strike’s influence reached far beyond Asia, as British Columbia’s newspapers anxiously speculated about similar uprisings, creating ripples of fear in the Canadian trade establishment about potential labor unrest on their shores.[10] We will most likely return to this critical event in future blogs.

This photograph of staff from the 34th voyage of the Empress of Japan lists all the white members by name and title, from the Chief Steward to the hairdresser and assistant storekeeper. All the Chinese members, the “first boys,” are unnamed. Most likely the Chinese cooks are not even shown. Sai Wo Studio. Hong Kong. 1935. “Catering Department R.M.S. Empress of Japan.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00329. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0216646.

The Grip of Exclusion Tightens

While history around Chinese Exclusion has focused mostly on its impact on migrants who intended to stay in Canada for longer terms, these laws also often explicitly target the freedom of movement of Chinese sailors. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, immigration policies in Canada and the United States increasingly show a deep discomfort of the role of Chinese seamen in foreign trade.[11] After 1900, laws tightened further. The 1906 British Merchant Shipping Act, introduced language requirements that sought to exclude South Asian and Chinese mariners, the so-called “coolie and lascar” sailors.[12] Later, U.S. legislation, such as the 1917 Asiatic Barred Zone Act and the 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act, imposed steep head taxes, mandatory photo IDs, confinement aboard boats at anchor, or even bond requirements on Asian seamen.[13]

Chinese Sailors at a hostel in Liverpool. Men lived in crowded, dirty conditions in unmaintained buildings in ports around the world, often close to the urban core or red light district. This transient, male-only environment is one that echoes with that of Chinese men in labour camps and SRO hotels, the so-called “bachelor society.” Bert Hardy. May 1942. “Interior Chinese Hostel, Liverpool.” Picture Post. 1136. Getty Images via The Guardian. Accessed Jan 16 2025.

By 1925, the British Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order compounded these restrictions by requiring non-white sailors to register and carry identity documents, with the goal to drive away as many Chinese, South Asian, and Black sailors from their international fleet. This was important in a Canadian context, as all the Canadian Pacific’s Empress liners were British-owned and registered. The Chinese Nationalist government also introduced measures in the 1930s and 40s mandating overseas Chinese to register if they wished to remit earnings home or re-enter China. These overlapping policies subjected Chinese sailors around the world to constant surveillance and financial strain.

Navigating Vancouver’s Waters

By this time, Vancouver’s port had been a crucial transit point for Chinese sailors navigating trans-Pacific routes since becoming the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1887. The city’s Chinatown became a sanctuary for mariners who jumped ship, using shared clan and hometown connections to integrate into Chinese communities across the province.[14] From the 1870s to the 1970s, thousands of sailors disembarked illegally this way in North American ports like Vancouver, Halifax, and New York, often evading strict immigration policies.[15]

This very rare CI 46 Certificate was carried by Luke Ko, born to the prominent Ko Bong family of Victoria, in the 1930s. His photo was on the other side. It forms part of The Paper Trail Collection at UBC RBSC, where you can learn more about his life. Dominion of Canada. Department of Immigration and Colonization. Chinese Immigration Service. Victoria, BC. 18 Jan 1932. “C.I.46 Certificate of Luke Ko Bong.” UBC RBSC Paper Trail Collection. RBSC-ARC-1838-DO-0459r. Courtesy of the Ko Bong Family.

The Canadian Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 added layers of bureaucracy for Chinese mariners.[16] Shipping companies were required to list all Chinese crew members on special ledgers, with heavy fines imposed on the company for any absentees. Despite this, sailors found ways to subvert these measures, purchasing fraudulent identity documents to remain in Canada or assuming the identities of Chinese Canadians who had paid the head tax or were locally born. The stories of these “paper sons” exemplify the resourcefulness of Chinese mariners in circumventing exclusionary laws.

During World War I, Chinese mariners began to appear in more visible roles, above deck on Canadian Pacific’s Empress ships. Some became closer friends and coworkers to senior officers, like the Chief Stewards, Ships’ Surgeons, and Head Purser (Paymaster.)[17] These closer connections and better jobs sparked a backlash from white sailors’ unions and exclusionists, especially in British Columbia.[18] Debates in Canada’s House of Commons during the 1930s centered on whether the company should be penalized for hiring Chinese sailors over white Canadians while they received a large government subsidy.[19] While a 1937 recommendation to cut federal aid for Canadian Pacific failed, it highlighted the entrenched racism these workers faced.[20]

Acts of Resistance

Despite these challenges, Chinese sailors fought back. Beyond the 1922 Hong Kong Seamen’s Strike, there are many smaller examples of collective action. Sailors staged walk-offs, work slowdowns, or shared political and immigration information with Chinese migrants en-route to their new lives. The Lianyi Society (Chinese Sailors Society), working with popular Cantonese opera troupes, smuggled letters from revolutionaries and literature to communities around the world.[21]

Later, during World War II, 83 Chinese seamen in Halifax were detained for seven months after demanding hazard pay for navigating the treacherous North Atlantic warzone.[22] In February of 1942, 14 more Chinese seamen from Hong Kong escaped the Nova Scotian port after being rescued from a torpedoed ship and brought to the immigration station ashore, costing their employer 21,000 CAD in forfeited bonds under the Exclusion Act provisions.[23] That same year, two dozen Chinese crewmen in Vancouver sued their employer for false imprisonment when they were handed over for immigration detention after walking off the boat for higher wages.[24] Although these efforts often ended in deportation or legal defeat, persistent acts of resistance underscore Chinese sailors’ determination to assert their rights.

