Archival work in a global pandemic

Posted on May 31, 2021 @1:29 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Sadaf Ahmadbeigi for contributing the below post! Sadaf has just completed course work as a graduate student at UBC’s School of Information and has been working as an intern with Rare Books and Special Collections.

Managing Archival Projects During a Global Pandemic

A conversation with Krisztina Laszlo

As I am writing this blog it has been more than a year since the Rare Books and Special Collection’s reading room has been closed to visitors and most of the staff due to Covid-19 pandemic. For this blog I reached out to Krisztina Laszlo, senior archivist at RBSC, to see how this year and a half has affected the way she’s been carrying out her work. Below are highlights of the conversation we had over Zoom.

As I am writing this blog it has been more than a year since the Rare Books and Special Collection’s reading room has been closed to visitors and most of the staff due to Covid-19 pandemic. For this blog I reached out to Krisztina Laszlo, senior archivist at RBSC, to see how this year and a half has affected the way she’s been carrying out her work. Below are highlights of the conversation we had over Zoom.

Sadaf Ahmadbeigi: How did your job change after you were told that all work has to be moved into remote work?

Krisztina Laszlo: When we moved into remote work last March, we had three students and two interns, including you. So, one of the key priorities at that time was finding meaningful work for our students and student interns. We had to figure out what projects they could do from a remote environment because students in house mainly do arrangement and description work, and working on reference questions, neither of which was possible at that time due to COVID.

SA: How long did it take for you to plan the new projects for the students?

KL: Not very long. We first had to deal with our immediate students. There were some projects that I’ve always wanted to have done but there’s always so much pressure to get arrangement and description done that it seemed like we never had time for them. These were tasks like converting our old PDF finding aids into AtoM, writing blog posts as a way to create content and working on LibGuides. We were looking for the types of meaningful work for students that would meet the needs of the institution and help create better experiences for patrons. For example, creating outreach components in the form of blog posts would allow meaningful experience for students and is also useful for the researcher and patron side of things. So, we asked the students and interns to switch to doing these tasks.

The other thing that changed as the result of COVID was the nature of our work with donors. There was a lot of donor interaction in terms of what had already been donated because we had to delay getting their tax receipts. I needed to communicate the process of issuing tax receipts to the doners so they could understand the reason for this delay. Before issuing tax receipts, we need to process the material, which is usually done by students who no longer had access to them. Then we have to get a monetary appraisal done which requires bringing the person into the facility to do the appraisal. And then we can issue the tax receipt. And now due to COVID, we had to stop that whole process. So, it was very important to communicate all this with the doners.

SA: Other than the tax receipts, the rest of your work with the doners has stayed the same as before, right?

KL: Yes. [For new donations], under normal circumstances, I would go to a donor’s house to do a site visit if they were in the city. And sometimes I travel, if we think the records are going to be valuable. I have traveled around BC to look at records before. Sometimes I’ll advise on site whether we can accept the material, or a part of it or none of it at all. When it comes to UBC whoever’s doing the processing will go through it more carefully. Now that it’s no longer possible to do a site visit, there is a lot of communication over email, phone or zoom to determine what we can accept. With COVID we can only be on site at UBC for limited hours. This means that the transfer of the materials to RBSC has become exponentially more difficult to coordinate. Couriers who are usually in charge of dropping off the materials are notoriously hard to coordinate with. They often give you a window, between 7am and 8pm, and we can’t schedule an exact time with them. There are other logistical issues as well. So, there’s all sorts of things that were really easy to do under normal circumstances but are now challenging.

I also found that with COVID more people are spending time at home, so they have time to go through their own personal archives. So, there’s a huge flood of doners that have been contacting us saying that they’ve had time to go through their stuff and ask if we are interested in what they have. I’ve got a huge file, about six inches thick, of just my paper notes of potential donation. This is not even counting all of the emails we received from donors. Now that it’s been over a year since the pandemic, managing all of the communication with doners about the materials that we want to take in is challenging. I keep getting emails from people asking if we are open and if they can bring in their stuff. And I have to say, no, no, not yet. So, the first year to a year and a half once we’re back to normal, it’s just going to be dealing with this backlog, just the backlog that accumulated in the last year and a half, not even touching the backlog that already existed before the pandemic.

SA: Oh wow! What are some new possible records that we might get after the restrictions?

KL: One of the interesting contacts I’ve made during this time is with a retired woman who wrote a book about the history of women at the Vancouver Police Department. I contacted her and we had a great conversation around her process of writing that book and doing research. And I asked her if she has contacts for other women. This is interesting and relevant to RBSC because one of my focuses here is to bring in more records about women’s experiences, and how women have expanded into non-traditional roles is one of the areas of our focus here. Because there wasn’t a lot of careers open to women back then. So, for women to start being police officers in the 60s and 70s points to a really interesting period of feminist history in BC as women started to branch out into this area of work that has been traditionally only for men. I am really excited about these potential records and she’s got connections to other women who might have more archival material.

It’s always important to have enough knowledge about potential donations so that the doners won’t feel like they have to teach us about the importance of what they have. So, for these possible records too I made sure that I have done my research before contacting her. I got a copy of the book and started reading through that to make sure I know enough background so that she can feel comfortable talking about her research process with me. It’s important for doners to be reassured that we have enough knowledge about their records as part of trust building with the donor. A lot of these steps are now done virtually by having phone conversations or in some cases, zoom calls, and lots of email exchanges. Another example of a doner that I work with virtually is an artist who’s really worried about her legacy, and rightly so. She’s been part of an art movement, in the 70s, in which the focus has been predominantly on men. And she was a really integral figure. She has a lot of concerns about when we can take her materials and unfortunately, we can’t take them anytime soon. So, I’ve had a lot of conversations and exchanges with her reassuring her that we do want the records and have sent her a letter of agreement and interest.

These are the interactions and communications that takes up a lot of my time. I’ve also been focusing on grant writing and I seem to have meetings after meetings after meetings. It’s hard to say when my workday starts and when it ends which brings me to the third major challenge that I’ve been facing during the pandemic. With transitioning to working at home I have no balance between work and life. There is a lot of intellectual work involved in what I do and before, I was able to leave work at the end of the day and be done with that. That’s not possible anymore because work is now my kitchen table and I never leave work. The technological challenges of getting my workspace set up also added to it. I mean, these sound like small things but there was a lot of psychological anxiety regarding getting my remote desktop to work properly and having to update our internet and that sort of thing.

