What’s That Number?

Posted on May 14, 2024 @4:57 pm by Claire Malek

Many thanks to guest blogger Lily Liu for contributing the below post! Lily is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and recently completed a Professional Experience with Rare Books and Special Collections Library.

What’s That Number? A Thirty-Minute Dive into Deciphering a Traditional Chinese Numeral System

During my time working with the Lock Tin Lee fonds at the RBSC, I came upon a certificate that used a number I had never seen.

Image 1: close-up of a number I did not recognize

From my RBSC peers, I learned that this number belonged to a system called Suzhou numerals (苏州码子; 蘇州碼子). As per their namesake, these numerals originated from the Suzhou region in China and were a traditional numeral system used by the Chinese before the introduction of Indo-Arabic numerals. Due to its ease of use, the Suzhou numeral system was popular amongst merchants, bookkeepers, and other calculation-centric occupations. It is the only surviving variant of the rod numeral system still in use today and can be found in the markets, old-style tea restaurants, and traditional Chinese medicine shops in Hong Kong and Macau.*

But what was the number on the certificate specifically? It did not correspond immediately to any numbers on the comparison chart for Suzhou numerals.

Image 2: comparison chart for Suzhou numerals

Deciphering the number became a collaborative effort between my curious roommate, myself, and the comparison chart. Our thought process proceeded as follows:

Option 1: 42?

〤 and 〢 are accounted for, but there are two additional horizontal strokes to the right that do not correspond to any number immediately on the chart, and the strokes look too intentional to be a mistake.

Option 2: 417?

Perhaps the writer just really elongated the short vertical stroke on top of the Suzhou numeral “7” (〧), and just really missed the stroke’s centre positioning and shifted it to the left? Yes…we were pushing it.

Image 3: a visual explanation supplied by my roommate

Option 3: 422!

My roommate spotted the smaller text that noted exceptions to the standard comparison chart.

Image 4: Wikipedia excerpt explaining exceptions to the numbers’ forms

Essentially, because numbers 1, 2, and 3 all use vertical strokes in the Suzhou numeral system, adjustments to these numbers’ standard forms are made whenever they appear consecutively to avoid confusion. In our case, when two “twos” appear consecutively, their form changes to “〢二”: the certificate’s number is 422.

Between reading up on the system and our back and forth quibbles we took a total of thirty minutes to arrive at the answer—but what a satisfying conclusion it was!

*Please note: The overview above is paraphrased from Wikipedia pages on Suzhou numerals, which are below. A link about counting rods (算筹; 算籌), the ancient form of mathematical calculation in East Asia, is also below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suzhou_numerals

https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8B%8F%E5%B7%9E%E7%A0%81%E5%AD%90

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counting_rods

No CommentsVisit the new Chung | Lind Gallery

Posted on May 8, 2024 @1:00 pm by cshriver

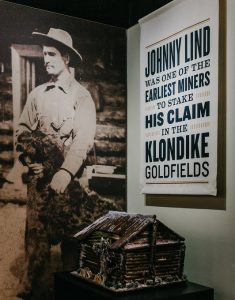

UBC Library is excited to announce the official opening of the Chung | Lind Gallery showcasing the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection and Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection. The new exhibition space in the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre on UBC’s Vancouver campus brings together two library collections of rare and culturally significant materials from Canada’s history.

UBC Library is excited to announce the official opening of the Chung | Lind Gallery showcasing the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection and Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection. The new exhibition space in the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre on UBC’s Vancouver campus brings together two library collections of rare and culturally significant materials from Canada’s history.

Read more about the Chung | Lind Gallery:

- UBC Library opens Chung | Lind Gallery (UBC Library)

- Historic Chinese, Canadian Pacific Railway and Klondike collections unite in new UBC museum (Vancouver Sun)

- UBC gallery offers glimpse of life for early Chinese immigrants (CBC News)

We know that our patrons have missed being able to visit the Chung Collection Room as we have worked to prepare the new gallery. Thank you so much for your patience! We look forward to welcoming you to the new space and also introducing you to the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection for the first time.

We know that our patrons have missed being able to visit the Chung Collection Room as we have worked to prepare the new gallery. Thank you so much for your patience! We look forward to welcoming you to the new space and also introducing you to the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection for the first time.

The Chung | Lind Gallery, on level 2 of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, is open Tuesday-Saturday, 10 am-5 pm. The gallery is free and open to the public, and people of all ages are encouraged to attend. Small group tours and class visits are available by appointment. For more information, please contact (604) 822-3053 or rare.books@ubc.ca.

No CommentsAll About Oscar

Posted on June 27, 2024 @12:56 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Barbara Towell, E-Records Manager with University Archives, for contributing the below post. This exhibit was co-curated by Barbara and RBSC Archivist Krisztina Laszlo.

Artray photo. ([1945]). Oscar outside Oscar’s Steak House at 701 Burrard Street (81420). Vancouver Public Library.

Oscar Blanck (1908-1954) was an entrepreneur, restaurateur and a bon vivant. Born in Brandon Manitoba, he was the eldest son of Jewish immigrants who escaped the antisemitic pogroms in late 19th-century Russia. Details are scant regarding Blanck’s early life except that part of it was spent with his parents and seven siblings in Winnipeg’s north-end known then as “Little Jerusalem”.

