A valentine from RBSC

Posted on February 8, 2023 @4:24 pm by cshriver

In honour of Valentine’s Day, a poetic interlude from one of RBSC’s archivists, Krisztina Laszlo.

Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

We have some romantic archives for you!

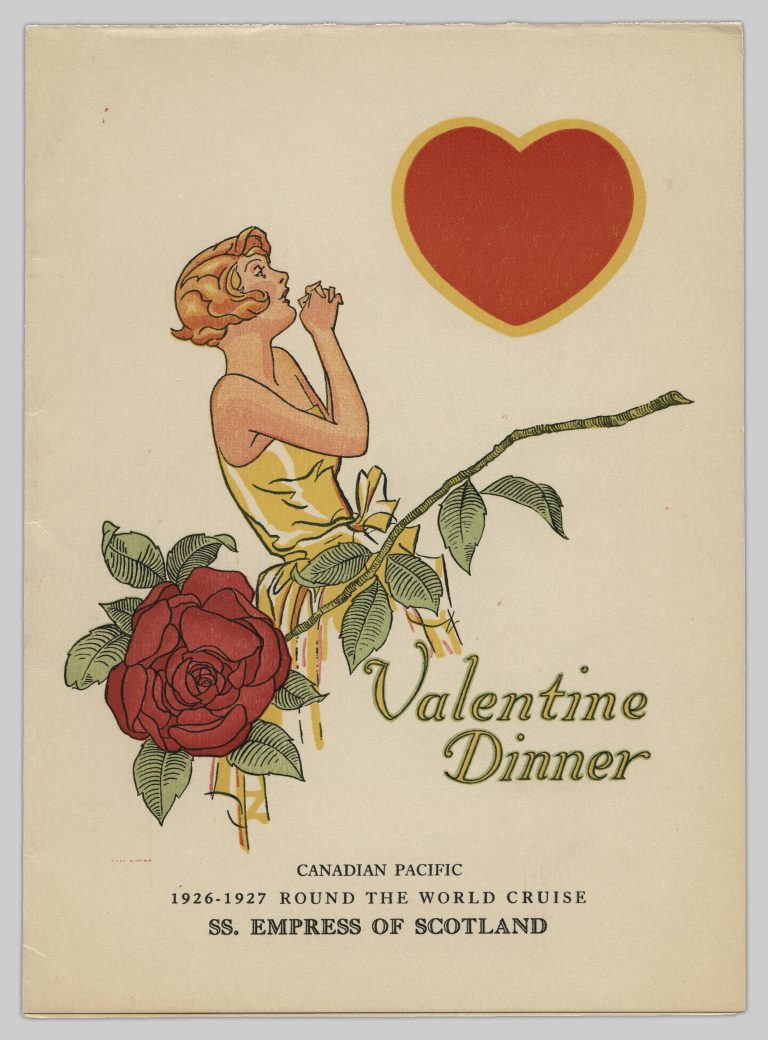

To celebrate St. Valentine’s Day this year, please enjoy a few selections from our collections.

- [Chinese wedding portrait]. The Chung Collection. CC-PH-00331

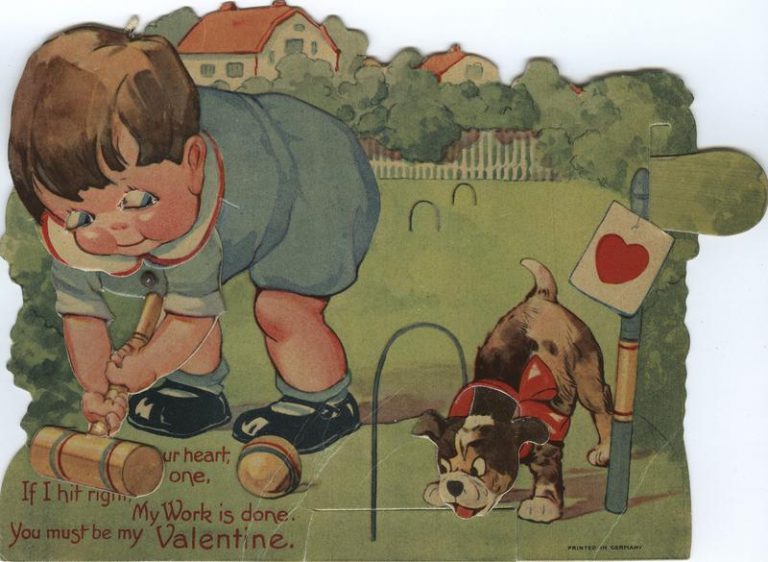

- Valentine, c.1919. Tremaine Arkley Croquet Collection. Croquet-Box6-0015

- Mr. and Mrs. Kantaro Kadota, 60th wedding anniversary, Vancouver, B.C. Japanese Canadian Photograph Collection. JCPC-25-125