SA: It’s so important to talk about this. We usually talk about how the students are dealing with this pandemic, and how hard it is for us. But we don’t really talk about the management and people who are really trying to make our lives easier, and also get the usual work going as if nothing has happened.

KL: It’s funny, there’s been a lot of conversations at the university around productivity, and the belief that people aren’t working as effectively as before. I’ve heard some saying people are only working maybe 60% of their workdays, and they’re just slacking off the rest of the time. And that has absolutely not been my experience, I think I’m producing and working more. And my hours certainly haven’t shifted, if anything they’ve increased because there’s so many projects. One silver lining of this situation is that we’ve really been able to do a lot of work on cleaning up our metadata. One of our staff has been working on an incredible project by adding subject access points to our records on ATOM. We’re doing everything that we needed to do for ages but couldn’t because the pace of life when we’re on site is so hectic that we never have time to actually do these really important projects. Another project that’s amazing and we wouldn’t really have been able to prioritize it before is one that one of our staff who is a native Mandarin speaker is working on. She is adding Chinese language descriptions and name authorities starting with The Chung Collection and eventually moving to our other fonds about Chinese creators. This is so important because then people that don’t have good English skills will be able to search the collections and find material. And again, you’d think that such an important project should have been done before. Why haven’t we done that already? Because we didn’t have time!

SA: No, I hear you. I also know that you’ve done some arrangement and description yourself, right?

KL: Yeah, so that was back when I was going in RBSC, starting in January. I started going in to RBSC to do arrangement and description, one or two days a week and I did that for a couple of months. It was great because I don’t often get to do arrangement and description, that’s always delegated to students or RBSC’s processing archivist. I’m more like the person that spins the plates and does all the juggling. So that was really great to get back to my roots to do arrangement and description. And it was fun also because I think it helped me be a better teacher. I feel like I can help students learn how to do it better by actually going back and doing it myself again. It was a good kind of refresher in my brain. But then again with the increased restrictions I stopped going in about a month ago.

SA: Yeah. And I know sometimes as archivists we worked with difficult record, and then adding to that this pandemic might cause more, I don’t know, compassion fatigue. Do you feel like that happened to you?

KL: If anything, there is more frustration and exhaustion around the constant anxiety and the worry about the state of the world. Anxiety fatigue and constantly having to worry about the state of my health, worrying about the health of my co-workers and my students, which I care about a great deal not just how you guys are doing in terms of the work you do for us, but how the students and my other amazing colleagues at RBSC are doing with coping with all of this. And then there’s making sure that everybody has projects to work on, not just the students, but that the support staff have meaningful work to do and there is of course my own projects. So yeah, there’s that fatigue for sure. We’re really fortunate though, in the sense at RBSC, they’re like my extended family. And we all are very careful about making sure we’re all okay and are checking in with each other. So that has, I think, alleviated a lot of those emotional labor and fatigue challenges, because we’re not fighting against each other to get things done. We’re all in it together. And I acknowledge that, probably, this is not everyone’s experience. But that has really helped with keeping us going.

No CommentsPhil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection

Posted on May 12, 2021 @5:22 pm by cshriver

As recently reported, the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection has been donated to UBC Library Rare Books and Special Collections, along with a generous financial gift. The collection includes over 1800 photographs, hundreds of postcards, as well as textual records, artefacts, and maps of the Klondike Gold Rush era.

RBSC invites its patrons to enjoy the collection through the finding aid, digitally available in our archival database. While the entire collection will be soon be digitized and made available through UBC’s Open Collections, researchers can now explore descriptions for each item in the collection in its archival context through the finding aid.

For users interested in accessing these and other items described in our archival database, please visit the Rare Books and Special Collections Remote Resources and Services Guide.

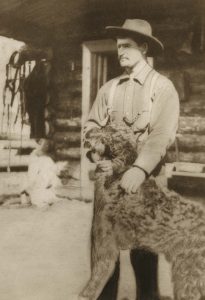

- [John G. Lind in front of cabin with dog]. RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-1250

- 16 and 17 below Hunker– 64. RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-1659

No Comments

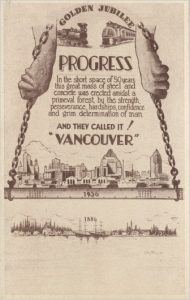

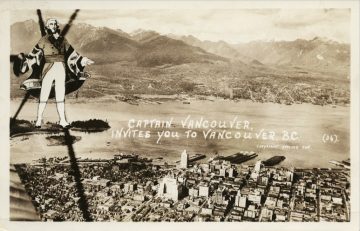

And They Called It Vancouver

Posted on April 7, 2021 @9:14 am by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Ashlynn Prasad for contributing the below post! Ashlynn is a graduate of the UBC School of Information and the curator of the new online exhibition of photographs from the Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs, And They Called It Vancouver: Settler-Colonial Relationships to Indigenous Lands and Peoples. Ashlynn’s work on the exhibition was done as part of her 2020-21 Young Canada Works (YCW) post-graduate internship with RBSC. She is currently the Librarian & Archivist at the Vancouver Maritime Museum.

I first began curating this exhibition, And They Called It Vancouver: Settler-Colonial Relationships to Indigenous Lands and Peoples, in the autumn of 2020, almost exactly three years after my first exhibition of photographs from the Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. At that time, I was struck by how many items in the collection contained scenes of British Columbia that were familiar to me, even though most of them had been taken nearly a century before I was born, and my curatorial concept for that first exhibition, centered on the unchanging nature of architecture, gathering spaces, and natural landscapes across time.

When I dove back into the Uno Langmann collection this time, something quite different stood out to me. Although most of the images in the collection were taken approximately one hundred years ago, a mere blink of an eye on a historical scale, it seemed to me that many of the photographs were relics of their time, in the sense that they showcased scenes and themes with apparent pride that we today might see with a more critical eye.

An important note about the photographs in this exhibition is that, for the most part, we cannot be certain of the photographers’ intentions. Within the text of the exhibition, I take the liberty of hypothesizing about the purpose of the photographs – why someone at that time would have wanted to document wide swaths of forest that have been logged, or animals that have been killed for sport, or parades marching through downtown Vancouver. Without being certain of the reasons why these photographs may have been captured, these hypotheses are simply meant to express my own interpretation of the photographs, as I parsed through each and every one at the beginning of my curatorial process. I couldn’t help but witness the images through a lens that more critically examines the issues that so many of us care about today: the environment, the fact that we live on stolen lands, what it means to live in a post-industrial world.

