A croquet scandal!

Posted on August 11, 2023 @2:19 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Atreya Madrone for contributing the below post! Atreya is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and is completing a professional experience with RBSC this summer working with vertical files, which are individual or small groups of archival materials.

This is part of an ongoing series of blog posts that gives students and RBSC team members a chance to show off some of the intriguing materials they encounter serendipitously through their work at RBSC.

This summer I am undergoing a Professional Experience working with the vertical files at Rare Books and Special Collections.

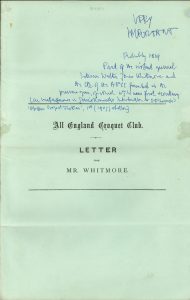

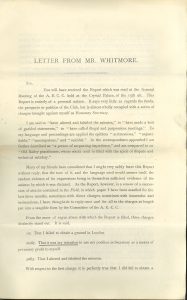

Within the vertical files, I found an open letter to the All England Croquet Club written by their Honorary Secretary Walter Whitmore in the 1860s or ‘70s. Whitmore is responding to charges other members of the Club brought against him, including falsifying meeting minutes to make himself look better. This letter is so funny! Who knew croquet could be so scandalous. Check out the Tremaine Arkley Croquet Collection for other croquet materials here at RBSC.

Posted in Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Research and learning | Tagged with serendipity

During Pride, reflecting on ASK

Posted on June 30, 2023 @3:23 pm by cshriver

Content warning: The following blog post includes mention of suicide and refers to homophobic and transphobic policies and laws in a historical context.

Many thanks to guest blogger Atreya Madrone for contributing the below post! Atreya is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and is completing a professional experience with RBSC this summer working with vertical files, which are individual or small groups of archival materials.

This is part of an ongoing series of blog posts that gives students and RBSC team members a chance to show off some of the intriguing materials they encounter serendipitously through their work at RBSC.

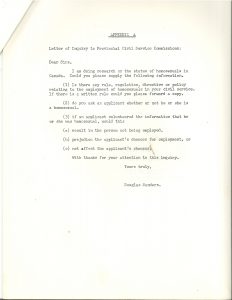

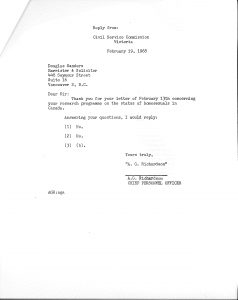

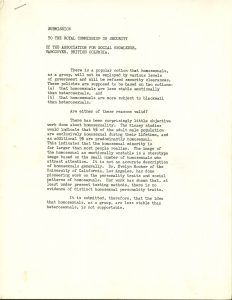

This summer at RBSC I am working with the vertical files for a professional experience project and I have found some extremely interesting materials. At the end of Pride month, I came across a submission to the Canadian Royal Commission on Security from the Association of Social Knowledge (ASK), the first gay rights group in Canada.

Within the file is a study conducted by the group where they sent out letters to government organizations with a brief questionnaire regarding the hiring of queer employees and the responses received from all across the country. Also included in the file is a detailed list of court cases against queer and trans people in Canada. One such court case occurred in Vancouver where police trapped 5 people in a bathroom in Stanley Park and ASK states that “there were suicides as a result of this police surveillance.” These court cases occurred in July 1963, 60 years ago almost exactly. The materials in this vertical file gives us primary source material on anti-queer and trans sentiments within Canada and reminds us that Pride is about protecting queer and trans people and fighting systemic queer and transphobia.

Posted in Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Research and learning | Tagged with

“Vertical files” and witch trials

Posted on June 23, 2023 @12:40 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Atreya Madrone for contributing the below post! Atreya is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and is completing a professional experience with RBSC this summer working with vertical files, which are individual or small groups of archival materials.

This is part of an ongoing series of blog posts that gives students and RBSC team members a chance to show off some of the intriguing materials they encounter serendipitously through their work at RBSC.