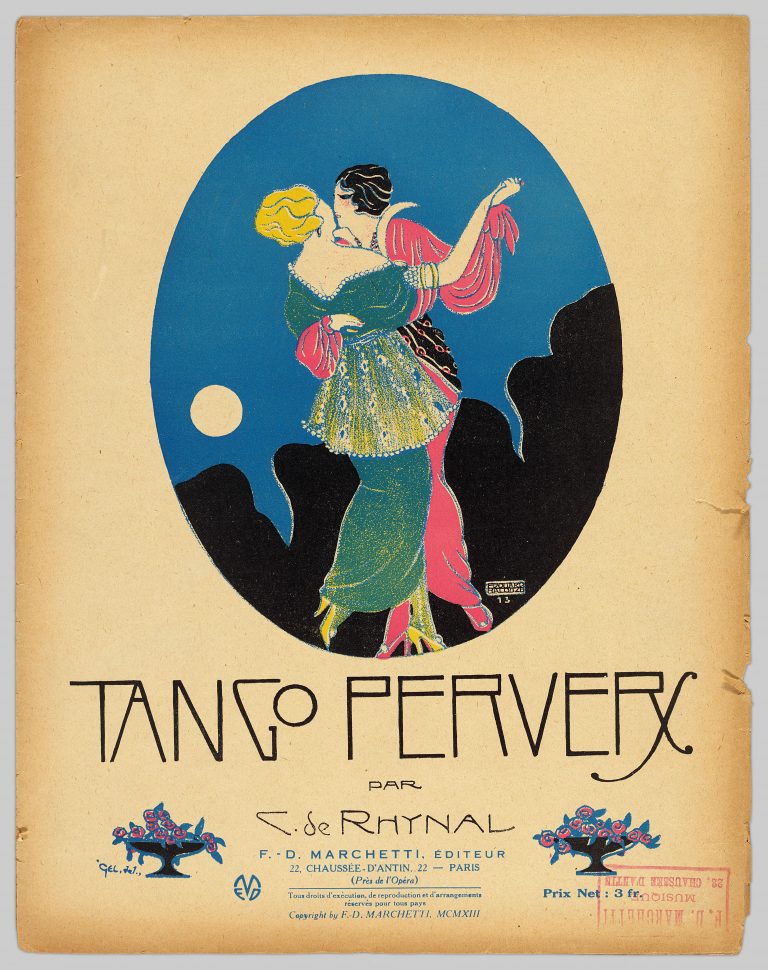

- Tango pervers. spam941B

- [Wedding portrait of Yip Him and Lee Lawn Fan]. The Chung Collection. CC-PH-10676

- Menu from the Valentine dinner on the Empress of Scotland’s 1926-1927 world cruise. The Chung Collection. CC-TX-246-5-12

“They also serve:” Honouring Alexis Alvey

Posted on November 1, 2022 @9:38 am by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger James Goldie for contributing the below post! James was formerly a student archivist with Rare Books and Special Collections and is now Records and Privacy Analyst with Douglas College. This encore blog post was first published in 2019.

“They also serve:” A. Alexis Alvey and the navy’s first female service members

Unit Officer A. Alexis Alvey of the W.R.C.N.S.

Her mother calls her “the Canadian lieutenant” and the girls in the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service call her “Chiefie”…

So begins a 1943 Royal Canadian Navy press release announcing the promotion of Lieutenant Amelia Alexis Alvey to Unit Officer at H.M.C.S. Stadacona, a rank equivalent to that of an army captain. This new position – granted just a year after she first enlisted – meant Alvey was in charge of more than 1,100 Halifax-based service members from the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS), known as Wrens. More than a third of all Wrens were stationed at H.M.C.S. Stadacona in Halifax.

Alvey (who went by A. Alexis Alvey) was born November 22, 1903 in Seattle, Washington. After completing her undergraduate studies in New York, Alvey studied science at McMaster University (1932-1933) and went on to work as chief photographic technician at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine. It was during this period she gained Canadian citizenship. After the outbreak of World War II, Alvey helped organize the businesswomen’s company of the Toronto Red Cross Transport Corps and commanded it for two years. She had also served as lecturer to the entire Transport Corps for Military Law, Map Reading, and Military and Naval Insignia.

Recruitment advertisements ran in magazines throughout Canada from 1942-1944, reminding readers that women could now serve in the navy as part of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service.

Men Can’t Do It Alone

In 1942, top brass in the Canadian navy realized they could not solely rely on men in their fight against Hitler’s forces. They contacted the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) in London requesting assistance in the formation of a Canadian counterpart. “Please send us a Mother Wren,” they said, according to Alvey. Those “mother wrens” were Joan Carpenter and Dorothy Isherwood, who came to Canada and established the WRCNS later that year. Alvey was among the first to enlist.

Until then, the Canadian navy had been an all-male service. As one member wrote in 1943: until the establishment of the WRCNS, “ships and shore establishments alike were manned by men, and knitting seamen’s stockings, or collecting magazines, games and special parcels for ships’ crews at sea was about the limit of any contribution made by women.”