In the 1930s Blanck moved west settling in Vancouver with his wife Marjorie Prosterman. According to a 2018 interview with his daughter and UBC alumni Sharon Posner, the Blanck’s first opened a deli on Howe Street, but that venture failed. In 1943 Oscar and Marjorie tried their hand at business again by opening a small grocery and lunch counter called Oscar’s Deli. In the early years they sold groceries, home-made pickles, and sandwiches. This time the Blanck’s business did well enough to expand both their storefront and their menu as adjacent businesses either closed or moved. In just a few years the Blanck’s occupied a commanding spot at 1023 West Georgia and Oscar’s Steakhouse was established.

From Home-made Pickles to Home of the Stars

Westen, E. (1946). [Oscar Blanck tying his necktie] (UL_1622_0063). Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0426628

Oscar had two interconnected goals for his restaurant: to advertise his business by amplifying his image through press coverage; and to cultivate celebrities, which would presumably keep his restaurant full of customers hoping to catch a glimpse of a star. He achieved this objective by knowing what celebrity was in town, enticing them into his restaurant, and photographing the moment for posterity. One of the photographers frequently on-hand was Vancouver Sun photographer, Ralph Bower. Bower said that in the 1950s, Blanck would give him a free steak as payment for a photograph. But Bower was not the only photographer Oscar relied on, Blanck had a handful of photographers he could call at a moment’s notice including: Esther Weston who had a studio at 736 Granville Street, just two blocks from Oscar’s, before moving her business to New Westminster; and former Vancouver Sun photographer, Art Jones who in 1948 started Artray Studios and whose archive of 11,000 photographs was donated to Vancouver Public Library in 1994. If a musical act was playing next door at the Palomar Supper Club, and sleeping at one of the nearby hotels, Oscar endeavoured to ensure they were eating, often gratis, at his Steakhouse!

Jones, A. (c. 1945). [Oscar Blanck with Louis Armstrong] (UL_1622_0034). Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0426654

Explosive Midair Collision

Westen, E. (1946). [Oscar Blanck and a woman] (UL_1622_0074). Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0426628

A memorial service was held for the crash victims in Moose Jaw that was attended by more than 1000 people. Then Provincial Premier, former Baptist Minister, and father of socialized medicine in Canada, Tommy Douglas was the principal speaker followed by various religious personnel (Trotter, 1954). Blanck’s body was returned to Vancouver and buried in the Beth Israel Synagogue in Burnaby, BC.

Aftermath

Blanck’s widow Marjorie Blanck, sued the Canadian Government for $100K in damages which is estimated to be over 1 million dollars when adjusted for inflation. Multiple lawsuits brought by the families of the victims of Trans Canada Airline Flight 9 were eventually settled out of court.

On March 25, 1955, two years after Oscar’s death, Vancouver Sun entertainment reporter, Jack Wasserman had the grim task of reporting the auction results of both the Palomar Supper Club and Oscar’s Steakhouse, two pillars of 1950’s night life in Vancouver. The sale of the lighting fixtures, the name, and the stock of over 1000 celebrity photographs from Oscar’s Steakhouse earned $15,000 for the estate, which is upward of $168,000 in today’s currency.

About the photographs

The photographs in this exhibit are from the Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs donated to Rare Books and Special Collections in 2014 and 2020. Langmann purchased a lot of 146 Oscar Blanck photos locally from Love’s Auction House in the 1960s. The full collection held by UBC Library is digitized and available to view on Open Collections. The photos in this exhibit represent a selection from those held by UBC, and just a tiny slice of the multitude that once lined the walls of Oscar’s Steakhouse, 1023 West Georgia.

All About Oscar is curated by Krisztina Laszlo (Rare Books and Special Collections) and Barbara Towell (University Archives). We were unable to ascertain the names of some of the people in the photographs. Please contact us at rare.books@ubc.ca if you recognise anyone we could not identify.

Works Cited

Ancestry. n.d. “Solomon Blanck.” https://www.ancestry.ca/search/?name=Solomon_Blanck&event=_winnipeg&location=3243&priority=canada (accessed Oct. 9, 2023)

Bank of Canada. n.d. “Inflation Calculator.” https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/ (accessed Oct. 8, 2023)

Bollwitt, Rebecca. 2012 “Vancouver History, Photographer Art Jones.” Miss604. Nov. 7, 2012. https://miss604.com/2012/11/vancouver-history-photographer-art-jones.html (accessed, Oct. 8, 2023)

Cottrell, Alf. 1951. “But Listen.” The Vancouver Daily Province. March 10, 1951. https://www.proquest.com/hnptheprovince/docview/2368740460/B9BD5FA481664AEEPQ/1?accountid=14656 (accessed, Oct 8, 2023)

Donaldson, Jesse. 2019. “The Forgotten Clubs That Brought Vancouver Nights to Life.“ Montecristo Magazine, January 20, 2019, updated May 17, 2021. https://montecristomagazine.com/community/vancouvers-forgotten-nightlife-clubs (accessed Oct. 6, 2023)

Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada. n.d https://www.jhcwc.org/jhc-search-detail/?sid=12912&tp=articles&pg=1 (accessed Oct. 8, 2023)

Mackie, John. “Pavel Bure, Sonny Homer’s red pants, and Ralph Bower.” The Vancouver Sun. Jun 10, 2018. https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/pavel-bure-sonny-homers-red-pants-and-ralph-bower. (accessed Oct. 8, 2023)

Posner, Sharon. 2018. Interview by Debby Frieman. The Scribe: The Journal of Jewish Museum and Archives of British Columbia, Volume 37: 20-24.