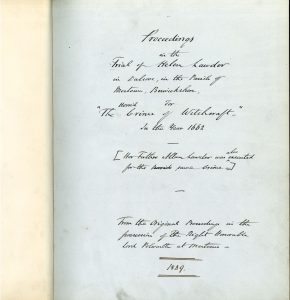

This summer I am undergoing a Professional Experience working with the vertical files at Rare Books and Special Collections. There is a wide range of things to be found in the vertical files, including a copy of Helen Lawder’s witchcraft trial from 1662, which was transcribed in the early 1800s. Lawder was convicted of that “horrid, abominable, and damnable crime” and was to be “strangled at the stake till she was dead and then her body to be burned to ashes.” Myself and other student workers had never seen an actual trial proceeding for witchcraft, so it was a fascinating read – there are many wild details, so come by and read it yourself!

This summer I am undergoing a Professional Experience working with the vertical files at Rare Books and Special Collections. There is a wide range of things to be found in the vertical files, including a copy of Helen Lawder’s witchcraft trial from 1662, which was transcribed in the early 1800s. Lawder was convicted of that “horrid, abominable, and damnable crime” and was to be “strangled at the stake till she was dead and then her body to be burned to ashes.” Myself and other student workers had never seen an actual trial proceeding for witchcraft, so it was a fascinating read – there are many wild details, so come by and read it yourself!

Posted in Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Research and learning, Uncategorized | Tagged with serendipity

“Like stepping into a person’s shoes”

Posted on April 19, 2023 @10:58 am by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Marion Arnott for contributing the below post! Marion is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and just completed a Work Learn position as a student archivist with RBSC.

What do a politician, a nurse, a road construction engineer, an exotic dancer, and a poet have in common? The records and materials of these interesting and diverse individuals can all be found at Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC). As my Work Learn position at RBSC comes to a close, I reflect on the variety of projects, materials and subjects I had the privilege of working on during my time here. The practical experience and exposure to archival work that I gained while working at RBSC has been invaluable to my own learning as an emerging archival professional and student at UBC’s iSchool.

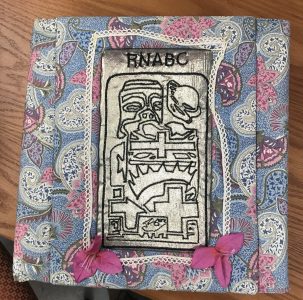

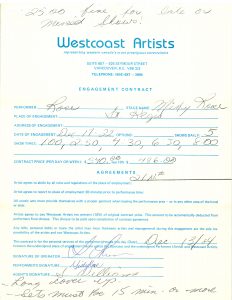

A common thread that I noticed while processing materials, and in conversations with colleagues, is the inclusion and elevation of women’s voices in the historical record preserved by RBSC. In January 2022, I completed a Co-op position at RBSC where I integrated the records of the British Columbia History of Nursing Society (BCHNS) Archives into RBSC’s holdings. Since that time, BCHNS had donated additional materials which I got to process as a Work Learn student. It was fun to see familiar names and faces of the nurses in the records and photographs. The origins of nursing in BC represents women emerging into professional careers and taking on leadership roles within healthcare and the community. As I arranged and described the Society’s records, which contain numerous biographical files of notable individuals who made outstanding contributions to the profession, I was amazed at the strength and persistence of these women despite countless barriers. The records bear witness to not only the history of the profession but also the community that developed among individuals through nursing schools, committee work, community advocacy, and professional associations. I especially enjoyed finding the scrapbook of photographs and materials compiled by the Richmond-Delta Professional Practice Group a sub-committee of the Registered Nurses Association of British Columbia (RNABC) in honor of the RNABC’s 75th Anniversary. The album is protected by a beautifully quilted fabric cover, which I feel demonstrates the care and commitment of these women to preserve and present the history of nursing in the province. Contained inside are photographs, notecards, invitations and other related materials of events, ceremonies, fashion shows, workshops, and other occasions that reveal a small slice of the extensive work of these women.Another women I encountered in my work here, was Rose Amann also known by the stage name Misty Rose. Amann donated a small collection of materials to RBSC which document her career as an exotic dancer in Vancouver’s burlesque and night club scene. While the records are predominately hotel and agency contracts, it was Amann’s biography that captured my attention. Her journey to becoming a dancer was so engrossing and filled with persistent determination for a career built on a personal interest and love of dance. Misty Rose’s life provides a glimpse into the history of Vancouver’s entertainment industry while also highlighting a very unique perspective not well documented in the archival record. Her biographical sketch provides extensive context to the physical materials.