Lee Ah Ding (left) and Yee Chee Ching, Chinese seamen from a British freighter, try typical American food for the first time. Chinese sailors were denied shore leave in the USA even during wartime, until diplomatic negotiations loosened restrictions slightly. It is unclear if Canada also relaxed its harsh laws. United States Office Of War Information, Gruber, Edward, photographer. First Chinese seamen granted shore leave in wartime America. New York, USA. Sept 1942. Photograph. US Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017693642/.

Sustaining Community and Culture

The contributions of Chinese sailors extended far beyond their roles aboard ocean liners, the merchant marine, or international trade. Traveling through global waters, they brought news and goods to isolated Chinese workers in canneries, sawmills, and mining communities along British Columbia’s northern and central coast.[25] Cooks on coastal ferries, steamers, and mail ships, like famous author Wayson Choy’s father, endured long hours away from family with the hope of saving.[26] Often they worked alongside their “cousins and uncles” from the same village clan, and when one retired, either to the village in China or to a Canadian Chinatown, they sought to replace them with another relative in need of work.

Two Chinese cooks and crew with three white children from Rivers Islet, BC on steamer to Metlakatla BC (a Tsimshian village). Chinese coastal ferry workers were a critical part of maritime connections between isolated settlements along the vast Pacific coast. Unknown Photographer. ca 1908. “Fred Grant and family on the S.S. Coquitlam” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC-PH-11350.

Post-War Transitions and Decline

After World War II, changes in the maritime industry and immigration policies transformed the lives of Chinese sailors. The American Chinese Exclusion Act ended in 1943, with the Canadian Chinese Exclusion Act following in 1947, though strict quotas and restrictions remained in both countries. Many young men fleeing the Chinese Civil War joined ships to escape turmoil, hoping to find new opportunities abroad. Despite their willingness, these working-class men were often passed over as precious quota spots were filled by wealthy and educated elites, unless they had a family member in Canada who could try to help them come.

In the 1950s and 1960s, shipping companies like the President Lines depicted here tried to update their fleets to reflect the sleek modernist tastes of the time. This American company had strong traffic from Chinese Canadians post-Exclusion as an affordable way for elderly bachelors to retire in China, or for families to come to North America for reunification. Eventually, passenger service on these boats was supplanted by air travel and the company pivoted to shipping. Palmer Picture. ca 1950. “Chefs and Servers in a Dining Area.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC-PH-11365.

The decline of trans-oceanic steamship routes further reduced opportunities for Chinese mariners. With travelers increasingly turning to air travel, shipping moved away from passenger traffic and towards shipping containers, reducing the need for cooks on vessels. Travel to China also steeply declined following the Korean War embargoes, although ties to Hong Kong remained strong. By the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese sailors in Canada were primarily employed as cooks and stewards on BC Coastal Ferries. Relatives, former classmates, and friends would vouch for new arrivals; this ability to support one another is a contributing factor to why Chinese cooks had a virtual monopoly over coastal vessels until the 1970s. For some, this was their first job in Canada, and a way to learn English and culinary skills that would allow them to open their own businesses; a path to the middle class. Programs like the 1960 Chinese Adjustment Statement provided amnesty for those who had entered Canada illegally, many of whom were former sailors.

Conclusion: Contemporary Parallels

Today, Canada’s ports continue to host crews from around the world, many of whom endure exploitative working conditions reminiscent of earlier eras. Most ships visiting Vancouver operate under “flags of convenience”—registered in countries with lax labor and safety standards—leaving their multinational crews vulnerable. Most modern sailors come from countries previously colonized by European powers. Advocacy groups continue to work to improve conditions for these modern mariners, offering legal aid, welfare visits, and essential supplies.

The history of Chinese sailors in Canada’s maritime industry reveals a story of perseverance and adaptability amid systemic racism and exploitation. Their labor was instrumental in connecting Canada to the global economy, yet their contributions remain underrecognized. By examining their struggles and achievements, we not only honor their legacy but also shed light on the ongoing challenges faced by seafarers worldwide.

If inspired to assist, consider supporting organizations dedicated to improving the welfare of sailors visiting Canadian ports, ensuring their dignity and rights are upheld in the modern era.