Women were not permitted to serve in combat roles, however, they took over the navy’s on-land operations, which freed up male service members to join battles at sea. The Wrens worked as signallers, wireless-telegraphers, writers, information and intelligence workers, postal clerks, research assistants, cooks, stewards, wardroom attendants, laundry assistants, and more.

Rising Through The Ranks

A. Alexis Alvey (far right) with fellow “Wrens” at the W.R.C.N.S. training centre in Galt, Ontario.

In her first year with the WRCNS Alvey was appointed acting Chief Petty Officer Master-at-Arms. Her other assignments included duty as Deputy Unit Officer H.M.C.S. Bytown (Ottawa), duty with the Commanding Officer Pacific Coast H.M.C.S. Burrard (Vancouver), assignment as Unit Officer, Lieutenant H.M.C.S. Bytown, and finally Unit Officer to H.M.C.S. Stadacona (Halifax). She was responsible for training and running practice drills, developing policies, and meeting with officers from ships that arrived in Halifax.

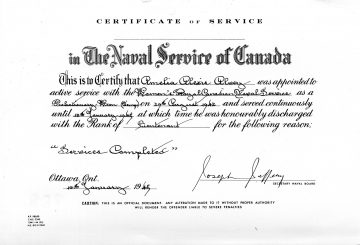

She served with the WRCNS from August 1942 to January 1945.

The A. Alexis Alvey Fonds

After the war, Alvey returned to her home city of Seattle where she worked as a librarian at the University of Washington. However, she never forgot her time with the WRCNS. For the rest of her life, Alvey organized and attended Wrens reunions, she wrote articles and histories about the service, and collected all manner of documents, memorabilia, and ephemera related to the “The Women’s Navy” as it was sometimes called.

The Royal Canadian Navy’s certificates of service were designed with only male service members in mind.

These records along with Alvey’s personal papers and an extensive collection of photographs are housed at UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections and are available for research.

The materials that make up the A. Alexis Alvey fonds express the profound sense of pride shared by Alvey and her fellow Wrens with respect to their years of military service. An essay commemorating the WRCNS silver anniversary by Isabelle NcNair (née Archer) captures this pride. In it, a grandmother tells her granddaughter the story of the Wrens. “But Grannie, I thought Grandad won the war,” asks the child. “No dear,” responds her elder, “I did.”

No CommentsWish You Were Here?

Posted on August 17, 2022 @4:05 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Gabriella Cigarroa for contributing the below post! Gabriella is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and completed a professional experience with RBSC this summer.

From the Langmann Collection: Early 20th-Century Postcards Depicting Disasters and Accidents

This summer, I completed a Professional Experience at RBSC to assist with cataloguing unprocessed materials. I wanted to work with RBSC to learn more about how special collections document the community they serve. At first, I catalogued posters, broadsides, prints, and other kinds of items that documented B.C. history. A few weeks in, I was offered another project: writing about the Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. I worked specifically with the digital collection, a subset of the larger collection of more than 18,000 photographs that documents B.C. from the 1850s to 1970s.

In the Langmann collection, I encountered many postcards whose picture sides captured disasters and accidents. Postcards today generally feature scenes more appealing to tourists, often picturesque landscapes or buildings. While postcards of this type are present in the Langmann collection, there are also plenty with more unexpected subjects—including that of disasters and accidents. Why was this subject matter chosen as a relatively common subject of photography for postcards, to be sent as correspondence? And what about the format of a postcard is different today from a hundred years ago such that these postcards’ imagery surprised me?

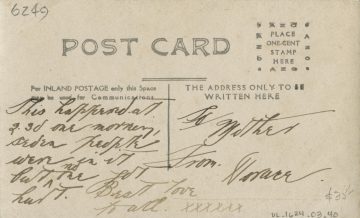

Two postcards first caught my eye, illustrating the contrast between friendly personal correspondence and an image of a disaster or accident. The first, titled A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. car, Vancouver, B.C., features a photograph of a streetcar crash’s aftermath. The photographer is positioned inside the wrecked building, framing the streetcar with the storefront’s windows. Inside the building, debris is piled haphazardly on the windowsill. A group of children smiles, looking in the window of the presumed storefront, maybe even noticing the photographer inside. On the postcard’s back, the sender, Horace, writes to his mother: “This happened at 2.30 one morning, seven people were in it but no one got hurt. Best love to all.” I questioned, why did Horace send this photo and information to his mother?