It is these records and individuals that provide insights into the past in rather unusual ways that attracts me to archival work. Processing archival materials is a bit like stepping into a person’s shoes temporarily and experiencing their life through the records they create and receive. Overall, my time at RBSC has been filled with discovery and learning, and the projects I worked on only represent a small portion of the amazing materials and stories that can be explored in RBSC’s holdings.

No CommentsPosted in Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Research and learning | Tagged with

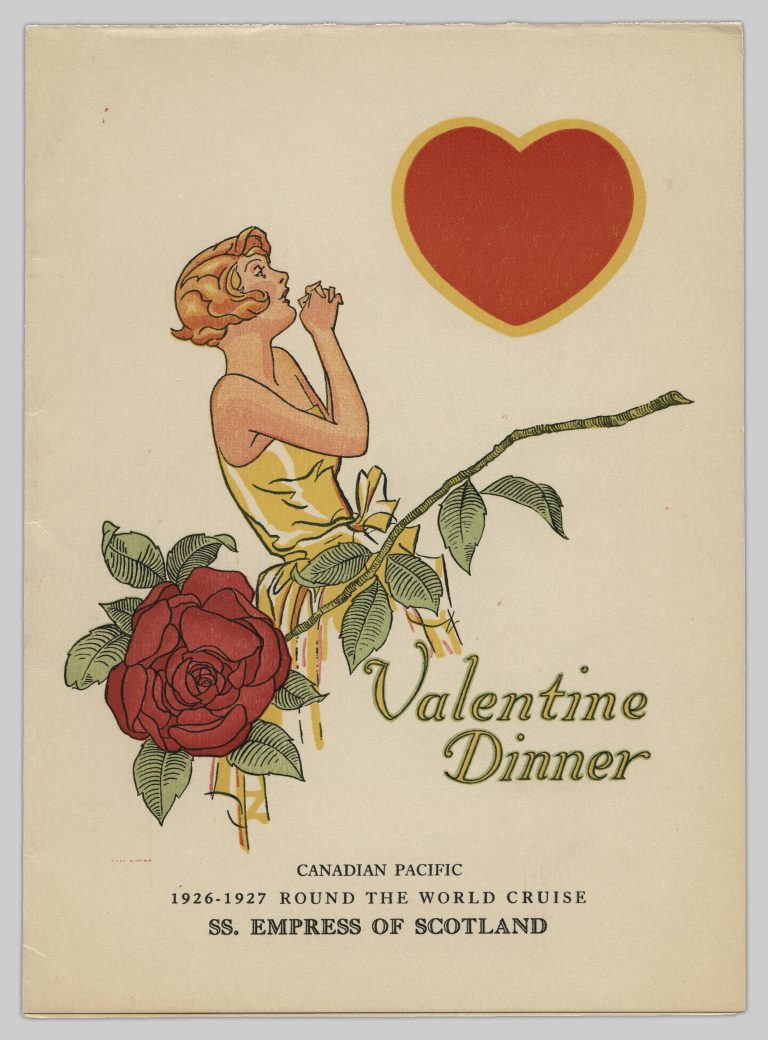

A valentine from RBSC

Posted on February 8, 2023 @4:24 pm by cshriver

In honour of Valentine’s Day, a poetic interlude from one of RBSC’s archivists, Krisztina Laszlo.

Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

We have some romantic archives for you!

To celebrate St. Valentine’s Day this year, please enjoy a few selections from our collections.