The closer I looked at the collection, the more I seemed to find images that fell into one of those three categories. The knowledge of how these lands were stolen and the peoples indigenous to these lands brutally oppressed became the backdrop to how I viewed the entire collection and the exhibition. Images of trees being cut down and smokestacks being raised were not celebrations of burgeoning industry in a young province; they were examples of the destruction of the natural environment. Images of new buildings downtown and the creation of Stanley Park were not examples of progress towards modernization; they were examples of settlers confidently making grand plans for lands that did not and do not belong to them. Some of the images, no matter what their original purpose may have been, became visual evidence of a flagrant disrespect and disregard for Indigenous peoples.

In that sense, the photographers’ intentions in taking the photographs become moot. The purpose of the exhibition is not to uncover the original purpose behind the photographs, but to examine what the photographs can tell us – intentionally or unintentionally, consciously or subconsciously – about the ethos of the time, and how much or how little settlers considered issues like environmentalism, industrialism, and Indigenous peoples’ rights. What is in the photographs, and what is absent from the photographs, is in that sense equally important.

One of the strengths of historical photographs – and indeed, history in general – is that it can cause us to think more critically about our role in it. How have our pasts shaped us? How will we shape the future? I hope this exhibition encourages us, particularly those of us living on stolen lands, to think more critically about our own roles in the narratives presented here: our relationships to the environment, our relationships to urban development, and our relationships to and with Indigenous peoples. I hope we can more clearly see what’s there, as well as what may be missing.

No Comments

Archival Collaborations

Posted on March 22, 2021 @1:20 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger, Eva-Marie Kröller, Professor Emerita in the Department of English Language and Literatures, for contributing the below post!

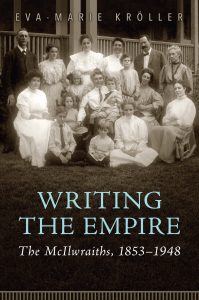

“Writing the Empire” is a collective biography of the McIlwraiths, a family of politicians, entrepreneurs, businesspeople, scientists, and scholars.

In the fall of 2014, I was in the throes of piecing together Jean N. McIlwraith’s career as writer and editor, for a book on her family now due to appear in spring 2021 as Writing the Empire: The McIlwraiths, 1853-1948 with the University of Toronto Press. I had been able to look through a bankers box full of McIlwraith’s papers held by the family, but while some brief periods in her life were thoroughly documented, there were others – and clearly important ones – about which little if anything had come to light. There was nothing, for example, on her collaboration with William McLennan on the historical novel The Span o’Life (1899) in the box, and on checking his files at my inquiry, Leslie Monkman – author of McLennan’s biography in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography – merely found a note to self with a question mark on it.

Under the circumstances, even individual letters like the one McIlwraith wrote in 1925 to Margaret Cowie, a Vancouver teacher who was collecting books and photographs for her school library, were a welcome find, but when I contacted UBC Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC) about this letter, I was not prepared to get a sensational email about a relevant new acquisition. The newly processed McLennan family fonds included the papers of author William McLennan. Among these was a sizeable folder primarily containing letters written from McIlwraith to McLennan between 1896 and 1897 during their collaboration on The Span o’Life.

My response was an unscholarly “WOW!,” and I was in the reading room of the RBSC as soon as I could possibly get there. The correspondence turned out to be extensive and as informative as I hoped it would be. There are many things to be said about these letters, but I will concentrate on a few aspects of literary collaboration illuminated by them.

The Span o’Life, one of several fictional renditions of the Battle of the Plains of Abrahams from a Jacobite perspective, is part of a late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century North American tradition in collaborative novels. As Susanna Ashton has shown in Collaborators in Literary America, 1870-1920 (2003), these productions could either serve as a gimmick to refresh tired novelistic techniques or they could be turned into serious debates of current concerns. The ne plus ultra of collaborative novels was The Whole Family, a Novel by Twelve Authors (1908), instigated by W. D. Howells, with Henry James as the best-known participant and Mary E. Wilkins Freeman as the most daring. As she has related in her memoir Three Rousing Cheers (1938), the harassed moderator of the collective was Elizabeth Garver Jordan, then editor of Harper’s Bazaar.

The connection between McIlwraith and McLennan or the reasons for their collaboration are not clear although the families may have known each other through the Great Lakes trade, and McLennan’s wife Minnie appears to have attended the Wesleyan Ladies’ College in Hamilton where Jean and her sisters were also students. The mutual esteem between these families is evident in these letters, and members were drafted to comment on everything from Scots idiom to the length of kilts to ensure authenticity in The Span o’Life. The authors also consulted with historians in Quebec such as the Abbé Henri-Raymond Casgrain whom Jean McIlwraith may have met on her own or through her brother-in-law John Holt of the Holt-Renfrew store. The role of moderator for The Span o’Life was played by McLennan’s brother, John Stewart, executive at the Dominion Coal Company in Boston and connoisseur of the history of Louisbourg. His services were needed because Jean McIlwraith was ferocious in defending her views of female agency, offering to “roll [her partner] in the snow or drop [him] in the ice for a cold bath,” along with other uncomfortable ministrations, if he did not give in to her emancipatory views (which, with his brother’s support, he mostly did not). In making a passionate pitch for female independence even if it was unhistorical for the eighteenth-century character of Margaret Nairn, McIlwraith anticipated Mary E. Wilkins Freeman in The Whole Family, who refused to shape the character of her chapter into a faded spinster as expected and instead turned her into a sexually alluring single woman in her thirties.

Contemporary reviews of The Span o’Life underscored that this was innovative work in historical romance, made all the more appealing because it was mildly risqué. As was often the case with collaborative work, most of the critical credit went to the better-known partner, in this case McLennan, but he negotiated an advantageous financial deal with Harper’s for Jean McIlwraith and, before his early death in 1904, provided generous support when she looked for work with a New York publisher. In addition, McLennan’s well-established credentials were useful in persuading Harper’s to commission illustrations for The Span o’Life from the Austrian Felician de Myrbach, whose work had previously appeared in books by Jules Verne, Alphonse Daudet, and Victor Hugo.