Footnotes

[1] You can learn about this history at the Chung Lind Gallery

[2] For example, this story about the Batavia in The Vancouver Daily News Advertiser

Thu, Aug 09, 1888 ·Page 3

[3] The Chung Collection holds many versions of blueprints of the Empress of Asia. Some show annotations which indicate the quarters of Chinese workers and passengers, located in segregate settings near the stern.

Canadian Pacific Railway Co. 1945 “Empress of Russia and Empress of Asia general arrangement plans” RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-OS-00119

[4] Records related to Blue Funnel line can be found at UBC RBSC and City of Vancouver archives. Their ship names are commonly seen on the General Register of Chinese Immigration and head tax certificates. The Liverpool Maritime Museum holds some of the company records in their archives.

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/records-of-blue-funnel-line-ocean-steam-ship-company

[5] https://dragonsandlions.co.uk/

[6] Kwok-Fai Law, Peter. “The Political Pragmatism of Steamship “Teaboys”: Reassessing the Chinese Labor Movement, 1927–1934.” Twentieth-Century China 46, no. 3 (2021): 287-308. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/tcc.2021.0025.

[7] Headlines about drug smuggling from sailors are common in BC and other North American ports through the 1970s. It is also a trope in some Hong Kong cinema films.

[8] Glick, Gary W. 1969. “The Chinese Seamen’s Union and the Hong Kong Seamen’s Strike of 1922.” Masters Thesis. History Columbia University. New York City, USA.

[9] In 1910 Lianyi was founded in San Francisco. Soon after a hub in Yokohama in a tailor shop. By 1915 central offices were in Shanghai, then Hong Kong, then Guangzhou. Operations ceased in 1927. The union used fake corporations to obscure their operations. (Huang Langzheng 黃郎正, “Brief Account of the Chinese Ocean Seamen Union 聯義社之概述” Kwangtung Culture Quarterly 廣東文獻季刊. Iss. No. 2. June 1, 1973

[10] For example: The Vancouver Sun Tue, Feb 28, 1922 ·Page 11; The Vancouver Sun

Sun, Jul 23, 1922 ·Page 12

[11] Canadian Head Tax in 1885 had no provision for Chinese Sailors, so their status was a gray area. In 1902 there was an attempt to land a Chinese crew of 30 in Victoria to staff a Seattle Ship on way to Russian Far East, which the government blocked through an administrative order (The Vancouver Semi-Weekly World, Dec 26 1902 Pg.5.) From 1882-1902, it was also a gray area for Chinese sailors in USA Exclusion laws. From 1903-1917 shipping lines to USA had to post 500 dollar bond forfeited if Chinese sailors hopped ship.

[12] Urban, Andrew. 29 Oct 2018. “Restricted Cargo: Chinese Sailors, Shore Leave, and the Evolution of U.S. Immigration Policies, 1882-1942.” Online Article. Rutgers University. New Jersey, USA. Accessed Jan 17 2025. https://t2m.org/restricted-cargo-chinese-sailors-shore-leave-and-the-evolution-of-u-s-immigration-policies-1882-1942/

[13] Urban, Restricted Cargo. 2018

[14] The Montreal Star Mon, Jul 11, 1910 ·Pg. 4

[15] Pegler-Gordon, Anna. 2021. Closing the Golden Door: Asian Migration and the Hidden History of Exclusion at Ellis Island. 1st ed. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/9781469665740_pegler-gordon.

[16] Library and Archives Canada. Statutes of Canada. “An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration, 1923.” Ottawa: SC 13-14 George V, Chapter 38. Sec. 25

The text of the Act allowed for Chinese sailors to land and then ”re-ship” with other outbound employment, but days after it was enacted this freedom was repealed by Order in Council (E.C.1275) and cash bond instated.

[17] Some would pool together money for an engraved plaque when these men moved to other boats or retired after long service. (Victoria Daily Times Jan 3 1933 Pg.8)

[18] Survey of Race Relations. 1924-1927 “Testimonial meeting on the Oriental, I.W.W. Hall, Cordova Street” Stanford University. Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. Box: 24, Folder: 16. Accessed Jan 17 2025. https://purl.stanford.edu/bd797xr7521

[19] Letter to Editor supporting Chinese sailors (Vancouver Sun Feb 10 1937 Pg 4)

Criticism of letter above: (Vancouver Sun Feb 13 Pg 4)

[20] House of Commons Journals, 18th Parliament, 2nd Session : Vol. 75 Pg.81-82

[21] A comprehensive history of Lianyi Society was published by Huang Langzheng in Hong Kong in 1971 titled 聯義社社史. The Lianyi Society overlapped with Hong Kong’s 八和會館opera union. There is an interesting connection through Red Boat travelling operas 紅船 , which link sailors, opera, kung fu, and secret societies.

[22] Meredith Oyen, “Fighting for Equality: Chinese Seamen in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1939–1945” Diplomatic History, Volume 38, Issue 3, June 2014, Pages 526–548, https://doi.org/10.1093/dh/dht106

Mention also of this incident in William Lyon Mackenzie King’s journals.