- [Chinese wedding portrait]. The Chung Collection. CC-PH-00331

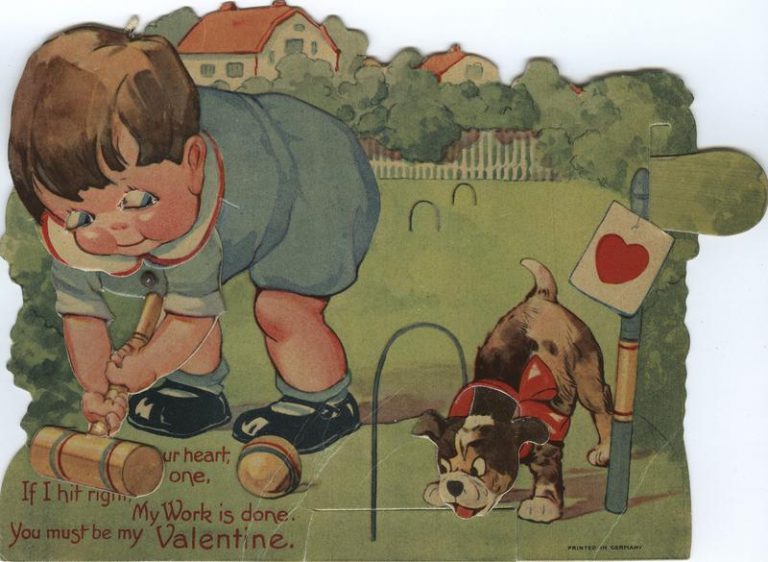

- Valentine, c.1919. Tremaine Arkley Croquet Collection. Croquet-Box6-0015

- Mr. and Mrs. Kantaro Kadota, 60th wedding anniversary, Vancouver, B.C. Japanese Canadian Photograph Collection. JCPC-25-125

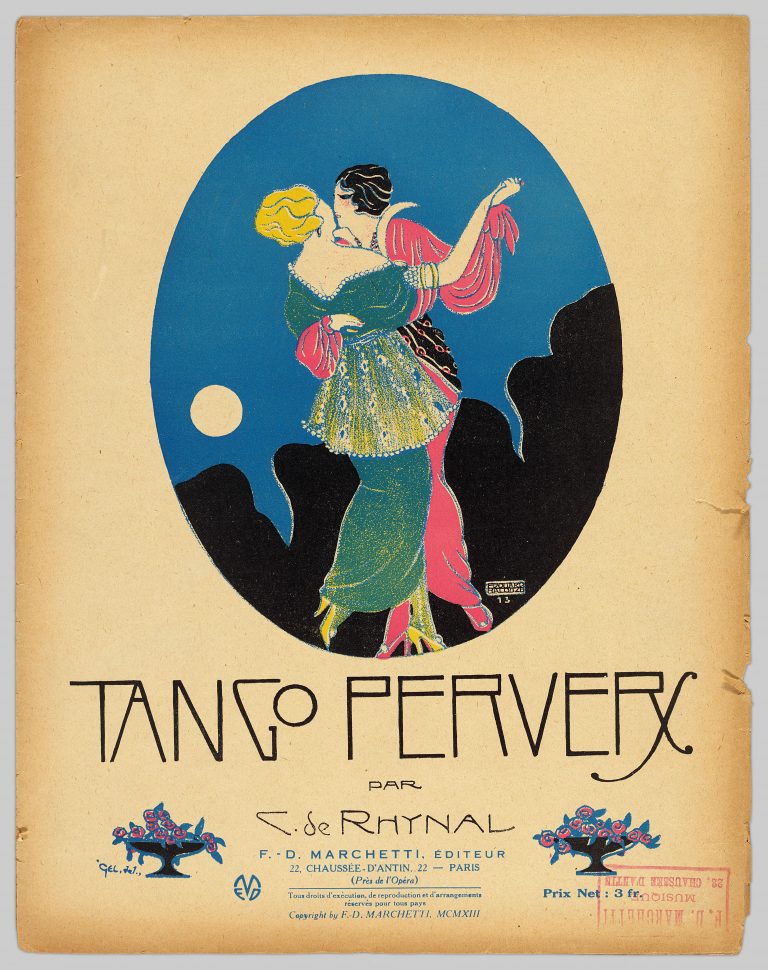

- Tango pervers. spam941B

- [Wedding portrait of Yip Him and Lee Lawn Fan]. The Chung Collection. CC-PH-10676

- Menu from the Valentine dinner on the Empress of Scotland’s 1926-1927 world cruise. The Chung Collection. CC-TX-246-5-12

Posted in Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition | Tagged with

Reading Room Closed

Posted on January 3, 2023 @11:34 am by cshriver

Rare Books and Special Collections and University Archives Reading Room closed through January 31, 2023

The Rare Books and Special Collections and University Archives reading room will be temporarily closed through January 31, 2023 for upgrades.

To accommodate these upgrades, there will be some changes to library services. RBSC and UA will provide some reproduction services and digital instructional support during this time. Some collections maybe be inaccessible until March 2023.

Please contact Rare Book and Special Collections or University Archives for more information on supports available for remote research and instructional support requests. You can also contact specific members of the RBSC team.

Thank you so much for your patience and support during these necessary upgrades!