One of the poems in the novel was set to music by composer Frederick F. Bullard, with the rather ambitious goal that “the world will sway to the rhythm of the music.” A trained musician, McIlwraith was particularly interested in the role of music in their book, and one of several unexpected discoveries in these letters was the identity of her real-life voice teacher in McIlwraith’s story “A Singing-Student in London.” He was the unlikely-named tenor William Shakespeare, whom she transparently renamed as “Francis Bacon.” Shakespeare’s students readily recognized him and, because their own livelihood as voice teachers depended on having taken lessons with him, her criticism was vehemently discredited in the magazines. This, as she relates to McLennan, was one of several instances in which her impetuous indiscretions landed her in very hot water.

Without the arrival at RBSC of the McLennan family fonds, I would not have known about most of this background history and my book would have been the poorer for it. This brief review of literary collaboration would therefore not be complete without drawing out, once again, the crucial cooperation between researchers and attentive archivists.

No CommentsFraming memory

Posted on March 8, 2021 @10:13 am by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger, Barbara Towell, for contributing the below post! Barbara is University Archives’ E-Records Manager and an enthusiastic collector of antiques. This post continues an occasional blog series looking at 19th century photographs of women and their jewellery held in Rare Books and Special Collections.

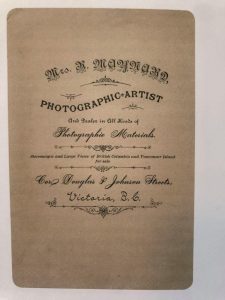

The art of framing memory: Hannah Maynard and the impossibly large brooch

Among the many items included in the Uno Langmann and Family Collection of British Columbia Photographs is this remarkable cabinet card created by Hannah Maynard, a 19th-century Canadian businesswoman, artist, and celebrated photographer. In 1862 Maynard’s business opened in Victoria in the Colony of Vancouver Island and remained in operation until 1912. Her clientele was said to be the well-heeled of Victoria, but as Dr. Jennifer Salahub tells us, Maynard photographed its inhabitants across economic classes (Salahub, p. 171). Maynard is most recognized for her experimental photography leaving her portraiture to be sometimes described as conventional. But in this image, I think Maynard achieves something quite unconventional. Crossing the boundaries of the photographic frame, something she is known for in her experimental photography, Maynard uses the subject’s jewellery to connect past artistic practice with the technology, and most importantly, the art of photography.In this cabinet card we see a portrait of a mature woman looking at the camera. She is dressed in black, wearing a ribbon bonnet, a watch chain, and an impossibly large brooch. The scalloped edge of the card stock suggests a time period of 1890s but the brooch is from an era prior. The pin was new around the time known as the Grand Period of Victorian jewellery (1861-1885). Fashion trends during the middle part of the 19th century favoured jewellery large in scale. Brooches were especially popular and were typically around 6.35 x 3.81 centimetres in size, roughly three or four times the size of pins popular in the period this photo was taken.

The brooch is known as a Swiss enamel. Drawing on a tradition centuries old, Swiss enamels were admired souvenir items handmade by highly skilled artists. The mid-century’s custom for large articles of adornment provided enamel artists ample scope to create a window framing an idealized time and place. They were status symbols of wealth and most importantly, Anglocentric class-based concepts of sophistication that could only be achieved through European travel. For affluent 19th-century tourists visiting Switzerland they made the perfect portable keepsake memorializing travel while signalling wealth and refinement.

Example of Swiss enamel showing colour saturation c1860. Photograph used with permission from Nelson’s Rarities.

What this cabinet card cannot show the viewer is the vibrancy of the brooch. Set against the black backdrop of the subject’s dress, the decorative frame, its saturated colours and impressive size would have made it the outfit’s focal point. And while I am unable to enjoy the colours of the pin 160 years later, I am still unable to keep my eyes off it. But this, I believe, is the central point.

Swiss enamels are very much part of a world before popular photography and it was specifically the new medium of photography that severely reduced the luxury tourist trade in Swiss enamels. In contrast to the Grand Period, brooch styles by 1890s had become comparatively small. This brooch is at least 20 to 30 years old at the time the photo was taken, even for a slow-moving colonial outpost such as Victoria, its inclusion seems somewhat odd; not old enough to be an antique, but not fashionable either. It is possible that the subject may have chosen this particular brooch herself without counsel from Maynard, however, photographic portraiture was a formal process in this period and the photographer’s use of visual support contextualizing the subject was common practice. The brooch’s position in the photograph effectively ties the subject to a bygone era. It is the key prop in this cabinet card and it is important that it be front and centre. The brooch’s centrality is the principle reason the bonnet is left untied, so as not to disrupt the viewer’s sight-line. The pin’s inclusion not only situates the subject in the past however, it also buttresses another narrative fundamental to Maynard’s contemporary artistic practice.

Most other cabinet cards use either the back or the block at the bottom of the card to advertise the name and location of the business. In this example the company information along with the words, photographic artist is printed on the back of the card. Maynard annotates the front of this card by hand, and that addition is unusual. She writes her married name, Mrs. Richard Maynard, and her occupation, Artist. Unlike other cabinet cards, Hannah Maynard presents herself not primarily as a photographer, but instead she signs the work as an artist. Maynard used her subject’s gender, age and symbols of class-based sophistication as a backdrop and canvas to draw a line connecting past artistic methods of recollection, as seen with the Swiss enamel, with the artistic and technical practice of photography. Maynard uses the brooch to bridge a conceptual relationship to photography but not to privilege the technology over the human hand. Instead she stages for the viewer a meeting between the artistry and status symbols of the past with the new techniques of portrait photography. In doing so she illustrates for us a lineage of remembering where the primary and central role belongs to the artist.

Works Cited

Salahub, Jennifer. 2012. “Hanna Maynard: Crafting Professional Identify.” In Rethinking Professionalism: Women and Art in Canada 1850-1970, edited by Kristina Huneault and Janice Anderson. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press. https://www-deslibris-ca.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ID/443449

Wikipedia. “Cabinet Card.” Accessed Dec 29, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cabinet_card

No Comments

Remembering Jim Wong-Chu

Posted on February 3, 2021 @12:42 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Brandon Leung for contributing the below post! Brandon is a graduate student in the Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management program at Ryerson University and completed an archival internship with Rare Books and Special Collections in December 2020.