[23] Regina Leader-Post, Feb 21, 1942 ·Page 19

[24] The Vancouver Province Oct 21, 1942 ·Page 8

[25] Christenson, Neil H. “All the Princesses’ Men: Working for the British Columbia Coast Steamship Service 1901-1928” Masters Thesis. Eastern Washington University. Spring 2022. EWU Digital Commons. Accessed Jan 17 2025.

[26] Choy, Wayson. “Paper Shadows: A Chinatown Childhood.” Toronto: Penguin Books, 2000.

This path was also true for writer Fae Myenne Ng, as recounted in Ng, Fae Myenne. “Orphan Bachelors: A Memoir : On being a Confession Baby, Chinatown Daughter, Baa-Bai Sister, Caretaker of Exotics, Literary Balloon Peddler, and Grand Historian of a Doomed American Family.” New York: Grove Press, 2024.

No CommentsPosted in Chung, Chung | Lind Gallery, Collections, CPR, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Highlights, Immigration and Settlement, Research and learning | Tagged with British Chinese History, Canadian Pacific Railway, Chinese American History, Chinese Canadian History, Labour History, Maritime History, Sailors, Seamen, Trans-Pacific

New Years 1932 Menu, the Empress of Britain World Cruise

Posted on January 3, 2025 @11:15 am by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is special edition of RBSC’s new series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

Happy New Year from the Chung Lind Gallery and the whole UBC Rare Books and Special Collections team!

Canadian Pacific Railway Company, and Lawrence Crawford. 1932. “Empress of Britain World Cruise New Year Dinner 1932.” M. Chung Textual Materials. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0373316.

As we glide into 2025, may we all have a chance to experience some of the finer things in life, as these passengers aboard the 1932 Empress of Britain world cruise certainly did for this New Year’s Day feast. With a ten-course meal plus dessert, there was ample opportunity to ring in the New Year with a cornucopia of plentiful food.

The cover of this advertising pamphlet for the 1931-1932 World Cruise features an Indonesia Shadow Puppet.

Canadian Pacific Steamships. 1931. “Empress of Britain World Cruise 9th Annual.” Advertisements. Chung Textual Materials. USA : Unz & Co. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0362227.

Pg.1

The Empress of Britain was the largest ship in the Canadian Pacific Steamship Co and considered the most luxurious. On Dec the 3rd 1931, she departed New York to begin her 128-day world cruise. During the Depression, this was a luxurious journey only very few could afford, with tickets starting at around $2000 USD per person at the lowest fare ($66,700 CAD in Jan 2025.) Posters and pamphlets advertised the “exotic locales” and opulent Jazz-Age interiors of the vessel, hoping to nab elite leisure visitors from the Anglo-American upper-crust. Servants like valets and maids could travel for lower rates, in cabins deeper in the ship. There were many shore excursions if you chose to leave “the floating palace.” On this voyage, the passengers spent ate their New Years dinner ashore on the banks of the Nile River near Cairo and the Pyramids, having spent Christmas in Mandatory Palestine.

Canadian Pacific Steamships. 1931. “Empress of Britain World Cruise 9th Annual.” Advertisements. Chung Textual Materials. USA : Unz & Co. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0362227.

Pg. 4

The menus of CP Empresses leaned strongly towards continental cuisine, especially French, with an emphasis on meat, seafood, and rich sauces. Between you and me, for this meal I’d skip the chicken in braised celery and clear sauce and go for the Tournedos Rossini (filet mignon pan fried in butter with a topping of pate, black truffle, and Madeira wine sauce.) On Pacific voyages, the Chinese chefs would prepare Chinese cuisine for the majority-Asian steerage passengers.

Canadian Pacific Steamships. 1931. “Empress of Britain World Cruise Fares.” Advertisements. Chung Textual Materials. United States : Canadian Pacific Railway Company. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0372252.

Pg.3

Keep an eye out for new stories from the Chung and Lind Collections throughout 2025, and for new programming to come!

Let us know if you would like more blogs about food and the Chung collection!

Further Reading

Turner, Gordon. (1992). Empress of Britain

No CommentsPosted in Chung, Chung | Lind Gallery, Collections, CPR, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Highlights | Tagged with 1932, Canadian Pacific Railway, Empress of Britain, Food, Menus, New Years, Pamphlets, Posters, World Tour

Season’s greetings from RBSC!

Posted on December 23, 2024 @9:37 am by Chelsea Shriver

Winter Scene, Grouse Mountain Chalet. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_01_0110

Just a reminder that the Rare Books and Special Collections satellite reading room will be closed from Wednesday, December 25, through Wednesday, January 1, inclusive. Additionally, the RBSC offices will be closed on the following stat holidays: Wednesday, December 25; Thursday, December 26; and Wednesday, January 1.

RBSC’s offices and our satellite reading room will reopen on Thursday, January 2.

We look forward to seeing you in the New Year!