Richards, Dal and Jim Taylor. 2009. One More Time: The Dal Richards Story. Harbour Publishing 2009

Trotter, Graham. 1954 “Five Victims of Air Crash Identified.” The Nelson Daily News, April 12, 1954. https://open.library.ubc.ca/viewer/nelsondaily/1.0427552#p0z-2r0f: (accessed Oct 6, 2023)

Vancouver Daily Province. 1948. “Ties and T-bone Steaks Have Made Him Famous.” Dec 11, 1948. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/december-11-1948-page-80/docview/2368956007/se-2. (accessed Oct. 08, 2023)

Vancouver Daily Provence. 1954. “Eyewitness Accounts: TCA Crash Scene Terrible.” April 9, 1954, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/april-9-1954-page-3-44/docview/2369136451/se-2 (accessed October 6, 2023).

Vancouver Daily Province. 1954. “Victim’s Relatives Seek $1,795,000: Families, Estates Sue Crown for Airline Disaster.” Oct 14, 1954.October 14, 1954 (Page 10 of 42) – ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Province – ProQuest (accessed Oct 6, 2023)

Wasserman, Jack. 1955. “About Now.” The Vancouver Sun. Mar 26, 1955, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/march-26-1955-page-29-64/docview/2240206669/se-2 (accessed Oct 8, 2023)

No CommentsLowry Manuscripts (Re)Launch

Posted on January 12, 2024 @4:33 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Malcolm Fish for contributing the below post! Malcolm is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and has just completed a Co-op position with RBSC. He’ll be continuing on with RBSC this term in a Graduate Academic Assistant (GAA) position.

Funding for this project was generously provided by the George Woodcock Canadian Literature and Intellectual Freedom Endowment.

UBC Library Rare Books and Special Collections is pleased to announce the (re)launch of the landmark Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection. One of the largest single collections of Malcolm Lowry records worldwide, UBC has been collecting Lowry materials since the initial deposit of the Malcolm Lowry papers by Lowry’s widow, Margerie Bonner Lowry, in 1961. Since that initial deposit, the collection has grown substantially, now spanning more than six meters of textual records, more than 1000 photographs, and a variety of A/V materials, including a copy of the movie adaptation of Lowry’s seminal novel, Under the Volcano. Now that work assessing and redescribing the Collection is complete, researchers and educators can access and search this incredible collection more effectively than ever.

Summary of Work Completed

The Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection is one of UBC’s oldest keystone research collections. Given the scope of the holdings, any work undertaken to update and improve the collection’s inventory records and access descriptions was going to require substantial time and effort to effect. RBSC was able to acquire funding specifically to undertake an overhaul of the Collection in 2023. I was hired as a Co-op student to inventory, assess, and redescribe the Collection.

Work on the Collection was completed in four stages. First, I completed a full physical inventory of all the Malcolm Lowry materials, and compared this inventory with the existing finding aid for the Collection. During the inventory stage, I also noted any preservation issues for future treatment. Fortunately, I did not find any urgent concerns.

Once I completed the inventory and confirmed the accuracy of the information in the finding aid, I began stage two, which consisted mostly of data entry. The old PDF finding aid predated current archival descriptive standards and the archival database, AtoM (Access to Memory), used by UBC. Useful information (file titles, date ranges, etc.) was taken from that finding aid and entered into AtoM, forming the file-level descriptions now available for easy searching and perusal.During stage three, I focused on increasing intellectual control of the Collection’s many sub-collections. The Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection is comprised of the core Malcolm Lowry Papers and many smaller personal collections donated by or purchased from individuals related to Malcolm Lowry. Many of these smaller collections had previously been considered distinct entities related to the Lowry Papers, but not part of them. At times they were listed twice, once in the old PDF finding aid and also as separate groupings, leading to confusion. I examined each of the sub-collections to determine whether they should be subsumed under the Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection umbrella as a sous-founds (a subdivision of a fonds based on the structure of the creator or the organization of its activity) or maintained as separate, but related materials.

Stage four was reserved for the extensive Photographs sous-fonds. Prior to my work, only about 200 of the more than 1000 photographs in the Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection had been described. Many of the Collection photographs originally came in the form of three photo albums. Previous RBSC staff had removed these photographs from the albums for long-term preservation purposes, but as a result, important contextual information about the order of photographs in the albums was missing. Based on numbered annotations made on the pages of the photograph albums, I added notes about which photographs had come from which albums, and updated the descriptions in the Photographs sous-fonds descriptions. The process was exactly as convoluted as it sounds, but it all led to a significantly expanded set of descriptions of one of the most frequently accessed parts of the Collection.

Once stages one through four were completed, the AtoM record for the Collection was restructured and updated to match the changes described above and descriptions from the collection down to the file and item level were uploaded, resulting in the newly (re)launched Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection page.

Changes to the Collection

The Collection is now organized by creator under the Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection umbrella. For example, the Margerie Lowry collection is now SF02 – Margerie Lowry Papers under the Collection umbrella. Similarly, photographs and microfilm have been given their own sous-fonds for ease of searching. These are SF13 – Photographs and SF14 – Microfilm.