- Barrowclough, G. A. (1910). A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. car, Vancouver, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0040) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361427

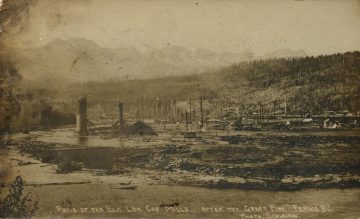

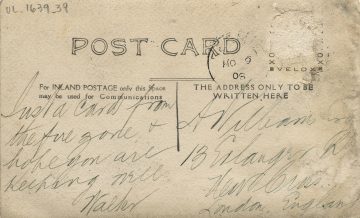

The other postcard presents a picture taken after a fire in Fernie, B.C. In the photographed landscape, few buildings remain intact. Some smokestacks rise from the rubble, while burnt-out husks of trees stretch into the distance. I was struck by the casual language on the postcard’s back, as a man named Walter writes to someone in England: “Just a card from the fire zone + hope you are keeping well.”

- Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

I took a step back to consider the context of these postcards’ creation. As briefly discussed earlier, the purpose of a postcard today is different from that of the other materials I catalogued this summer. The materials outside of the Langmann collection—posters, prints, broadsides, and so forth—were generally created with a broad audience in mind. Postcards, however, are often for personal correspondence. Today, this difference in audience would typically mean a major difference in subject matter. Usually, a person today would want to show a loved one picturesque landscapes, not tragic news relevant primarily to their neighbouring residents. Was this different a hundred years ago?

- Armitage, S. J. (1908). Fernie, B.C., After the Fire of Aug. 1st. 1908 (UL_1639_0003) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371490

- Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

The postcards I selected are roughly from between 1905-1915. It turns out that this period was in the midst of a postcard craze, in which an estimated one billion postcards were created each year in North America (Photo Postcards, n.d.). About ten percent of these postcards were real-photo postcards—silver-gelatin photographs made either as one-offs or in small numbers. In 1903, Kodak had created the A3 camera and an accompanying photograph development kit that allowed anyone to produce a silver-gelatin photograph on postcard paper (Photo Postcards, n.d.). This technological development that allowed increasingly portable and cheap photography, alongside an inexpensive postal system, encouraged layperson photographers to ply their trade. This real-photo postcard craze lasted from 1905 to 1930, although the process was still used into the 1950s (Photo Postcards, n.d.), permitting anyone with such a camera to make a postcard.

Most photo postcards in the Langmann collection are taken by photographic printing companies or unknown photographers. However, the photo postcards I found depicting disasters and accidents were mostly created by individual photographers or unknown individuals. Since anyone with a postcard camera could take postcard photos, the postcards without credit on them could be by anyone, including their senders. Alongside individuals taking their own photos, the postcard camera allowed for a rise in amateur photographers and photography studios.

The photo postcards in the Langmann collection featuring disasters and accidents seem to be created by a few identifiable photographers: Joseph Frederick Spalding, Rosetti Studios, and George Alfred Barrowclough. All three photographed more than the disasters and accidents I initially encountered. Joseph F. Spalding is known for documenting the history of Fernie, B.C., especially the reconstruction after the fire in 1908 (Joseph Frederick Spalding, 2006). Rosetti Studios was run by Lionel Haweis, who is best known for his series of photographs recording the development of Stanley Park (Rosetti Studios – Stanley Park Collection, n.d.). Lastly, Barrowclough is now seen as more of a photojournalist (for a more in-depth discussion of Barrowclough’s work, see my colleague Brandon Leung’s blog post). These photographers chose what they thought should be documented history, and even reproduced as postcards. Whether amateur photographers, commercial studios, or people who happened to own a postcard camera, they all captured what they likely considered significant contemporary events.

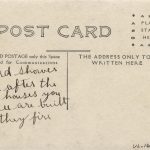

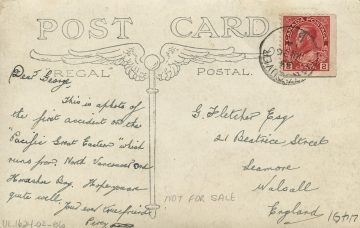

With some postcards, the disasters and accidents were likely considered one type of an event to record, and even to share with loved ones as news. For example, the postcard of the Fernie fire zone discussed earlier is one in a series documenting the town’s recovery and reconstruction (Joseph Frederick Spalding, 2006). Someone sending such postcards as correspondence could discuss the progress of Fernie’s recovery. In the case of other postcards, context concerning the senders’ intentions can be derived from reading the postcards’ letter component. We can look at [View of the Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.]. In the photograph, a train car lies on its side next to train tracks. A couple of people view the train car while others walk by. The back reads: “This is a photo of the first accident on the ‘Pacific Great Eastern’ which runs from North Vancouver and Horseshoe Bay.” The sender provides the context of the Pacific Great Eastern and describes its historical import as the railway’s first accident, marking it as a notable event.