No CommentsPosted in Announcements, News, Services | Tagged with

The S.S. Tartar and the Tale of “Soapy” Smith

Posted on December 21, 2024 @9:57 am by Emily Witherow

This blog post is part of RBSC’s new series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

CC-PH-02827 – Starboard view of the CPR SS. Tartar at wharf in Vancouver, BC, 1897.

The SS Tartar, pictured above at a wharf in Vancouver, BC, was one of two steamships that the Canadian Pacific Railway purchased in 1897. They did so with the intention of capturing a portion of the Klondike Gold Rush traffic, as stampeders traveled northward from San Francisco, Seattle, Victoria, and Vancouver to Alaskan ports in Skagway, Juneau, and Dyea. Although the Tartar and its companion, the SS Athenia, completed their weekly route from Vancouver to Skagway only six times before they were withdrawn from service in July 1898, the steamship became an unlikely figure in the saga of the American con man Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith. On July 12, 1898, the Tartar arrived in Skagway just in time to carry ten of Smith’s accomplices to Seattle, who were “hunted like wild beasts” and exiled by local citizens following Smith’s death a few days earlier.[i]

RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-0990 – “Soapy Smith’s Saloon” in Skagway, Alaska, complete with a Soapy Smith dummy that, when you enter the front door, raises his glass to you and his eyes light up when you go through a far door. Taken ca. 1930.

re based on swindling travelers in Skagway, such as his famous “prize soap racket” where he would sell bars of soap which had the chance of containing money bills; of course, none did. As Smith’s cons redirected mining traffic away from Skagway, which became known for its crime and crooks, the local townspeople were outraged and formed a vigilante committee to restore law and order. On July 8, 1898, Smith exchanged shots with a member of the committee, City Engineer Frank Reid, with both men dying from their wounds. Reid’s funeral was the largest in Skagway history, with his gravestone inscribed with the words: “He gave his life for the honor of Skagway.”

More than a century later, Jefferson “Soapy” Smith lives on in through a myriad of biographies, a dedicated museum in Skagway, and an annual Soapy Smith Wake on July 8, though the SS Tartar has been relegated to the back pages of those stories. After 1898, CPR re-directed the ship to supplement the Empresses on the Pacific trade route.

Both the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, and the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, have materials touching on this episode of history. For more images, documents, and information about “Soapy” Smith and the CPR’s coastal steamships, plan your visit to the Chung Lind Gallery here!

[i] “Skaguay’s First Shipment of the Unwelcome,” The Daily Alaskan, July 12, 1898, p.4, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2017218619/1898-07-12/ed-1/seq-4/; “Arch Desperado Dead,” The Daily Alaskan, July 11, 1898, p. 3. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2017218619/1898-07-11/ed-1/seq-3/

No Comments

Posted in Chung, Chung | Lind Gallery, Collections, CPR, EarlyBC, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Immigration and Settlement, Lind, Research and learning | Tagged with Canadian Pacific Railway, Chung Collection, Chung Lind Gallery, Klondike Gold Rush, Lind Collection

Within the Gaps Exhibition

Posted on December 17, 2024 @9:24 am by Claire Malek

Within the Gaps: Intracommunity Voices in Chinese Canadian and Korean Canadian Records

December 10, 2024 to February 9, 2025

Asian Library, Asian Centre

1871 West Mall, UBC Vancouver

Re-posted from UBC Asian Library Blog

The UBC Asian Library and UBC Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC) are excited to present “Within the Gaps: Intracommunity Voices in Chinese Canadian and Korean Canadian Records.” This exhibition, which is located at Asian Library, Asian Centre, has been made possible through the Asian Canadian Research and Engagement (ACRE) Faculty Initiatives Grant. The project explores how communities are filled with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and voices. The exhibition brings forward voices from Chinese Canadian and Korean Canadian records that touches on the polyvocality of these communities in British Columbia.

The Chinese Canadian section of the exhibit considers the Janet Smith murder: a famous cold case from the 1920s in which Wong Foon Sing (黃煥勝), a Chinese houseboy, was charged with the murder of housemaid Janet Smith. While most narratives focus on uncovering the real murderer, this exhibit re-shifts the focus to Wong Foon Sing. Charged for a murder in which he was never a serious suspect, Wong’s silencing and abuse by civil authorities reflect the turbulent environment surrounding race, class, and systemic corruption in 1920s Vancouver. RBSC houses the records of three individuals related to the case, but this exhibit provides a unique opportunity to view the material on display. By showing the records of these three figures—who all occupy positions of power—the exhibit encourages viewers to reflect on the voices not represented in these records, as well as the complexities within a given community that cannot be wholly represented by a single spokesperson from that community. This exhibit also features replicated pages from scrapbooks belonging to the Wongs’ Benevolent Association in hopes of foregrounding voices that have been undermined in dominant narratives of the Janet Smith case.