For those familiar with the Collection, a few changes to the descriptions have been made, for example “Papers” is now used instead of “fonds” (e.g., SF03 – Earle Birney Papers, SF04 – Harvey Burt Papers). The Lowry Family fonds is also now also a sous-fonds under the Collection umbrella (SF12 – Lowry Family Papers). In order to maintain the accuracy of citations that refer to the previous descriptions, unique identifiers assigned to each part of the collection have been retained for searching purposes. This will allow all older citation information to remain relevant should new users need to track down a specific source, reference, or citation which predates the relaunch.

Ongoing Work

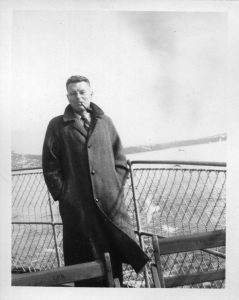

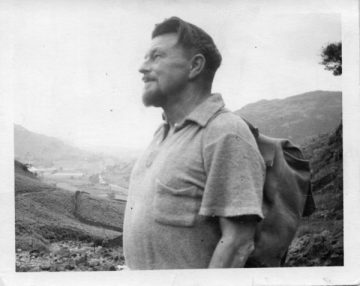

Lowry, Loughrigg How, Lake District. Author’s favorite photograph [p. is cropped with the inscription: Malcolm Lowry, author of Hear Us O Lord From Heaven Thy Dwelling place which will be published by J.B. Lippincott Company]. BC-1614-125

The Malcolm Lowry Manuscripts Collection is one of UBC’s keystone research collections and one of the largest single collections of Malcolm Lowry materials in the world. Researchers and educators frequently come to UBC specifically to access this collection. Overhauling, inventorying, and restructuring the collection has been a satisfying project, which ensures future users are able to effectively search the Collection and find what they are looking for.

No CommentsLangmann Collection selections

Posted on October 4, 2023 @2:46 pm by cshriver

Thanks to Krisztina Laszlo, an archivist with Rare Books and Special Collections for coordinating this exhibition and contributing this blog post!

Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC) is excited to announce a collaborative exhibition of photographs from the Uno Langmann Family Collection of British Columbia Photographs on display across UBC Library branches during the 2023 Fall term. Participating are the Asian Library, Woodward Library, David Lam Library, Koerner Library, Education Library, and the Law Library. The collection, donated by Uno and Dianne Langmann and Uno Langmann Limited, consists of more than 20,000 rare and unique early photographs from the 1850s to the 1970s. It is considered the premiere private collection of early provincial photos, and an important illustrated history of early photographic methods. Like much of the library and archival materials housed at RBSC, the Langmann photographs reflect the history of British Columbia, including its history of colonisation, patriarchy, homophobia, heteronormativity, and racism. These threads are interwoven through the collection, although at the time of creation the photographers meant to celebrate and document the province’s development. A contemporary critical reading of the photographs informed the curation of the overall exhibit. Each library branch selected images to display by reviewing digitised content available on Open Collections, which currently has approximately 7,900 photographs from the Langmann collection digitised and available to the public. Branch curators each selected material according to their individual vision for the exhibit and the themes they wished to address. The selections show not only the breadth of possibilities for critical engagement, and the many ways this material can be used to ask questions about our collective history, but also the incredible scope of the archive itself.

In their own words….

Asian Library

We chose the images here as we felt that these represent pivotal moments for Asian Canadian communities in British Columbia.

Japanese Gate in Torii Style, Hastings St.

This image reflects a community that has been established and is thriving within the city. There are clear signifiers of Japanese culture and tradition, indicating the establishment of Japantown in the area. The image also sparks sadness. Following this era, the area witnessed the forced removal of Japanese Canadian community members resulting from the 1942 internment, and through its location in the heart of the Downtown Eastside, it subsequently transformed into a space of despair for many residents of the area. The Hotel Balmoral, a now-derelict single-room occupancy building that was condemned by the city and is slated for demolition, is depicted here as part of a bright and bustling cityscape, reminding us that since its construction in 1911-1912, the building has been in continuous use to the present day.

Sikh Immigrants, Vancouver, B.C.

This image signifies how not just individuals but communities immigrated to these shores. We see ship, train and carriage transportation and one can really feel the tremendous voyage that the individuals in the picture have already taken to arrive at the port, and the long journey still ahead of them to settle into the city and province. The image was also taken during a time when the Canadian government was actively trying to cut off immigration from those of Sikh faith as well as other Asian migrants, underscoring the resilience of those pictured here.

- Japanese Gate in Torii Style, Hastings St. [between 1850? and 1930?]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1022_0042

- George Barrowclough. Sikh Immigrants, Vancouver, B.C. [between 1910 and 1920?]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0052

Koerner Library

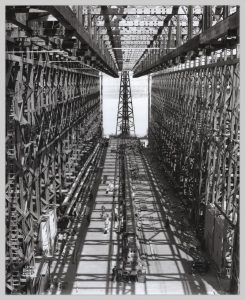

We were interested in selecting images related to labour and workers, since this is a subject area included in the collections at Koerner Library and one that seems topical and timely. There has been much research and discussion recently about workers and jobs in relation to the pandemic, and at the time we were making our selections, union negotiations and strikes were very much in the news. We hope that our specific selections depict a few compelling examples of the breadth of work and industry that has been part of our provincial history, and the workers themselves who have done the labour.