- [unknown]. (1914). [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.] (UL_1624_02_0086) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0360930

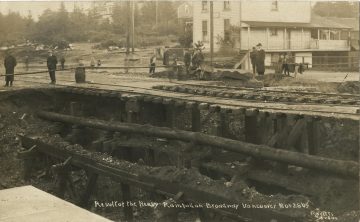

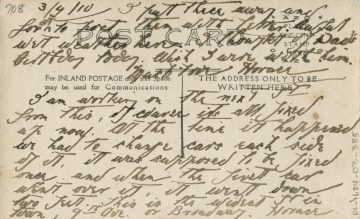

However, this kind of proto-, personal photojournalism is not the only reason for sending these types of postcards. Some postcards seem to be parts of bigger conversations held outside of a single letter. The postcard featuring the fire zone at Fernie is one example, as the recipient would be able to identify the unnamed “fire zone” mentioned in the letter without context from outside the single postcard. Another is the Result of the Heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09. The photograph displays a street in the aftermath of the rainfall, with a large pit and metal structures where the street should be. A set of tracks still runs over the pit. A few people on the side of the pit opposite the photographer look on. On the back of the postcard, a man named Horace writes, “This is next to where I’m working.” He describes not only the event of the crash, but how it interacts with other aspects of the city like the “awful wet weather,” as well as how the event affected his commute such that “[a]t the time it happened [he] had to change cars each side of it.” Horace incorporates these photos that record the city’s historic events into letters that detail his own personal life. Using these photo postcards, senders recorded and shared important events relevant to and connected with their own lives.

- Rosetti Studios. (1909). Result of heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09 (UL_1624_03_0335) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361442

So, does this answer why disasters and accidents were a relatively common depiction in photo postcards? Yes—photo postcards were a key type of personal correspondence. They were used not only to display pictures appealing to tourists and potential settlers, but to communicate about major events relevant to their senders’ lives. Created at the height of the early 20th-century photo postcard craze, they were likely part of ongoing conversations between parties. A single postcard may be a supplement to letters, other postcards, or even phone calls. This means that a postcard of a burnt-down Fernie, B.C. wouldn’t be out of the blue, but instead elaborating on previous conversations. These postcards were one aspect of a larger correspondence that encompassed different aspects of the senders’ lives. Senders could use these postcards to document landmark events in places close to them, as with the [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.]; as well as to weave historical events into records of their own lives, whether those events were some scheduled celebration, or an unexpected accident or disaster.

References

Armitage, S. J. (1908). Fernie, B.C., After the Fire of Aug. 1st. 1908 (UL_1639_0003) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371490

Barrowclough, G. A. (1910). A bad smash between a drug store window and a st. Car, Vancouver, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0040) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361427

Joseph Frederick Spalding—Photographer – Tourist – Visionary : Summary. (2006). University of Victoria Cultural Property Community Research Collaborative. https://maltwood.uvic.ca/cura/projects/joseph_spalding/home.html

Leung, B. (2020, December 18). Exploring Barrowclough’s Postcards. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections. https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/2020/12/18/the-postcards-of-george-alfred-barrowclough/

Photo Postcards. (n.d.). University of Calgary Archives and Special Collections. https://asc.ucalgary.ca/photohistory/photo-postcards/

Rosetti Studios. (1909). Result of heavy rainfall on Broadway, Vancouver, Nov. 28, ’09 (UL_1624_03_0335) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361442

Rosetti Studios—Stanley Park Collection. (n.d.). University of British Columbia Library Open Collections. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/rosetti

Spalding, J. F. (1908). Ruins of the Elm Lb Cos Mills, after the great fire, Fernie, B.C. (UL_1639_0039) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0371568

[unknown]. (1908). Fernie after the fire (UL_1638_0051) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0361853

[unknown]. (1914). [View of Pacific Great Eastern railway accident, Vancouver, B.C.] (UL_1624_02_0086) [Gelatin silver print]. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0360930

No CommentsI Know We’ll Meet Again

Posted on June 20, 2022 @1:33 pm by cshriver

As we acknowledge the 80th anniversary of the forced dispersal, internment, and dispossession of Japanese Canadians from the coastal regions of British Columbia, we’re pleased to be able to share an online exhibition curated by Mya Ballin and Sasha Gaylie, both graduate students at UBC’s School of Information.

Many thanks to Mya for sharing her thoughts about the process of curating the exhibition. Mya and Sasha’s work on I Know We’ll Meet Again: Correspondence and the forced dispersal of Japanese Canadians was done as part of a summer 2021 professional experience project with RBSC and the Asian Library at UBC.

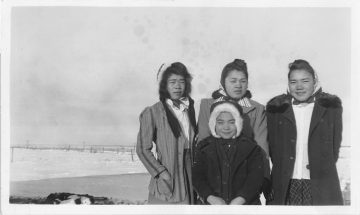

University of British Columbia Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Joan Gillis fonds. RBSC-ARC-1786-PH-02. Teruko Mototsune, Kanako Mototsune, Haruye Mototsune, and Sumi Mototsune. Raymond, Alberta – February 8th, 1943.

This project was a labour of much care over a very brief period of time. Completed in two months, my project partner, Sasha, and I found ourselves very quickly immersed in the written selves that are contained within the letters in the Joan Gillis fonds, deeply emotionally drawn to the details that the writers felt were safe to share with Joan. When reading the letters, it’s hard not to feel like these are your old school friends, too.