No CommentsPosted in Announcements, News, Services | Tagged with

Season’s greetings from RBSC!

Posted on December 21, 2022 @10:26 am by cshriver

Happy holidays from the RBSC family to yours!

Just a reminder that Rare Books and Special Collections be closed Monday, December 26; Tuesday, December 27; and Monday, January 2.

RBSC’s offices will reopen on Tuesday, January 3, but our reading room will remain closed through January 31, 2023 for upgrades.

During the reading room closure in January, RBSC and UA will be able to provide some reproduction services and remote research support. Please contact Rare Book and Special Collections or University Archives for more information. You can also contact specific members of the RBSC team.

Thank you so much for your patience and support over the past year during these necessary upgrades!

No CommentsPosted in Announcements, News, Services | Tagged with

“They also serve:” Honouring Alexis Alvey

Posted on November 1, 2022 @9:38 am by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger James Goldie for contributing the below post! James was formerly a student archivist with Rare Books and Special Collections and is now Records and Privacy Analyst with Douglas College. This encore blog post was first published in 2019.

“They also serve:” A. Alexis Alvey and the navy’s first female service members

Unit Officer A. Alexis Alvey of the W.R.C.N.S.

Her mother calls her “the Canadian lieutenant” and the girls in the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service call her “Chiefie”…

So begins a 1943 Royal Canadian Navy press release announcing the promotion of Lieutenant Amelia Alexis Alvey to Unit Officer at H.M.C.S. Stadacona, a rank equivalent to that of an army captain. This new position – granted just a year after she first enlisted – meant Alvey was in charge of more than 1,100 Halifax-based service members from the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS), known as Wrens. More than a third of all Wrens were stationed at H.M.C.S. Stadacona in Halifax.

Alvey (who went by A. Alexis Alvey) was born November 22, 1903 in Seattle, Washington. After completing her undergraduate studies in New York, Alvey studied science at McMaster University (1932-1933) and went on to work as chief photographic technician at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine. It was during this period she gained Canadian citizenship. After the outbreak of World War II, Alvey helped organize the businesswomen’s company of the Toronto Red Cross Transport Corps and commanded it for two years. She had also served as lecturer to the entire Transport Corps for Military Law, Map Reading, and Military and Naval Insignia.

Recruitment advertisements ran in magazines throughout Canada from 1942-1944, reminding readers that women could now serve in the navy as part of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service.

Men Can’t Do It Alone

In 1942, top brass in the Canadian navy realized they could not solely rely on men in their fight against Hitler’s forces. They contacted the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) in London requesting assistance in the formation of a Canadian counterpart. “Please send us a Mother Wren,” they said, according to Alvey. Those “mother wrens” were Joan Carpenter and Dorothy Isherwood, who came to Canada and established the WRCNS later that year. Alvey was among the first to enlist.

Until then, the Canadian navy had been an all-male service. As one member wrote in 1943: until the establishment of the WRCNS, “ships and shore establishments alike were manned by men, and knitting seamen’s stockings, or collecting magazines, games and special parcels for ships’ crews at sea was about the limit of any contribution made by women.”

Women were not permitted to serve in combat roles, however, they took over the navy’s on-land operations, which freed up male service members to join battles at sea. The Wrens worked as signallers, wireless-telegraphers, writers, information and intelligence workers, postal clerks, research assistants, cooks, stewards, wardroom attendants, laundry assistants, and more.

Rising Through The Ranks

A. Alexis Alvey (far right) with fellow “Wrens” at the W.R.C.N.S. training centre in Galt, Ontario.

In her first year with the WRCNS Alvey was appointed acting Chief Petty Officer Master-at-Arms. Her other assignments included duty as Deputy Unit Officer H.M.C.S. Bytown (Ottawa), duty with the Commanding Officer Pacific Coast H.M.C.S. Burrard (Vancouver), assignment as Unit Officer, Lieutenant H.M.C.S. Bytown, and finally Unit Officer to H.M.C.S. Stadacona (Halifax). She was responsible for training and running practice drills, developing policies, and meeting with officers from ships that arrived in Halifax.

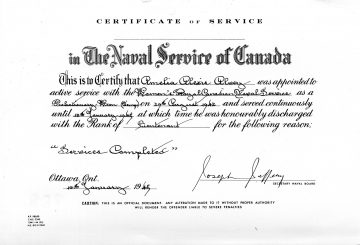

She served with the WRCNS from August 1942 to January 1945.