- Going for Peat. c. 1900. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1626_01_0116

- Dominion Photo Co. Ship Building Facility. c.1930. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1604_0167

- Tobacco Farming. c.1915. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1626_01_0199

- Indigenous Women Working with Fishing Nets. c.1920. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1626_01_0199

Woodward Library

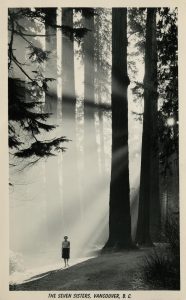

The Seven Sisters

A sacred place. What do these words mean to you?

At one time these trees were the most popular destination in Stanley Park for settlers and other visitors. A trail, created to allow for more visitors, was named Cathedral Trail to acknowledge the experience of standing among these giants of the forest. There was a sense of sacredness, as if standing in a great cathedral.

Too many visitors led to damaged roots, and in the 1950s the unstable trees were felled. New trees now grow in their place, but it remains to be seen if that sacred quality will ever return.

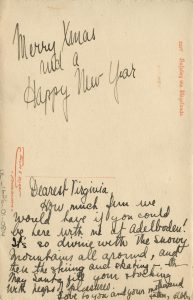

“Guess who this is?”

Libby’s postcard to Virginia from the skiing village of Adelboden, Switzerland teases us with unanswered questions. We see an intrepid adventurer beginning the long hike up to the ski area.

Who is this person?

Is it Libby, her image transposed onto a postcard with the modern equipment of the 1950s? Or a stranger, intended to represent Libby and her adventures at Adelboden? Could it be an acquaintance, known to both Libby and Virginia?

The person seems to be setting out alone, fresh and ready for the long climb ahead – there were no chairlifts in those days. But who is taking the picture?

- The Seven Sisters. c.1940. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0110

- Thor E. Gyger. “Guess who this is?” c.1950. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1626_01_0814

- “Guess who this is?” (verso)

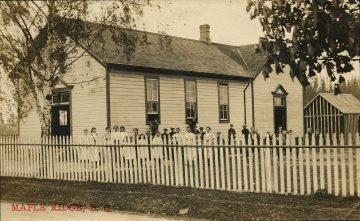

Education Library

Critical Literacy, Learning, and Place:

The Langmann photographs on display at the Education Library were selected to invite a critically literate approach to exploration of the images and how these relate to the history of education in British Columbia. These images, depicting schools and classes in BC between what is estimated to be between 1904 and 1930, invite questions about the intersection of place, time, and learning:

- Who were the teachers and students in the classrooms during this time period?

- Who was not included in these places of learning?

- What kinds of lessons, both explicitly and implicitly, were being taught in these classrooms? How were they being taught?

- What impact did these physical spaces have on the learning that took place within them? What lessons can we learn today about the way that place impacts learning?

We encourage visitors of the Education Library to consider these questions and more as they explore the photographs.

- William T. Cooksley. School House, Maple Ridge. c.1910. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_04_0043

- Public School, Vancouver. c.1915. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_04_0240

- Queen’s Academy, Victoria. c.1905. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0299

- William Brown. Lord Melvin School, New Westminster. c.1905. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0210

The Langmann exhibit photos are outside room 205, in the back left corner of the first floor of the David Lam library

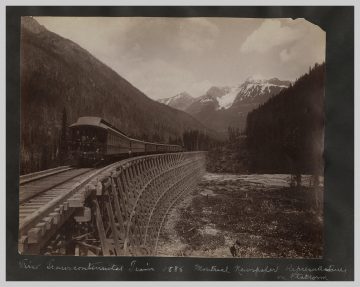

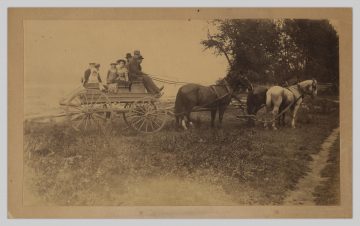

David Lam Library

First Trans-Continental Train

I chose this image as the transcontinental railway was part of the first infrastructure to unite the east and west of Canada – a monumental point in Canadian history in 1885.

Horse and Carriage, Kamloops

This was a public bus in the 19th century. I chose this image to show what public transit was like in BC before the advent of the internal combustion engine – this is the Kamloops to Hope stagecoach line using a four horsepower locomotion: the Barnard Stage in 1885.

- First Trans-Continental Train. 1885. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1475_0014

- Horse and Carriage, Kamloops. 1885. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_2050_0001

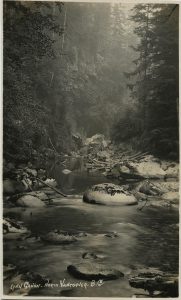

Law Library

We selected the two photos of Lynn Canyon because of the serene natural setting. Both photos provide a perfect parallel to the natural beauty of Pacific Spirit Regional Park that surrounds the UBC Vancouver campus. In addition, the north side of the UBC Law Library provides exceptional views of the North Shore where Lynn Canyon is situated.

- Lynn Canyon, North Vancouver. c.1915. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_04_0204

- George Gordon Nye. Lynn Canyon, North Vancouver. c.1910. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_04_0392

Acknowledgements

This endeavour was truly a group-effort! Thank you to everyone who helped make this multi-branch exhibit possible: Elizabeth Stevenson (Woodward Library), Sally Taylor (Woodward Library), Jacky Lai (Rare Books and Special Collections), Weiyan Yan (Rare Books and Special Collections), Jennifer Orme (David Lam Library), Christina Sylka (David Lam Library), Irena Trebic (David Lam Library), Anne Olsen (Koerner Library), Alex Alisauskas (Koerner Library), Elizabeth Robertson (Co-op Student, Koerner Library), George Tsiakos (Law Library), the team at the Asian Library, Jennifer Fairchild Simms (Education Library), Emily Fornwald (Education Library).