A few years ago, I had what turned out to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity at Rare Books and Special Collections. During my time as an undergraduate at UBC, I took a class about archives that had us visit RBSC every week to look at a different collection held there. One time, we had the chance to actually hear from one of the donors themselves, the late Chinese Canadian artist and activist Jim Wong-Chu. During that class, he talked continuously, without pause, about Chinese Canadian activism and history, an ability he was well known for. Afterwards, he showed us an album, titled Pender East, that contained both photographs and handwritten poetry. As a student who was, and still is, interested in the intersection of text and photography, this album amazed me. The photographs were skillfully printed, depicting people and places in Vancouver’s Chinatown, while the poems spoke about the Chinese Canadian experience. I would come away from this class with the album still on my mind and it unknowingly became the first and last time I would see Jim Wong-Chu in person. A couple of years later, I would find out that he unfortunately passed away. Yet Pender East still remained on my mind enough that over this past year, I decided to write about it for my final thesis paper for Ryerson University’s Film + Photography Preservation and Collections Management program, done alongside an internship at RBSC. In the following blog post, I would like to talk about some discoveries I made along the way. Though the COVID-19 pandemic hit in the middle of my research, I fortunately still found out several things about the album from a variety of sources, including Jim Wong-Chu’s fonds, YouTube videos of him and individuals who knew him personally.

Jim Wong-Chu, Pender East, photographic album, [after 1970?] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

One interesting fact I discovered about Pender East was that it was partly a collaborative work, which fit into the community-based activism that was going on at that time. For example, the poems included in the album showcase this. Though Jim Wong-Chu wrote many of the poems (a few which would appear in his later poetry book, Chinatown Ghosts), one about a grass dragon performance was written by his friend and fellow Chinese Canadian cultural activist Paul Yee. Additionally, the poems as they appear in the album were handwritten by another one of his friends, Cynthia Chan. Both Yee and Chan are named in the album’s final acknowledgement page, though the nature of their contributions isn’t revealed in the album itself. Fortunately I was able to speak with both of them and learned about their contributions.

Information about photographic prints, especially prints made in the pre-digital age, can also be found in contact sheets and film negatives. The Jim Wong-Chu fonds contain a large amount of these materials and I was fortunate enough to go through a box of them. One thing that can be said about archival materials is that they provide material evidence of the past and this box of negatives and contact sheets provided material evidence for some of the things I was learning about Pender East.

By looking at these materials, I was hoping to find some of the photographs in Pender East within these contact sheets. Contact sheets are helpful documents of a photographer’s practice because they show single rolls of film on one piece of photographic paper. We can then assume that all the photographs on one contact sheet were photographed in close proximity to each other. For example, I found the following photograph of a man standing in front of an election campaign headquarters in one of Wong-Chu’s contact sheets (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2740).

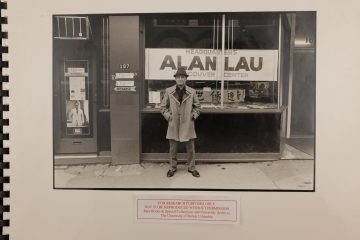

- Jim Wong-Chu, [Chinese man standing in front of Alan Lau headquarters] from Pender East, gelatin silver print, [after 1975] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

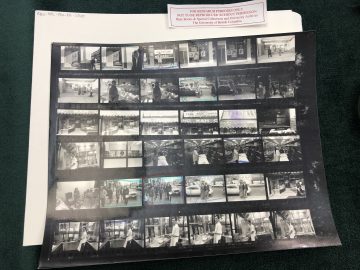

- Jim Wong-Chu, [East Pender street contact sheet], gelatin silver print, [after 1975?] (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2740, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 33)

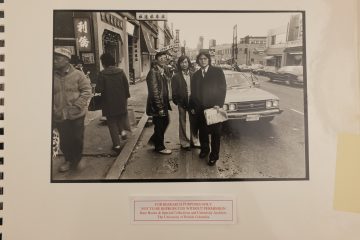

I also discovered that this specific contact sheet contained a majority of images that were included in Pender East. By looking closely at the photographs, and from what interviewees told me, I was also able to figure out where some of these photographs were taken. The above photograph was taken at 107 East Pender Street (seen in the photograph), while a photograph of three men posing on the street that appears later on the contact sheet was taken in the 200 block of East Pender, a known commercial hub of Vancouver’s Chinatown at the time (as identified by interviewees). This material evidence of Jim Wong-Chu’s photography and his photographic practice corroborated what I had been told in interviews, that he spent many days walking through Chinatown, up and down East Pender Street, and photographing.

Jim Wong-Chu, [Two unidentified men and Charles Mow] from Pender East, [after 1975] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

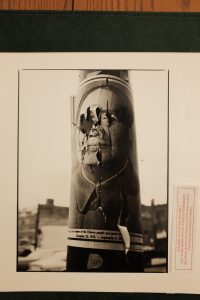

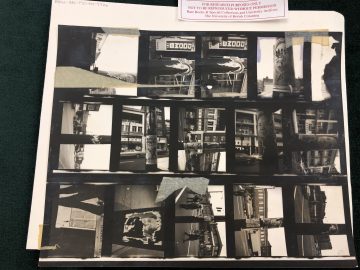

Another striking image in Pender East appears halfway through the album. It is a close-up of a poster of Mao Zedong, leader of the People’s Republic of China, torn at the eyes, pasted onto a street pole in Chinatown. Through my research, I also discovered this image corroborated another story related about the Chinese Canadian community. In a video recording of a poetry reading Jim Wong-Chu did at the Roedde House Museum, he discusses the story behind this photograph. After Mao died in 1976, supporters of the People’s Republic of China put up posters depicting him around Vancouver’s Chinatown. Soon after, supporters of the opposing Kuomintang government (The Chinese Nationalist Party, based in Taiwan, who claimed to be the rightful rulers of China) tore up the posters and Wong-Chu photographed the results. Wong-Chu also decided to use this photograph on the cover of the first edition of his poetry book Chinatown Ghosts, which he said drew the ire of both camps. In his fonds, I found a contact sheet containing the image in question, plus photographs of other torn Mao posters throughout Chinatown (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2766). Again, his contact sheets acted as material evidence of Chinese Canadian history and, alongside Wong-Chu’s own story, gave me insight into another side of the community that I would not have known from Pender East itself.