The Korean Canadian section of the exhibit explores the disparate accounts of Korean Canadians in British Columbia. This history is constructed through a reflection on how gaps are perceived in the sources available on Korean Canadian history. On display are records of early academics at the University of British Columbia in the 1950s and 1960s, records of Korean church members, and accounts of the Korean Canadian community from individuals themselves. This display asks viewers to see several Korean Canadian experiences by viewing different feelings, thoughts, and descriptions from within and without the community. This exhibit features reproductions from the Pacific Mountain Regional Council Archives of the United Church of Canada to highlight community voices and link back to stories found in the University of British Columbia Archives and RBSC (specifically, the Korean Canadian Heritage Archive and Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection).

Overall, this exhibition hopes to dispel the notion of communities as simple monoliths and instead, highlight the complex range of voices within a given community. How do we understand the categories “Asian Canadian,” “Chinese Canadian,” and “Korean Canadian”? Where do gaps exist in the voices of those communities? When do those voices become valuable, and who determines the value? Who is listening?

Additional resources:

- [Report on funds raised and expenses for the defense of Wong Foon Sing]. CC_TX_279_020. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0354895

- [Scrapbooks] from Foon Sien Wong fonds. RBSC-ARC-1628-01-01. https://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/scrapbooks-1970

- Korean Canadians. CC-TX-300-54-p.25. From https://rbscarchives-tst.library.ubc.ca/at-first-a-dream-one-hundred-years-of-race-relations-in-vancouver

Posted in Chung, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Immigration and Settlement, Research and learning | Tagged with

Part 2: A Tale of Seattle’s Chinatown

Posted on December 7, 2024 @12:00 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog is a continuation of a series exploring a letter in the Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. You can find part one HERE.

Thanks to Jeffrey Wong for assistance on translation, and to the staff at the National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle branch.

THE MAN, THE LETTER

The story of the Shaunavon Crystal Bakery, introduced to me by a single letter found in the Chung Collection, offered an intimate lens into the lives of every-day Chinese Canadians: their resilience, and the vibrant networks of family and business they built across the Prairies and beyond. As we shift our focus from Saskatchewan to Seattle, we’ll explore how these transnational connections informed another story, beginning with Harry K. Mar Dong, the letter’s recipient.

First off, what does the letter itself say?

“To Younger Brother Gim Dong,

Last time I received a letter from you about these matters, but I haven’t heard back from you about things and miss folks dearly. I am now writing to you to inquire if all was done properly regarding Oct 30th money transfer to Hong Kong so that [Mah] See Gey can pass over the $300 cash to [Mah] Gay Yun. I have yet to hear from See Gey that he has received this money and the last money I sent previously, so now I’m asking you now if you can inquire on both the money transfers to ensure they have received.

From Gim Sing.”

This letter is a somewhat everyday business affair that reflects some of the dynamic networks that connected the Chinese Canadian and American communities, namely those for sending money back to family in China. From our small town of Shaunavon, Saskatchewan, this author is writing to a broker, someone who is a trusted and maybe powerful member of the Mah clan who is facilitating the transfer of these hard earnings. That person is Harry K Mar Dong.

Citizen’s Travel Card used by Harry K Mar Dong to cross into Canada, NARA Seattle, Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files series, Mar Dong, Box 566, Case File 7030/4626

According to historical records, Mar Dong was born in 1881 above a shop in San Francisco Chinatown, to a shopkeeper and his wife. When interviewed by US Immigration in 1923, he had sworn witnesses to attest to this fact, and even his mother’s death certificate, to establish he was a native-born US citizen. This all, however, was false. Mar Dong was a “paper son.” [1]

The term “paper sons” refers to Chinese immigrants who entered the United States and Canada by falsely claiming citizen status, domicile, merchant status, or descent from citizens using real or fake government documents. This practice grew widespread after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which destroyed city records, allowing many Chinese individuals, including Mar Dong, to claim U.S. citizenship. These claims often involved elaborate stories and forged documents, helping immigrants bypass restrictive laws like the US Chinese Exclusion Act and build new lives in America.

Detail from a depiction of the 1886 Anti-Chinese Riot at Seattle, “The anti-Chinese riot at Seattle, Washington territory / illustrated by W. P. Snyder,” Harper’s Weekly Magazine, 6 Mar 1886. Chung Collection, RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-TX-288-94

According to Mar Dong’s son Al Mar, the real story is that his father arrived in the United States in the late 1800s with a brother, working in Montana, and then Seattle, where he witnessed the violent 1885-86 anti-Chinese riots.[2] By the 1920s, Mar became a powerful labor contractor managing mostly Chinese and some Filipino cannery crews. When US canneries moved towards employing more of the latter, his business declined. He did not lose his status though, for he soon became a transportation agent for the many transportation companies that Chinese immigrants relied on to travel in a world of Exclusion barriers.[3] Maybe these is the reason he bought papers to establish his US citizen status, which would improve his business and personal legal protections.

You can learn more about the Chinese Diaspora’s role in the Pacific Northwest cannery industry and the importance of Chinese ticket agents at the Chung Lind Gallery.