It’s been a pleasure working with all of you.

Krisztina Laszlo, Rare Books and Special Collections Archivist and Project Coordinator

No CommentsHighlighting student work

Posted on September 18, 2023 @10:29 am by cshriver

This summer, RBSC was delighted to host a class from Langara College studying the geography of British Columbia. The course, taught by Professor David Brownstein, included an assignment that tasked students with choosing a digitized archival item, describing what the object means to the regional geography of British Columbia, why is it important, and why they selected it. A few students kindly gave us permission to share their selections on our blog, along with short excerpts from their final assignments. Enjoy!

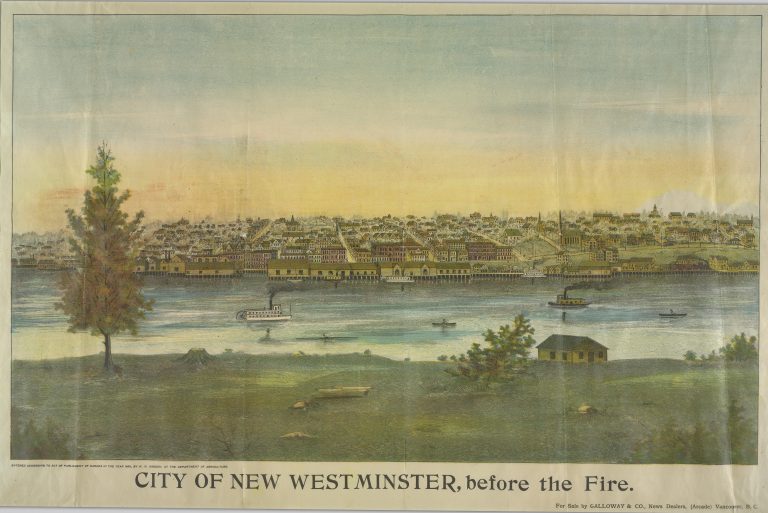

City of New Westminster, before the Fire

Selected by German David Gonzalez

The cause of the [New Westminster] fire remains unknown, but the catastrophe was of such magnitude that an aid committee was formed. The fire motivated the creation of a complete fire brigade and brought touristic growth for the city, which then started receiving more and more visitors who wanted to see with their own eyes how a place that was once devastated, became rebuilt.

Lake District of Southern British Columbia

Selected by Yat Man Lam

The Lake District of Southern British Columbia. Canadian Pacific Railway. The Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC-TX-201-6-2.

This pamphlet featured in its front cover several well-dressed ladies and children enjoying their time in a picturesque countryside, the lake district of southern British Columbia, where there were mountains, trees, rivers, valleys and fields. It was produced by The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1920 as a promotional initiative to attract visitors to the stretch of land between the Prairies of Western Canada and the Pacific Coast… The CPR’s success, achieved through collaboration with the government and resulted in its acquisition of 25 million acres of land (Eagle, 1989[1]), came at the hidden cost of displacing the Indigenous communities.

[1] EAGLE, J. A. (1989). The Canadian Pacific Railway and the Development of Western Canada, 1896-1914. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Indigenous People Catching Salmon

Selected by Jonry Ephraim Isla

Indigenous People catching salmon, Somas River in Vancouver Island. Leonard Frank. Uno Langmann Family Collection of BC Photographs. UL-1550-0002.

Understanding and acknowledging the contributions of Indigenous peoples is essential to grasp the historical and cultural significance of their presence in British Columbia’s fishing industry. With their deep-rooted connection to the ocean and its resources, Indigenous communities have practiced fishing for thousands of years, playing a vital role in shaping the fishing industry in the region. Their traditional knowledge and sustainable fishing practices have been integral to the development of the salmon business in BC. Figure 1 shows a rare photograph taken in 1910 by Leonard Frank, a German-Canadian photographer, which presents two Indigenous men actively fishing for salmon. While Leonard Frank gained fame for his extensive collection of photos, predominantly centered around industrial advancements and city life, he also captured moments of Indigenous life, making their activities part of his photographic legacy.

No CommentsLessons from the Archives Collective

Posted on September 1, 2023 @9:50 am by cshriver

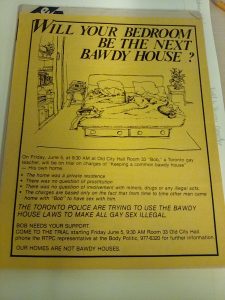

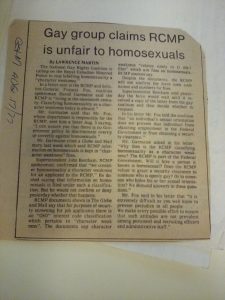

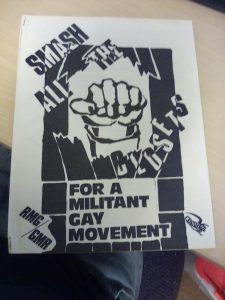

Content warning: The following blog post discusses homophobic attitudes and laws in a historical context.

Many thanks to guest blogger Matthew White for contributing the below post! Matthew is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and has completed both a Co-op position and a Graduate Academic Assistant (GAA) position with RBSC.