- Jim Wong-Chu, [Torn poster of Mao Zedong] from Pender East, gelatin silver print, [after 1976] (RBSC-ARC-1710-31-14, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 41)

- Jim Wong-Chu, [Mao posters contact sheet], gelatin silver print, [1976?] (RBSC-ARC-1710-PH-2766, Jim Wong-Chu fonds, box 33)

By the end of my research, I had made many more discoveries about the Chinese Canadian community and Vancouver’s Chinatown in the 1970s, too many to be fully listed here. Of course there are many more to be made and I hope my work so far can act as a stepping stone into more research for one of the most accessed collections at RBSC. I feel privileged to have been given the opportunity to work on Pender East, learning more about Chinese Canadian history and Vancouver’s Chinatown and helping stoke some old memories.

(Through all my scrutiny of the photographs in Pender East, from my interviews and other archival photographs of Vancouver’s Chinatown, I also created a Google “My Maps,” pinpointing some of the locations where Wong-Chu’s photographs were taken.)

No CommentsPicturing time

Posted on January 6, 2021 @1:44 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger, Barbara Towell, for contributing the below post! Barbara is University Archives’ E-Records Manager and an enthusiastic collector of antiques. This is the first post in her occasional series on jewellery pieces worn in historical cabinet card portraits.

Popular complications: telling the time

I can pinpoint the moment my love-affair with the past began. It was the day a trunk was moved from my grandmother’s house in New Westminster to our basement in Burnaby. The chest was the curved-top variety lined with cedar with a large bottom drawer. How long it sat in the basement before I uncovered its secrets, I cannot tell you, likely hours, not days. The weight of the lid…the squeak of the hinges…the smell of the cedar; that was the moment.

Item zero: watch found in cedar trunk. Fitted case not original to the watch. Image credit: Barbara Towell

The bottom drawer was where the treasures lay. The passage of time had dried out the wood, to open it I had to pull one side of the drawer then the other inch by inch. When I got it open, I saw hundreds of photographs. I expected to recognise my grandparents, my father, or my uncles, but in photo after photo I did not know a single person. Over the days, months and years I made my acquaintance with each and every face. Sitting in the basement studying the faces stored in the bottom drawer was a favourite childhood pastime. But the photographs were not all the trunk contained, there was another item hidden amongst the trunk’s contents: an old watch.

Sometimes I am asked about the first item in my collection of old things. Perhaps because I can recall the particular transaction so clearly, I have always answered that it was a Czechoslovakian glass and brass necklace from the 1920s bought for $12.00 at a shop called the Blue Heron. It is only in writing this blog that I realize the watch uncovered in the cedar chest that day when I was 11 years old was actually item zero.

I tell you this story because old photographs and jewellery introduces a series of blog posts I am writing looking at cabinet card portraits of women and the jewellery they wore. In these examples the ornaments displayed hold a central role in the images’ composition and meaning.

Originally shot by Van Alstine photographers Red Oak, Iowa, the photo is part of the Uno Langmann and Family Collection of British Columbia Photographs. Cabinet cards gained popularity in the 1870s and 1880s and were an accepted and affordable method of portraiture. One can locate many such examples in this period of (primarily white) women in black clothes wearing a watch on a long chain. Dr. Annie Rudd describes this kind of portraiture as the social media of the 19th Century (Rudd, 2015). Rudd sees the carte de visite, a smaller precursor to the cabinet card, as a “socially sanctioned and standardized mode of self-presentation” (Rudd, 2015) and because both the carte de visite and the cabinet card were designed to be shared they helped shape cultural standards through their distribution.All we can see of the woman’s outfit is a black button-down bodice and an odd-looking pocket sewed onto the front of the outfit. The pocket has not been sewn on straight, the right side is higher than the left. One cannot mistake the quality of the material and perfectly close fit of her bodice so why is the pocket sewed on in this way? Part of the answer is that the pocket holds a watch. Watches were very popular all through the 19th Century and women in the last quarter wore their watches one of three ways:

- tucked into a belt or a fit-for-purpose pocket at or near the waist;

- at the bodice hanging from a brooch watch chatelaine; or

- as we see in this photo tucked into a crochet or lace pocket angled with the right side higher than the left.

But why? The answer is for practical ease of access. The subject is right-handed and it is simpler for the right hand to take the watch out of the pocket on the left if the pocket is slightly angled. It would stand out more to viewers contemporary with the period if the crocheted pocket wasn’t angled. In all three cases the watch hung from a long chain called a muff or guard chain which was typically 154.4 centimetres in length (Cummings, p. 95).

The guard chain in the Van Alstine cabinet card is doubled under the chin drawing the viewer’s eye toward the face. Given this is a portrait the brooch and chain’s placement near the throat makes sense; it emphasizes the subject. Her appearance is not all we are meant to see; the draping of the chain draws the viewer’s eye to the crocheted pocket. The angle and texture of the pocket emphasizes the timepiece within suggesting action, functionality and matter-of-fact practicality on the one hand, and a modicum of affluent comfort on the other. If highlighting the face is the point of the portrait, the watch functions as a balancing counterpoint. Everything included in the cabinet card’s field of view was made by choice. The passage of time has undermined the clarity of photograph’s message, but her outfit and the simple yet meticulous construction of the image communicates middle class propriety and tasteful prosperity.

Cabinet cards typically include an advertising block containing the name and location of the business; indeed, advertising was one of the main objectives of the medium. They also promote a “carefully calibrated self-presentation” of the subject (Rudd, 2015). The assembly of clothes, hair and pocket watch work together as kind of visual shorthand for respectable middle-class conventionality. The actual material conditions in which this woman lived are unknown to us, but through the composition of the photograph we are led to believe that she has a comfortable life with places to be and appointments to keep!

Works Cited

Rudd, Annie. 2015. “Public Faces: Photography as Social Media in the 19th Century.” The International Center of Photography, Aug. 27, 2015. Accessed Dec. 26, 2020. https://www.icp.org/perspective/public-faces-photography-as-social-media-in-the-19th-century

Cummins, Genevieve. 2010. How the Watch was Worn: A Fashion for 500 Years. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club Publishers.

No Comments

Exploring Barrowclough’s postcards

Posted on December 18, 2020 @2:48 pm by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Brandon Leung for contributing the below post! Brandon is a graduate student in the Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management program at Ryerson University and has just completed an archival internship with Rare Books and Special Collections.