By 1924, Mar Dong was the official Chinese agent for the Admiral Oriental Line, a steamship line with offices across the globe, and was meeting their regular ship arrivals in Canada every month by taking coastal ferries like the CPR Princesses to Victoria and Vancouver. This required the swift navigation of both the US and Canada’s labyrinthine Exclusion regulations. However, with powerful friends in the shipping industry, this was possible. In fact, Mar Dong was issued a special permit and ID card to cross with their assistance. Emboldened, he even tried to get permission to cross on CPR ships without being manifested, a bold tactic that most of the poor, single Chinese workers could never dare to try, fearful of being deported or turned away on arrival.[4]

Mar Dong in the 1930s, “Form 430-Application of Alleged American Citizen of the Chinese Race for Preinvestigation of Status, Seattle.” NARA Seattle, Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files series, Mar Dong, Box 566, Case File 7030/4626

In 1926, Mar was implicated in an affair where a detained potential immigrant, Wong Yick, sought entrance to the US. Ticket agents were powerful brokers, often using bribes, false papers, and political influence to shape Chinese movement across borders, but also could exploit these migrants for profit. According to Al Mar, his father was deeply enmeshed in this trade of paper lives.[5] The incident above may or may not have involved shady dealing, but it definitely involved the strategic deployment of a box of feces.[6]

The Hotel Mar

In 1927, one of Mar Dong’s most lasting legacies was completed: The Mar Hotel building, still standing at 507–511 Maynard Ave. S. in Seattle. It was at this address that our humble letter arrived in 1944. This building became the hub of Mar’s offices, his ticketing and money transfer business, as well as a bustling residential hotel. The Mar Café, yet another business of his, opened on November 10, 1927, with a public announcement in the Seattle Star proclaiming that it was not only “offering under Oriental atmosphere-the best food, best service-Chinese and American food, dancing and music” but that it was “The only original Chinese Cafe in America.”[7]

Big banquets of both the White and Chinese community were held there in the following years, with one notable occasion featuring the full live orchestra from the SS President Pierce.[8] It’s no coincidence that this steamship was part of the Dollar Steamship Co. and American Mail Lines fleet that Harry K. Mar Dong was now the Chinese agent for. Harry Mar Dong was also a founding executive of the Seattle branch of the powerful Hoy Sun Ning Yung Benevolent Association when it was formally incorporated in 1928.[9] The celebratory banquet, with delegates from across the North American Toisanese diaspora, was held at the Cafe Mar in the Mar Hotel.[10]

Inside cover of a pocketbook with details on Mar Hotel and Company, note the exterior image. “Note book of a Mar clan member” 1933, Chung Collection, RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-TX-102-18-1

The Mar Hotel was often called the “Hong Kong Building” after the Mar Café transitioned into the popular Hong Kong Restaurant.[11] In the 1930s, the Mar Hotel hosted an infamous nightclub and dance hall called the Hong Kong Chinese Society Club, nicknamed the “Bucket of Blood.”[12] During the latter years of Prohibition, the club was raided, catching some of Seattle’s blue-blues red-handed at the craps table, sipping on bootleg whiskey (potentially smuggled from Canada) and in-house moonshine.[13] The blaring headlines did not stop the community of mostly Chinese men living in the tiny single rooms of the Mar Hotel, or even some famous Chinese visitors, from making use of this so-called “sordid structure” as a place to lay their head at night.[14] The Mar family continued to run the Hotel until 1941, when Al Mar sold it. Interviewed by the Seattle Times about his father in 1993, Al remembered his father as ““jolly; he was one of Chinatown’s most prominent members, but he wasn’t that Chinafied; a lot of his association was with the lo fan [white folks, lit. barbarians 佬番].”

: Letterhead from Hotel Mar, “Pad of writing paper from the Hotel Mar (馬登旅館) in Seattle, Washington” Unknown, Chung Collection, RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-TX-102-8-1

In the early 1950s, the Sakamoto family, survivors of internment at Minidoka and Tule Lake Camps, purchased the Mar Hotel. Daughter Janet Sakamoto provides the following description of residential hotel life:

“Our family had the entire second floor of rooms where we lived right next to the lobby. We children didn’t go upstairs to the floors where the guests were staying. At the top of the stairs from the first to the second floor was the lobby with a check-in desk, mailboxes, and a switchboard system connected to the rooms. There was also a huge kitchen and a ballroom floor that was once part of a restaurant. It wasn’t used when we bought the hotel and hadn’t been for years. We rode our bicycles on the marble dance floor. Most of our residents were either white or African Americans who worked in the neighboring train stations or jazz clubs. Sarah Vaughn and Count Basie stayed at our hotel along with other Black entertainers who weren’t allowed to stay in the other downtown Seattle hotels.”[15]

Living legacies of objects, place and space.