This is part of an ongoing series of blog posts that gives students and RBSC team members a chance to show off some of the intriguing materials they encounter serendipitously through their work at RBSC.

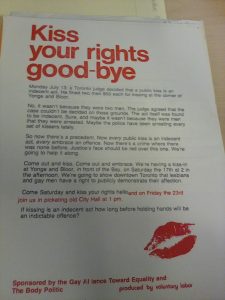

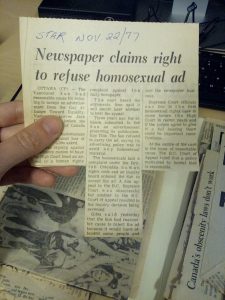

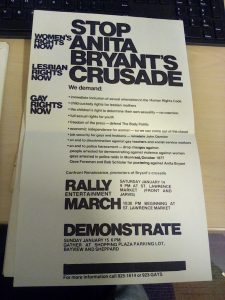

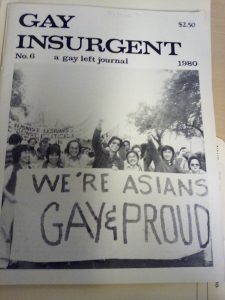

As a queer man, it was with a great deal of excitement that I was asked to finalize the processing of the Archives Collective collection at Rare Books and Special Collections. The Archives Collective, a predecessor of both ArQuives (formerly Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, and Canadian Gay Archives) as well as the BC Gay and Lesbian Archives, collected widely over their short tenure, much of it related to the deeply political lives of gay men and women in the 70s and 80s.

This collection was at times gut-wrenching in the displays of homophobia, at times brought me to tears because of the solidarity between marginalized communities. There were some consistent themes throughout the collection that I would like to share, particularly as they relate to queer lives in the world today.

The first thing I want to stress is that the RCMP and the Canadian legal system have never been friends to queer people, not to mention working people, women, First Nations, and immigrants. They will uphold whatever laws are in the books – if these laws discriminate against gays, so be it. The number of times that the RCMP overstepped by entrapping gay men having sex in their own homes, by keeping files on notable queer activists as potential enemies of the state, not to mention NDP leaders, prominent feminists or Indigenous activists, by physically accosting queers in the streets was staggering.

Obviously, queers did not go down without a fight – a fight that we are still fighting to this day. Gay militancy spread rapidly, with groups like the Lavender Panthers prowling streets to protect queer people. Protests were staged rapidly, and long running education or legal campaigns were effective in bringing these issues into the public eye.

It was not difficult, though, to see how these kinds of attitudes were maintained for so long. One pamphlet by the League Against Homosexuals (LAH) said, “Queers exist to seduce and pervert our children. Queers are sexually depraved vampires. If queers are allowed to have “equal rights” then they MUST be allowed to seduce your child.” I am still confused as to why equality necessitates molestation, but this was perhaps only the most glaring example. The Toronto Star and the Vancouver Sun often refused to advertise for gay magazines, leading to a legal battle by the Vancouver Sun in the mid-70s that they won in the Supreme Court of Canada. It was noted that it might offend readership, so it did not have to be included.

An article in an unknown newspaper by McKenzie Porter notes “Many homosexuals are no longer satisfied with acceptance, sympathy and freedom from prosecution. They now seek approval acclaim and authority. The propaganda of homophile associations both female and male, reveals undisguised aspirations to political leadership.” Porter goes on to say that gay men and women are unfit for politics because of “a neurotic or psychotic state of paranoia associated, for reasons unknown, with a childhood history of anal eroticism.”

The Star, after being accused of homophobia, made the following statement: “… we stop short of encouraging the spread of homosexuality. We have no wish to aid the aggressive recruitment propaganda in which certain homosexual groups are engaged, and we strongly oppose those who seek to justify and legitimize homosexual relations between adults and children.” Like current legal oppression against trans people, children were often the basis of homophobic attacks. Other examples include a well-documented campaign by Anita Bryant to halt the gay liberation movement, by using children’s safety and wellbeing as the basis of her homophobia.

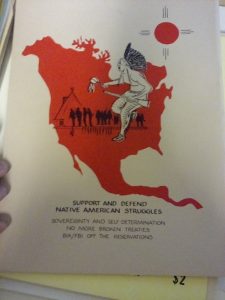

It was this kind of push back that brought gay people back onto the street, time and time again. It was a dynamic period, full of fundraising dances, highly publicized legal battles, and periodicals that discussed gay issues – anything from criticism of Marxist attitudes towards homosexuality to letters of support by brothers and mothers to their trans daughters, from rallies against racial discrimination experienced by taxi drivers, to graphics protesting the treatment of Indigenous peoples across North America.

You’ll also note the absence of trans people in my descriptions of the archive – they are, unfortunately, notably absent. Then, as now, often trans people found difficulty finding welcoming environments, and focus on liberation was often focused exclusively on sexuality without engaging critically with transgender or transsexual issues.

For myself, as an aspiring archivist and as a gay man, this was an incredibly enlightening experience. Many queer people have noted the generational absences that exist in our communities due to AIDS and other issues, including suicide and the return to the closet that can occur as queer people age. Being able to access so much of the knowledge and experience of queer people through the archive feels so important. These were people who knew what needed to be done to enact change, and all of that information is still at our fingertips. If we can’t talk to our queer ancestors, then maybe we can learn from what they left behind.