In the beginning of my internship at RBSC, I was able to first work on the Chung Collection, which I was interested in for its materials related to the experience of Chinese people in Canada. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 this project was put on hold as well as my internship. Fortunately, I have been able to continue my internship in the past few months with a new project involving the Uno Langmann Family Collection of BC Photographs, a primarily photographic collection. Given my background in photographic history, I was tasked in identifying the various photographic processes contained within the Langmann collection. Of course, because of the present circumstances, I had to rely on the photographs that have been digitized so far for my work, which is less than ideal (so many physical details can help you identify a photographic print!). Nevertheless, it still gave me the opportunity to look through a large amount of the different kinds of historical photographs held in the Langmann collection.

Flipping (virtually) through the myriad of photographs, I came across a series of postcards, one of many series of postcards in the collection, that were created by a specific photographer named George Alfred Barrowclough. According to Breaking News: The Postcard Images of George Alfred Barrowclough (2004) by Fred Thirkell and Bob Scullion, Barrowclough was born on May 1, 1872 in Birkenhead England. He immigrated to Canada with his family in the 1880s where they settled in Winnipeg. By the 1890s, he began working as a photographer and in 1904 opened his first photographic postcard business. In 1906 he moved in with his brother in Burnaby and even went down to San Francisco to photograph the ruined city after the recent earthquake. By 1909 he was living in Vancouver. The majority of his BC postcards were made from 1908 to 1912.

Barrowclough’s postcards piqued my interest for various reasons: one, I have become interested in historical “real photo postcards” (photographs printed onto photographic paper with postcard backings); two, most of the postcards in the Langmann collection are either created by photographic printing companies or unknown photographers (though other identified photographers come up such as Leonard Frank and Phillip Timms); and finally, many of Barrowclough’s postcards are different from what one might expect of postcard imagery. Many of his postcards do depict the usual touristic fare (city views, prominent buildings, Stanley Park), but, of interest to me, some of his photographs seem to have been taken surreptitiously or are subjects you would expect from a photojournalist. For example, a few of his postcards depict the aftermath of a streetcar crash into a drugstore and crowds viewing a Barnum and Bailey Circus parade in Vancouver (UL_1624_03_0040 and UL_1624_03_0043).

- George Alfred Barrowclough, A bad smash between a drug store window and st. car, Vancouver, B.C., [between 1910 and 1920?], gelatin silver print (UL_1624_03_0040, Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs)

- George Alfred Barrowclough, Carnegie Library, Vancouver, B.C., [between 1910 and 1920?], gelatin silver print (UL_1624_03_0043, Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs)

There was one of Barrowclough’s postcards that I came across which brought up some questions and associations for me. The postcard in question is titled Hindu Immigrants, Vancouver, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0052). In it, we see a group of turbanned South Asian men in front of a train station by the Vancouver waterfront (there is a ship in the background). Some of the men hold bags or packs. Others can be seen loading their belongings onto a nearby horse-drawn cart. We can tell the photograph was taken clandestinely; no one appears to notice Barrowclough. The photograph is composed at an angle, as if it were taken quickly and sneakily. Other observers seem to be present; besides Barrowclough himself (and now us looking at the postcard in the present), a blurry man can be seen to the far left in a suit and straw boater hat.

George Alfred Barrowclough, Hindu Immigrants, Vancouver, B.C., [between 1910 and 1920?], gelatin silver print (UL_1624_03_0052, Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs)

Photographic history can give us an answer. Photography has been used to depict the “other” (oftentimes non-White individuals) throughout its history. Rising in tandem with 19th century European imperialism, photography was used to photograph colonized peoples as scientific specimens or entertaining spectacles for European audiences. As photography came soon after to what is now called North America, it was also used to extend the colonial gaze onto Indigenous and Native American populations.

In the early 20th century, when Barrowclough made his postcards, American photographer Lewis Hine took photographs of newly arrived immigrants in Ellis Island, New York to document the conditions there; German-American photographer Arnold Genthe took candid photographs of San Francisco’s Chinatown with an Orientalist and sentimental aesthetic. In Canada, Indigenous people would ask to be paid for European photographers’ use of their image, highlighting the power dynamics between photographer and subject. This relationship can also be seen in Barrowclough’s postcard. His subjects do not seem to be aware of being photographed, yet their image and status as “immigrants” were definitely being used and sold. Not many of Barrowclough’s other postcards depict the trade in images of Indigenous people, but the sentiment remains. White photographers and consumers of photographs and other visual imagery were interested in depictions of those different from themselves.

George Alfred Barrowclough, Where 23 Japs lost their lives in G.N.R. wreck, Nov. 28, 09, near New Westminster, B.C., 1909, gelatin silver print (UL_1624_03_0123, Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs)

This colonial gaze is not just apparent from how Barrowclough photographed these men, but also from how he titled the postcard, Hindu immigrants. Likely the men are Sikhs because of the turbans they wear, called “Dastaar” in Sikhism. Sikh immigrants are well known for their early role in British Columbia’s economy, especially as workers in wood mills. Yet to European observers, anybody from India is a “Hindu.” All Chinese immigrants were “Chinamen.” In a more sensationalist postcard, Barrowclough photographed the aftermath of a train crash and freely used a slur in its title: Where 23 Japs [sic] lost their lives in G.N.R. wreck, Nov. 28, 09, near New Westminster, B.C. (UL_1624_03_0123) Language reveals the attitudes of the time and the fraught relationship between “settlers” and “immigrants.” Of course, these relationships were all happening on what was, and is, First Nations land.

Canada’s creation as a “White man’s land” and Canadian immigration history also play an important part into how we read this image. Examples of Canadian immigration policy of the early 20th century reveal the power dynamics at play in this kind of looking. In 1885, the Canadian government implemented an immigration policy popularly known as the Head Tax. It forced Chinese immigrants to pay upwards of five hundred dollars to enter the country. By 1923, the Head Tax was replaced by the Exclusion Act that barred almost all Chinese immigration.

The postcard also reminded me of another incident in Canadian history, also related to South Asian immigration. In 1914 the passengers of the ship the Komagata Maru, many of whom were Sikhs, tried to gain entry into Canada through Vancouver. They challenged two existing laws aimed at stopping immigration from India, one barring immigrants who did not travel on a “continuous journey” by ship and the other barred immigrants who had under two hundred dollars in savings. Both laws were instituted in 1908, overruled, but then reinstated by 1914. Photographs of the Komagata Maru, its passengers, government agents inspecting the ship and on-shore onlookers also exist, but this passing interest in these South Asian immigrants also did not benefit them. After about a month in Vancouver’s harbor, the Komagata Maru was forced to turn back. Some of its passengers were met with deadly force from British Officers upon their return to India.