We wanted to create an exhibit that not only helped to contextualize the letters and the period in which they were being written, but also to allow the letter writers’ voices to stand on their own so that folks visiting the exhibit might have a similarly emotional encounter with these young individuals through their words alone.

To this end, the exhibit has two parts:

The first part of the exhibit is a more traditional curation of the letters. We offer you the opportunity to view the collection through our eyes, providing interpretation and information that focuses on some of the key themes that emerged from our reading and experience of the letters.

The second part of the exhibit is an opportunity to explore the transcripts of some of the letters. While we have offered the ability for a guided tour through them using a subject visualization tool, it is also possible to view each transcript one by one without our analysis appearing on the screen.

We hope that presenting the materials in this manner offers different ways of engaging with the material and different opportunities to ‘meet’ its authors.

About the exhibition

I Know We’ll Meet Again: Correspondence and the forced dispersal of Japanese Canadians, focuses on a selection of letters from the Joan Gillis fonds written by young Japanese Canadians who were among the approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians from British Columbia who were forcibly dispersed from their homes as a result of the Canadian Federal Government’s Orders in Council. The exhibition details their deep homesickness and sense of isolation from their friends and communities, the new living and labour conditions they had to endure, their continued sense of Canadian identity even as the government labeled them “alien,” the bright spots they were able to find in their present conditions, and their imaginations for the future.

No CommentsA new way to picture Canada

Posted on March 9, 2022 @3:09 pm by cshriver

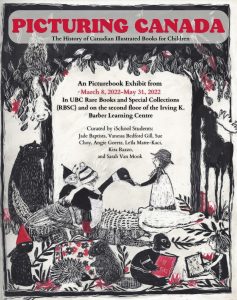

Rare Books and Special Collections at UBC Library is delighted to announce a new exhibition: Picturing Canada: The History of Canadian Illustrated Books for Children.

Rare Books and Special Collections at UBC Library is delighted to announce a new exhibition: Picturing Canada: The History of Canadian Illustrated Books for Children.

Many thanks to guest bloggers Jade Baptista, Vanessa Bedford Gill, Sue Choy, Angie Goertz, Leïla Matt-Kacai, Kira Razzo, and Sarah Van Mook for contributing the below post! This intrepid team of graduate students at the UBC School of Information or in the Master of Arts in Children’s Literature Program curated this picturesque new exhibition under the supervision of Dr. Kathryn Shoemaker, Adjunct Professor with the UBC School of Information.

Picturing Canada is an exhibition that will take visitors on a journey from the earliest published Canadian illustrated children’s books to current ones. Commencing with Northern Regions, published in 1825 to On the Trapline, a 2021 award winning picturebook, nearly 200 years of children’s books in Canada are covered. This exhibition explores the changing historical and cultural aspects of Canadian identity through the lens of children’s illustrated books. This exhibition is a testament to the artists, authors, publishers and ultimately readers, who shaped and continue to shape, children’s literary culture in Canada. The Picturing Canada exhibition can be thought of as a tapestry of over 120 Canadian children’s books, with each thread made up of our curated individual book selections. We could not hope to include every book and many threads were left out of the display, mostly due to space constraints. However, we encourage the visitor to celebrate the books we have chosen and ponder how they might picture Canada at different points in history.

Picturing Canada: The History of Canadian Illustrated Books for Children is on display on level 1 (RBSC reading room) and level 2 (main foyer) of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre from March 8 through May 31, 2022. The exhibition is free and open to the public, and people of all ages are encouraged to attend. A complete catalogue of the exhibition can be downloaded here. For more information, please contact Rare Books and Special Collections at (604) 822-2521 or rare.books@ubc.ca. You can also visit an exhibition site created by the curators.

“For All Time” satellite display

Posted on January 12, 2022 @10:35 am by cshriver

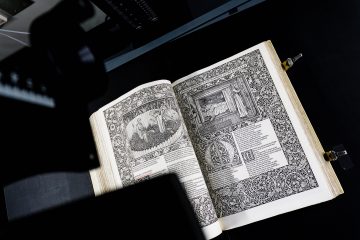

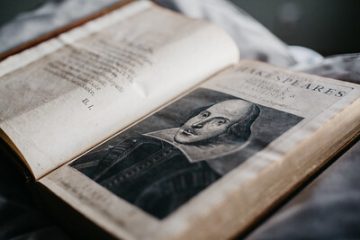

UBC and Rare Books and Special Collections at UBC Library is thrilled to announce the acquisition of a complete first edition of William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. Published in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, the First Folio includes 36 of Shakespeare’s 38 known plays. The texts, edited by Shakespeare’s close friends, fellow writers and actors, are considered the most authoritative of all early printings.

UBC and Rare Books and Special Collections at UBC Library is thrilled to announce the acquisition of a complete first edition of William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. Published in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, the First Folio includes 36 of Shakespeare’s 38 known plays. The texts, edited by Shakespeare’s close friends, fellow writers and actors, are considered the most authoritative of all early printings.