The lives of those who inhabited hotels like the Hotel Mar often represent a historic cross section those most marginalized by urban society: poor Chinese bachelors, single working-class women, sex workers, transient LGBTQ+ folks, performers, homeless, addicted, widowed seniors on fixed pensions, and more. By 1971, the Mar Hotel closed, but the building continued to live on the street level. Seattle icon Ron Chew shares a memory from his time as a busboy with his head waiter father at the Hong Kong Restaurant downstairs:

“The Chinese men had very Spartan lives… A lot of the kitchen help lived in the Mar Hotel upstairs or other hotels in the district. You learned things from paying attention to the men you worked with…you’d just know some things without their saying a word. Picture yourself…12 hours, non-stop with a few breaks for food…standing and running back and forth with trays that weighed 50 pounds. You could do it in your twenties and thirties, but forties, fifties, sixties, seventies…it wasn’t a way to live your life. Some of the waiters faded away because they couldn’t continue to handle the ten to fourteen hour days on their feet. Both waiters and busboys would be so tired at the end of the day…you’d open up the door and smell the air outside of the kitchen along with your own clothes that smelled of grease and subgum.”[16]

One of the main reasons inspiring me to write this series was to highlight how our encounters with daily objects, or even the spaces we inhabit and move through each day, can connect us back to a deeper history if we seek it. Behind each archival object is a real memory, a person with a family and story. In the case of the Chinese diaspora community, these are stories that have been too often ignored, erased, appropriated, or papered over. Working class stories are minimized or forgotten. Real work remains to reclaim the archive as a place of reconciliation and community story sharing.

The same holds true for physical spaces, especially Chinatowns, which currently face displacement across North America. Returning to our narrative, the Hong Kong Restaurant in the Mar Hotel closed in mid to late 1980s, a period corresponding with many beginning to move away from Chinatowns to suburbs. Entrepreneur James Koh purchased the historic Mar, Milwaukee, and Alps residential Hotels in Chinatown in 2003. By 2008 the Mar reopened with offices for rent.[17]

I hope you have enjoyed this two-part series, please keep an eye out for continued blogs about the Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collections, as well as the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection on this webpage or HERE.

The Hotel Mar or “Hong Kong” Building, 507 S. Maynard Ave., Seattle, Washington, U.S.,1975. Item 195772, Historic Building Survey Photograph Collection (Record Series 1629-01), Seattle Municipal Archives.

Further Reading

Groth, Paul. Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999

Wong, Marie Rose. Building Tradition: Pan-Asian Seattle and Life in the Residential Hotels. First ed. Seattle, WA: Chin Music Press, 2018.

Endnotes

[1] NARA Seattle, Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files series, Mar Dong, Box 566, Case File 7030/4626

[2] Links To History — Passengers And `Paper Sons’ In Chinatown, The Seattle Times, Sep 5 1993, Online Edition, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/19930905/1719427/links-to-history—-passengers-and-paper-sons-in-chinatown

[3] McKeown, Adam. Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders. 1st ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

[4] There are extensive correspondences on these dynamics or border crossing in Mar Dong’s Seattle Chinese Exclusion Act case file. Reference above.

[5] Links to History, Seattle Times, 1993

[6] Mar had to provide some excuses for this incident to immigration authorities and was banned from the building for a time. NARA Seattle, Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files Series, Mar Dong.

[7] Seattle Star Nov 10 1927 Pg.3

[8] Seattle Union Record Jan 11 1928 Pg.3

[9] 台山寧陽會館 the Native-place association for those from Taishan/Toisan county. Notably, both Mar Dong and our Mah men of Crystal Bakery in Shaunavon are Toisan men. Perhaps they came from the same village area?

[10] Seattle Star, Dec 8 1928 Pg.2

[11] Historic South Downtown Oral Histories: Marie Wong Discusses Her Research on Seattle’s SRO Hotels and the Men and Women Who Lived in Them, historylink.org. Essay 11135. Nov 2 2015. https://www.historylink.org/File/11135

[12] Wong, Marie Rose. Building Tradition: Pan-Asian Seattle and Life in the Residential Hotels. First ed. Seattle, WA: Chin Music Press, 2018. Pg.248

[13] Seattle Star, Feb 12 1931 Pg.1

[14] Famous General Fang Zhenwu 方振武 (Fang Chen/Cheng-Wu) stayed at the Mar Hotel while on his North America leg of a two year anti-Japanese imperialism tour in 1936 (Seattle Star, May 27 1936 Pg.2) . He later stopped in Victoria and Vancouver (see RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-TX-301-23). General Fang was assassinated by the KMT in 1941.

[15] Pg. 236, Building Tradition, Wong

[16] Pg.298, Building Tradition, Wong

[17] Pg.332, Building Tradition, Wong

No Comments

Posted in Chung, Chung | Lind Gallery, Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Highlights, Immigration and Settlement, Research and learning, Uncategorized | Tagged with BC Coast Steamships, Chinatowns, Chinese American History, Chinese Canadian History, Chung Lind Gallery, Correspondence, Guangdong, History, Hotels, Immigration, letters, Mar Dong, photos, Restaurants, Saskatchewan, Seattle, Vancouver, Victoria