No CommentsChung Translation Project: Chinese Miners in BC

Posted on August 15, 2023 @4:31 pm by Claire Malek

Dr. Weiyan (Vivian) Yan works as an Office, Copying & Shelving Assistant at the Rare Books and Special Collections Library at the University of British Columbia. She has recently been translating descriptions of the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection from English into Chinese. During this work, she highlighted a few interesting materials for the RBSC Blog. Thank you, Vivian!

This image shows how to switch between English and Chinese language descriptions in the archival database

Chinese Miners in 19th Century British Columbia

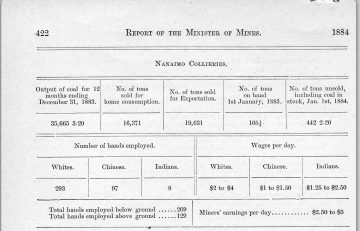

Item Title: Report of the Minister of Mines

Description: A report of the Minister of Mines on the mining accident of 1883.

Item Number: RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-TX-100-43-5

Chinese description: https://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/report-of-the-minister-of-mines?sf_culture=zh

English description: https://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/report-of-the-minister-of-mines?sf_culture=en

View digital item online: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/chung/chungtext/items/1.0356535?o=0

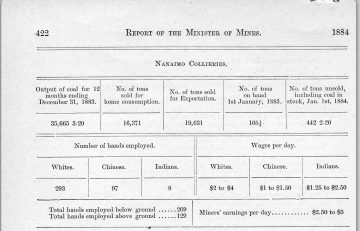

The report states that in the year of 1883 alone, there were 28 mining accidents. Of these, 12 accidents involved Chinese people, accounting for 42.9% of the total number accidents. One of the miners died, and another 11 were injured.

The report also indicates that in 1883, Nanaimo Collieries employed a total of 398 miners. Among them are 97 Chinese people, accounting for 24.4% of the total number of miners. We can also see that the salary of white people is $2-4 per day, the salary of Chinese people is $1-1.5 per day, and the salary of Indigenous People is $1.25-2.5 per day.

In Wellington Collieries, a total of 559 miners were employed in 1883. Among them are 276 Chinese, accounting for 49.4% of the total number of miners. Here, the wages of white people were $2-3.75 per day, and the salary of Chinese people were $1-1.25 per day.

A close up of the Report of the Minister of Mines showing the wages of white and racialized miners.

The report starkly demonstrates the living conditions of the Chinese people at that time. In an environment of discrimination, they did the most dangerous jobs, and were rewarded with the lowest pay.

This blog post is also available in Chinese here.

No Comments蔣氏珍藏系列之一:1883年BC省的中國礦工

Posted on August 24, 2023 @1:17 pm by Claire Malek

閆維艷博士是不列顛哥倫比亞大學圖書館善本特藏部的圖書館助理。她最近致力於將蔣氏珍藏的部分內容翻譯成中文。在這項工作中,她特別介紹了一些珍貴有趣的藏品。謝謝你,維艷!

該視頻教您如何在檔案數據庫中切換中英文內容

蔣氏珍藏系列之一:1883年BC省的中國礦工

中文说明: https://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/report-of-the-minister-of-mines?sf_culture=zh

中文說明: https://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/report-of-the-minister-of-mines?sf_culture=en

在线查阅开放数据库: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/chung/chungtext/items/1.0356535?o=0

編號為RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-TX-100-43-5 的收藏品,名為Report of the Minister of Mines,是一份礦業部長關於1883年採礦業事故的報告。

報告指出,僅此一年,共發生28起事故。有12起事故為中國人,佔比為42.9%。其中一人死亡,11人受傷。

這份報告還指出,在1883年,Nanaimo Collieries共僱傭礦工398人。其中有97名中國人,佔礦工總人數的24.4%。白人的薪資為每天$2-4,中國人的薪資為每天$1-1.5,而原住民的薪資為每天$1.25-2.50。

在Wellington Collieries,1883年共僱傭礦工559人。其中有276名中國人,佔礦工總人數的49.4%。白人的薪資為每天$2-3.75,中國人的薪資為每天$1-1.25。

從這份報告可以反應華人當時的生存狀況。在被歧視的環境中,他們幹最危險的工作,拿最低的薪酬。

矿业部长报告显示了白人和少数族裔矿工的工资差别。

矿业部长报告的特写显示了白人和少数族裔矿工的工资。

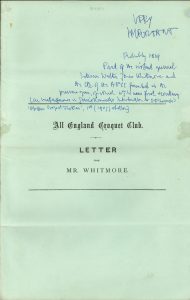

A croquet scandal!

Posted on August 11, 2023 @2:19 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Atreya Madrone for contributing the below post! Atreya is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and is completing a professional experience with RBSC this summer working with vertical files, which are individual or small groups of archival materials.

This is part of an ongoing series of blog posts that gives students and RBSC team members a chance to show off some of the intriguing materials they encounter serendipitously through their work at RBSC.

This summer I am undergoing a Professional Experience working with the vertical files at Rare Books and Special Collections.

Within the vertical files, I found an open letter to the All England Croquet Club written by their Honorary Secretary Walter Whitmore in the 1860s or ‘70s. Whitmore is responding to charges other members of the Club brought against him, including falsifying meeting minutes to make himself look better. This letter is so funny! Who knew croquet could be so scandalous. Check out the Tremaine Arkley Croquet Collection for other croquet materials here at RBSC.