In partnership with the Vancouver Art Gallery, the newly acquired First Folio will be exhibited to the public from January 12 to March 22 along with three subsequent seventeenth-century Folio editions of Shakespeare’s plays. The exhibition, For All Time – The Shakespeare FIRST FOLIO marks the first time that all four Folios have been presented in Vancouver. The exhibition will be accompanied by an audio mobile guide featuring the voice of Christopher Gaze, Founding Artistic Director, Bard on the Beach Shakespeare Festival, in addition to a series of public programs, including talks, performances and more. For further information, please visit vanartgallery.bc.ca.

To compliment the exhibition at the VAG, a display of books from RBSC’s collection that support early modern and Shakespeare studies will be up through the end of February 2022 in the Rare Books and Special collections reading room. The display includes works by Shakespeare’s contemporaries, such as Ben Jonson, Francis Beaumont, and John Fletcher, materials that help contextualize Shakespeare’s world, and materials that demonstrate Vancouver and British Columbia’s on-going fascination with the Bard.

The display, which is free and open to the public, is available to visit in the RBSC reading room, Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. For more information, please contact Rare Books and Special Collections at (604) 822-2521 or rare.books@ubc.ca

No CommentsChung Collection exhibition closure

Posted on October 8, 2021 @11:27 am by cshriver

The Chung Collection exhibition room will be temporarily closed for two weeks from Monday, October 18 through Friday, October 29 for conservation work. Our apologies for the inconvenience. The Chung Collection exhibition room will be open as usual on Monday, November 1. Thank you for your patience!

The Chung Collection exhibition room will be temporarily closed for two weeks from Monday, October 18 through Friday, October 29 for conservation work. Our apologies for the inconvenience. The Chung Collection exhibition room will be open as usual on Monday, November 1. Thank you for your patience!

Science Literacy Week 2021

Posted on September 17, 2021 @4:27 pm by cshriver

In honour of Science Literacy Week 2021’s theme of climate, our wonderful Forestry and Natural Resources Archivist, Claire Williams, has highlighted some of Rare Books and Special Collections’ many fonds related to British Columbia’s environment in the UBC Library Guide to Science Literacy Week.

In honour of Science Literacy Week 2021’s theme of climate, our wonderful Forestry and Natural Resources Archivist, Claire Williams, has highlighted some of Rare Books and Special Collections’ many fonds related to British Columbia’s environment in the UBC Library Guide to Science Literacy Week.

These fonds include records documenting historical climate data, struggles for climate action, and the development of creative works to educate others on the importance of climate issues. You can read a general description of the fonds below, or can click through to the full inventories for more details.

Angus Elias fonds

E. A. Royce fonds

The fonds consists of a diary of Royce’s activities at Christina Lake (1934-1943), including some financial accounts and weather reports for the winters of 1935/36 and 1936/37. The diary also lists the names of many families in the area.

Greenpeace International, Stitching Greenpeace Council fonds

Jim Hann documentary video collection

Joan Sawicki fonds

If you would like to consult any of these materials in person, you can visit Rare Books and Special Collections. To learn about other archival holdings related to natural resource extraction and the climate, check out RBSC’s Forest History and Archives Research Guide.

Science Literary Week runs from September 20 to 26, 2021. For more details about Science Literacy Week activities at the Library, including other resources and several events you can attend, explore the UBC Library Guide to Science Literacy Week.

No CommentsInternational Kelmscott Press Day

Posted on June 25, 2021 @2:51 pm by cshriver

As we celebrate International Kelmscott Press Day, we hope you enjoy this special lecture by Dr. Gregory Mackie, Associate Professor in the Department of English, and UBC Library’s Norman Colbeck Curator, titled “A Nameless City in a Distant Sea”: William Morris, Arts and Crafts, and the Kelmscott Chaucer in British Columbia.