The A. Alexis Alvey Fonds

After the war, Alvey returned to her home city of Seattle where she worked as a librarian at the University of Washington. However, she never forgot her time with the WRCNS. For the rest of her life, Alvey organized and attended Wrens reunions, she wrote articles and histories about the service, and collected all manner of documents, memorabilia, and ephemera related to the “The Women’s Navy” as it was sometimes called.

The Royal Canadian Navy’s certificates of service were designed with only male service members in mind.

These records along with Alvey’s personal papers and an extensive collection of photographs are housed at UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections and are available for research.

The materials that make up the A. Alexis Alvey fonds express the profound sense of pride shared by Alvey and her fellow Wrens with respect to their years of military service. An essay commemorating the WRCNS silver anniversary by Isabelle NcNair (née Archer) captures this pride. In it, a grandmother tells her granddaughter the story of the Wrens. “But Grannie, I thought Grandad won the war,” asks the child. “No dear,” responds her elder, “I did.”

No CommentsPosted in Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Research and learning | Tagged with

Wish You Were Here?

Posted on August 17, 2022 @4:05 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Gabriella Cigarroa for contributing the below post! Gabriella is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and completed a professional experience with RBSC this summer.

From the Langmann Collection: Early 20th-Century Postcards Depicting Disasters and Accidents

This summer, I completed a Professional Experience at RBSC to assist with cataloguing unprocessed materials. I wanted to work with RBSC to learn more about how special collections document the community they serve. At first, I catalogued posters, broadsides, prints, and other kinds of items that documented B.C. history. A few weeks in, I was offered another project: writing about the Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. I worked specifically with the digital collection, a subset of the larger collection of more than 18,000 photographs that documents B.C. from the 1850s to 1970s.

In the Langmann collection, I encountered many postcards whose picture sides captured disasters and accidents. Postcards today generally feature scenes more appealing to tourists, often picturesque landscapes or buildings. While postcards of this type are present in the Langmann collection, there are also plenty with more unexpected subjects—including that of disasters and accidents. Why was this subject matter chosen as a relatively common subject of photography for postcards, to be sent as correspondence? And what about the format of a postcard is different today from a hundred years ago such that these postcards’ imagery surprised me?

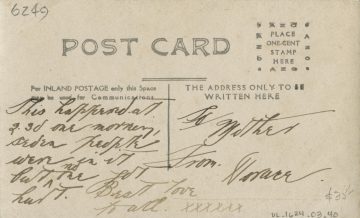

Two postcards first caught my eye, illustrating the contrast between friendly personal correspondence and an image of a disaster or accident. The first, titled A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. car, Vancouver, B.C., features a photograph of a streetcar crash’s aftermath. The photographer is positioned inside the wrecked building, framing the streetcar with the storefront’s windows. Inside the building, debris is piled haphazardly on the windowsill. A group of children smiles, looking in the window of the presumed storefront, maybe even noticing the photographer inside. On the postcard’s back, the sender, Horace, writes to his mother: “This happened at 2.30 one morning, seven people were in it but no one got hurt. Best love to all.” I questioned, why did Horace send this photo and information to his mother?

- Barrowclough, G. A. (1910). A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. car, Vancouver, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0040) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361427

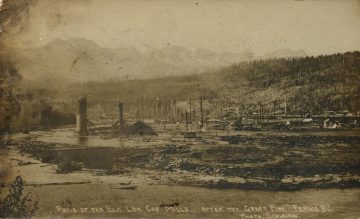

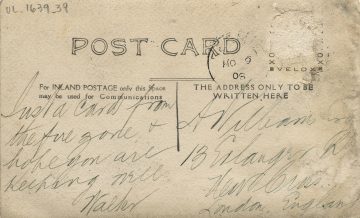

The other postcard presents a picture taken after a fire in Fernie, B.C. In the photographed landscape, few buildings remain intact. Some smokestacks rise from the rubble, while burnt-out husks of trees stretch into the distance. I was struck by the casual language on the postcard’s back, as a man named Walter writes to someone in England: “Just a card from the fire zone + hope you are keeping well.”

- Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

I took a step back to consider the context of these postcards’ creation. As briefly discussed earlier, the purpose of a postcard today is different from that of the other materials I catalogued this summer. The materials outside of the Langmann collection—posters, prints, broadsides, and so forth—were generally created with a broad audience in mind. Postcards, however, are often for personal correspondence. Today, this difference in audience would typically mean a major difference in subject matter. Usually, a person today would want to show a loved one picturesque landscapes, not tragic news relevant primarily to their neighbouring residents. Was this different a hundred years ago?

- Armitage, S. J. (1908). Fernie, B.C., After the Fire of Aug. 1st. 1908 (UL_1639_0003) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371490

- Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

The postcards I selected are roughly from between 1905-1915. It turns out that this period was in the midst of a postcard craze, in which an estimated one billion postcards were created each year in North America (Photo Postcards, n.d.). About ten percent of these postcards were real-photo postcards—silver-gelatin photographs made either as one-offs or in small numbers. In 1903, Kodak had created the A3 camera and an accompanying photograph development kit that allowed anyone to produce a silver-gelatin photograph on postcard paper (Photo Postcards, n.d.). This technological development that allowed increasingly portable and cheap photography, alongside an inexpensive postal system, encouraged layperson photographers to ply their trade. This real-photo postcard craze lasted from 1905 to 1930, although the process was still used into the 1950s (Photo Postcards, n.d.), permitting anyone with such a camera to make a postcard.

Most photo postcards in the Langmann collection are taken by photographic printing companies or unknown photographers. However, the photo postcards I found depicting disasters and accidents were mostly created by individual photographers or unknown individuals. Since anyone with a postcard camera could take postcard photos, the postcards without credit on them could be by anyone, including their senders. Alongside individuals taking their own photos, the postcard camera allowed for a rise in amateur photographers and photography studios.

The photo postcards in the Langmann collection featuring disasters and accidents seem to be created by a few identifiable photographers: Joseph Frederick Spalding, Rosetti Studios, and George Alfred Barrowclough. All three photographed more than the disasters and accidents I initially encountered. Joseph F. Spalding is known for documenting the history of Fernie, B.C., especially the reconstruction after the fire in 1908 (Joseph Frederick Spalding, 2006). Rosetti Studios was run by Lionel Haweis, who is best known for his series of photographs recording the development of Stanley Park (Rosetti Studios – Stanley Park Collection, n.d.). Lastly, Barrowclough is now seen as more of a photojournalist (for a more in-depth discussion of Barrowclough’s work, see my colleague Brandon Leung’s blog post). These photographers chose what they thought should be documented history, and even reproduced as postcards. Whether amateur photographers, commercial studios, or people who happened to own a postcard camera, they all captured what they likely considered significant contemporary events.

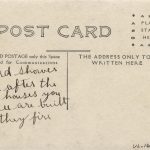

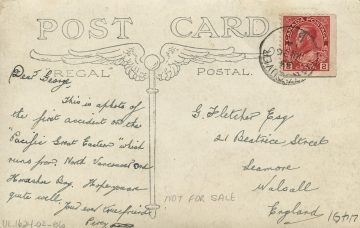

With some postcards, the disasters and accidents were likely considered one type of an event to record, and even to share with loved ones as news. For example, the postcard of the Fernie fire zone discussed earlier is one in a series documenting the town’s recovery and reconstruction (Joseph Frederick Spalding, 2006). Someone sending such postcards as correspondence could discuss the progress of Fernie’s recovery. In the case of other postcards, context concerning the senders’ intentions can be derived from reading the postcards’ letter component. We can look at [View of the Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.]. In the photograph, a train car lies on its side next to train tracks. A couple of people view the train car while others walk by. The back reads: “This is a photo of the first accident on the ‘Pacific Great Eastern’ which runs from North Vancouver and Horseshoe Bay.” The sender provides the context of the Pacific Great Eastern and describes its historical import as the railway’s first accident, marking it as a notable event.