No Comments

Celebrating UBC’s Kelmscott Chaucer on International Kelmscott Press Day

Posted on June 25, 2021 @1:24 pm by cshriver

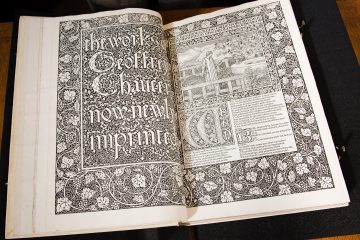

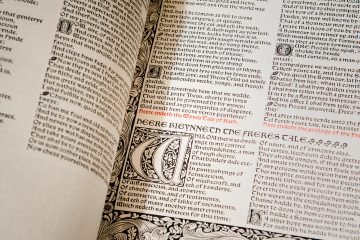

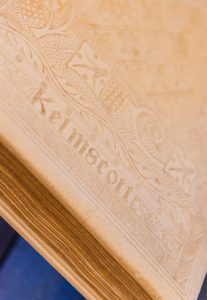

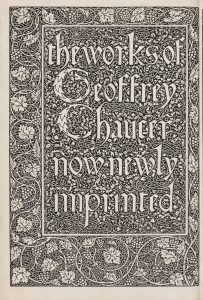

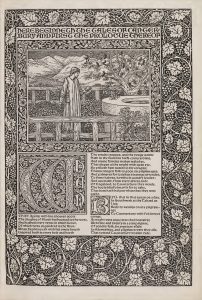

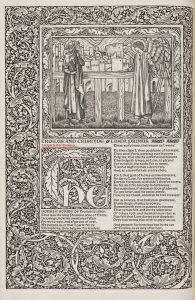

In honour of International Kelmscott Press Day on June 26, 2021, we’re celebrating and reflecting on the acquisition of the UBC Library’s own Kelmscott Chaucer.

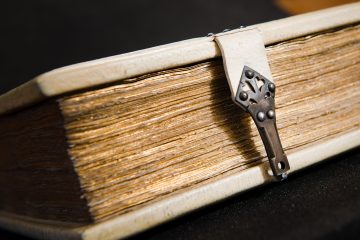

The poet William Butler Yeats described it as the “most beautiful of all printed books.” Artist and illustrator Edward Burne-Jones likened it to a “pocket cathedral.” At UBC Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections, we know it as the single most requested book in our collection.

William Morris’s printed masterpiece, the complete works of Geoffrey Chaucer published by Morris’s Kelmscott Press, known as the Kelmscott Chaucer, is a book of renown on par with the likes of Shakespeare’s folios. It is part of the “triple crown” of fine press printing referred to by book historians and collectors, made up of three remarkable works held to represent the pinnacle of the book arts of the modern fine press movement. Issued in a limited edition of only 438 copies in 1896, the Kelmscott Chaucer is tracked and studied to such a degree that there is a scholarly census of each copy’s history and current custodian, which is kept up-to-date on the author’s website.

A joint acquisition by UBC Library and the faculty of arts, the Kelmscott Chaucer was purchased in the summer of 2016 after two years of fundraising efforts, which included a substantial donation from the B.H. Breslauer Foundation of New York. UBC faculty, community members and UBC’s Centennial Initiatives Fund also contributed. The drive to acquire the book was based not only on its significance to book history and fine press printing generally, but to honour and celebrate the 50th anniversary of the donation to UBC Library of the world-renowned Colbeck Collection of 19th-century literature, which includes several extremely rare Kelmscott Press books. RBSC’s copy of the Kelmscott Chaucer, known as the “Slater-Gribbel-Schimmel” copy, boasts not only the Morris-designed white pigskin binding, executed by the Doves Bindery (one of only 48 copies in the world with this particular binding), but also a rare printer’s proof with variant typesetting for the opening page.

While we at RBSC were beyond thrilled with the acquisition after many years of effort, we had no idea that the public response to the Kelmscott Chaucer would be so enthusiastic! We were amazed that the Vancouver Sun chose to feature the acquisition on the front page, and promptly ran across campus trying to buy commemorative copies of the paper in our excitement. And as soon as the word got out, visitors started arriving to experience the book in person. People from all over British Columbia and beyond made the trek out to UBC’s somewhat isolated campus, individually and occasionally in groups organized especially for the occasion, to feel the Batchelor handmade paper, hear the satisfying “swish” of the pages as they turn, to marvel at the intricacy and detail of Burne-Jones’s illustrations and Morris’s decorations, to admire the stunning binding, and to enjoy the feeling of connection to history. In the first three years after our Kelmscott Chaucer came to RBSC, it was circulated to visitors in our reading room and classes an average of twice a week and outstripped our Second Folio of Shakespeare and our 15th century book of hours in popularity.

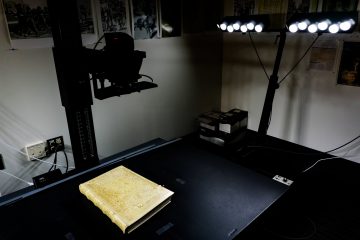

But since one can’t expect every fan of William Morris or arts and crafts printing to make the trip to UBC, our colleagues at UBC’s Digitization Centre scanned the entire work in 2018, making it freely and publically accessible through the Library’s Open Collections, where it has been viewed nearly 3000 times. The Library Communications team was even inspired to create a downloadable colouring book featuring pages from the Kelmscott Chaucer, helping to share the beauty of the book more widely.

We feel so lucky to be able to not only act as stewards and custodians for this exemplar of book design and printing history, but to ensure that it is accessible to the UBC community, the people of British Columbia, and lovers of beauty the world over, to be experienced, celebrated, and enjoyed. Happy International Kelmscott Press Day!

No Comments![[Chinese wedding portrait].](https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/files/2023/02/Chinese-Wedding1.0218434-768x577.jpg)

![[Wedding portrait of Yip Him and Lee Lawn Fan].](https://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/files/2023/02/Yip-Wedding1.0355132-768x1176.jpg)