- [unknown]. (1914). [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.] (UL_1624_02_0086) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0360930

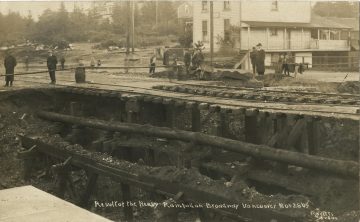

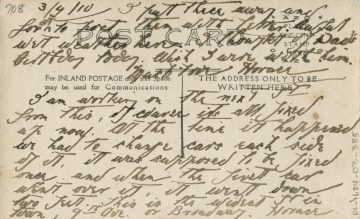

However, this kind of proto-, personal photojournalism is not the only reason for sending these types of postcards. Some postcards seem to be parts of bigger conversations held outside of a single letter. The postcard featuring the fire zone at Fernie is one example, as the recipient would be able to identify the unnamed “fire zone” mentioned in the letter without context from outside the single postcard. Another is the Result of the Heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09. The photograph displays a street in the aftermath of the rainfall, with a large pit and metal structures where the street should be. A set of tracks still runs over the pit. A few people on the side of the pit opposite the photographer look on. On the back of the postcard, a man named Horace writes, “This is next to where I’m working.” He describes not only the event of the crash, but how it interacts with other aspects of the city like the “awful wet weather,” as well as how the event affected his commute such that “[a]t the time it happened [he] had to change cars each side of it.” Horace incorporates these photos that record the city’s historic events into letters that detail his own personal life. Using these photo postcards, senders recorded and shared important events relevant to and connected with their own lives.

- Rosetti Studios. (1909). Result of heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09 (UL_1624_03_0335) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361442

So, does this answer why disasters and accidents were a relatively common depiction in photo postcards? Yes—photo postcards were a key type of personal correspondence. They were used not only to display pictures appealing to tourists and potential settlers, but to communicate about major events relevant to their senders’ lives. Created at the height of the early 20th-century photo postcard craze, they were likely part of ongoing conversations between parties. A single postcard may be a supplement to letters, other postcards, or even phone calls. This means that a postcard of a burnt-down Fernie, B.C. wouldn’t be out of the blue, but instead elaborating on previous conversations. These postcards were one aspect of a larger correspondence that encompassed different aspects of the senders’ lives. Senders could use these postcards to document landmark events in places close to them, as with the [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.]; as well as to weave historical events into records of their own lives, whether those events were some scheduled celebration, or an unexpected accident or disaster.

References

Armitage, S. J. (1908). Fernie, B.C., After the Fire of Aug. 1st. 1908 (UL_1639_0003) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371490

Barrowclough, G. A. (1910). A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. Car, Vancouver, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0040) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361427

Joseph Frederick Spalding—Photographer – Tourist – Visionary : Summary. (2006). University of Victoria Cultural Property Community Research Collaborative. https://maltwood.uvic.ca/cura/projects/joseph_spalding/home.html

Leung, B. (2020, December 18). Exploring Barrowclough’s Postcards. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections. https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/2020/12/18/the-postcards-of-george-alfred-barrowclough/

Photo Postcards. (n.d.). University of Calgary Archives and Special Collections. https://asc.ucalgary.ca/photohistory/photo-postcards/

Rosetti Studios. (1909). Result of heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09 (UL_1624_03_0335) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361442

Rosetti Studios—Stanley Park Collection. (n.d.). University of British Columbia Library Open Collections. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/rosetti

Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

[unknown]. (1908). Fernie after the fire (UL_1638_0051) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361853

[unknown]. (1914). [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.] (UL_1624_02_0086) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0360930

No CommentsPosted in Collections, Exhibitions, Frontpage Exhibition, Research and learning, Uncategorized | Tagged with

Reading Room Closed

Posted on October 20, 2022 @7:15 am by cshriver

Rare Books and Special Collections and University Archives Reading Room closed through January 31, 2023

The Rare Books and Special Collections and University Archives reading room will be temporarily closed from August 1, 2022 through January 31, 2023 for upgrades.

To accommodate these upgrades, there will be some changes to library services. RBSC and UA will provide some reproduction services and digital instructional support during this time. Some collections maybe be inaccessible until 2023.

Please contact Rare Book and Special Collections or University Archives for more information on supports available for remote research and instructional support requests. You can also contact specific members of the RBSC team.

Thank you so much for your patience and support during these necessary upgrades!

No CommentsPosted in Announcements, News, Services | Tagged with

![[Chinese wedding portrait].](https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/files/2023/02/Chinese-Wedding1.0218434-768x577.jpg)

![[Wedding portrait of Yip Him and Lee Lawn Fan].](https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/files/2023/02/Yip-Wedding1.0355132-768x1176.jpg)