Photographs are never just pictures, just as archives or collections are never neutral. Images are a construction of the time period they were created in. Even the most innocent-looking or everyday images can tell us more about their creators or remind us of how loaded with meaning and connotations they are. Coming across an image like Hindu Immigrants reminds us of the history of this unceded land and the people who have passed through it.

No CommentsGhost Towns in British Columbia

Posted on December 7, 2020 @11:11 am by cshriver

Many thanks to guest blogger Emily Homolka for contributing the below post! Emily completed her MLIS degree from UBC’s iSchool (School of Library, Archival and Information Studies) in May 2020. She is currently project archivist for the Nilekiwe Yesilawiwaci Sharing History project with the Shawnee Tribe Cultural Center.

I’m very pleased to introduce my digital exhibit, Ghost Towns in British Columbia, curated using some of the archival and historical holdings of Rare Books and Special Collections!

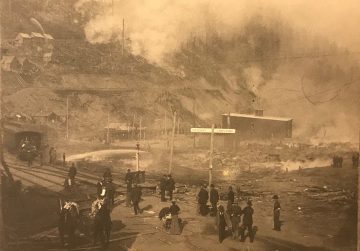

Ghost Towns in British Columbia explores some of the themes of emergence, daily life, and sudden (or eventual) disappearances of towns in British Columbia, looking briefly at the rise and decline of Anyox, Phoenix, and Sandon. Through those towns and through the holdings of RBSC, this exhibit looks at the broader phenomena of ghost towns, considering their connection to history, memory, and memory institutions, such as libraries, museums, and archives.

I first became interested in the idea of ghost towns in 2019, when I spent the summer working with a project called “Digitized Okanagan History” (since rebranded as British Columbia Regional Digitized History), which digitizes local archival and historical materials in Kelowna, a city in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia. As I worked, I would often come across photographs of towns that, when I searched for them, would only show up in a Wikipedia page about ghost towns in British Columbia or briefly mentioned in a travel pamphlet. I became fascinated with the idea that I was seeing a glimpse of a place that no longer exists, and that I would not have known ever existed before I found traces of them buried in the archives.

Ghost towns are by their very nature ephemeral, there and then gone, sometimes leaving behind scant amounts of information or the remains of building, sometimes getting repurposed (for good or for ill) decades after the end of the town, sometimes leaving behind nothing at all except memories and a romantic notion of what the town used to be. Exploring the collections at RBSC to see what information has been left behind and thinking about how that information shapes the modern day understanding of ghost towns has been an incredibly rewarding and fascinating experience. Through my exhibit, I hope I show what it is about ghost towns that has so captured my own imagination and to spark a similar interest in my readers!

I hope you enjoy the exhibition Ghost Towns in British Columbia!

This exhibit was possible due to the feedback and support that I received from Erik Kwakkel and Chelsea Shriver, as well as Rare Books and Special Collections at UBC Library that was so generous with my use of the archival materials. Thank you also to the Uno Langmann Family and to Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung, whose donations made this exhibit possible.

No CommentsPersonal archives show & tell (VIII)

Posted on October 27, 2020 @2:45 pm by cshriver

Show and Tell: Selections from our Personal Archives and Libraries

How we remember, and what we hold dear, differs from person to person. All of us have personal archives we keep to preserve memories that are precious, that document our families, our histories and record important events. It could be a simple piece of ephemera we love and cannot part with (a ticket stub from our first concert, for example), or photographs of ancestors that offer clues to our origins, or anything we have set aside and saved for a myriad reasons. Similarly, our personal libraries hold volumes that have emotional value to us, not just for the words contained in it, but as a reflection of a time in our lives, we found them particularly relevant. This could be the first book of poetry that made us fall in love with verse, or the dog-eared copy of a classic novel that led us to our current passion for libraries and library work. This blog series explores selections from the personal libraries and archives of members of the Rare Books and Special Collections team, and other colleagues from UBC Library and beyond. We hope our stories will help you reflect on what is meaningful at this time in your, and in our, collective histories.

— Krisztina Laszlo, Archivist

Ashlynn Prasad, Archives and Reference Assistant, RBSC

As a young professional acquainting myself with archives, it actually took me a long time to understand the ways in which the archival world had already touched my personal life. I started working in an archives at the age of 18, at which point older cousins of mine had already been entering what I would come to understand as archival spaces for years. They were undertaking a genealogical research project that would hopefully uncover who we were, who our ancestors had been, and where we all came from.

The information that had travelled down through the generations about our family history was minimal at best: we knew that my great-grandparents’ generation had migrated to Fiji from India in the late 1800s. We knew that they had been indentured labourers for the British Empire, who held control of India at that time and were looking for a labour force to work the land in Fiji, another place they had colonized. The list of things we didn’t know was much longer: the names of our ancestors who had originally migrated, the name of the ship they had come over on, where in India they had come from, why they had chosen to leave their home for a difficult life of farming on a remote island nation that was fraught with sometimes violent tension between the colonizers and the indigenous community – and the list went on. Theories abounded in our family, particularly over the latter question. Our theories were mostly romanticized stories that we told ourselves, about ancestors who had fled India, perhaps to escape arranged marriages, with a secret lover, in hopes for more freedom in Fiji.

Research on the part of my cousins and other Indo-Fijian scholars has provided us with a vision of the past that is slightly less rosy. In recent years, the term “indentured labour” has come to be understood as little better than debt slavery. And while we had assumed that our lack of information about our ancestors was due to an intentional effort on their part to hide information about themselves, it now appears that the true reason is due largely to the poor record-keeping practices of the British.

A further complicating factor has been the fact that naming conventions among the Indo-Fijian community are different than what we in western society are accustomed to, and what the British record keepers would have expected. In Indo-Fijian society, there is no such thing as a family name. Siblings will often all have the same last name, but it won’t be the same name as their parents. Because of this, it is nearly impossible to track lineage through a family name. And because the British record keepers didn’t understand this, there is nothing in the records of Indo-Fijian immigrants to tie generations of one family together.

This is what has made the search for our family’s origins so challenging. The search has been a piecemeal collaboration of whatever information we can find. It has included scraps of records that we were able to find using the information we already had, such as the birth certificate of my maternal grandfather pictured above.

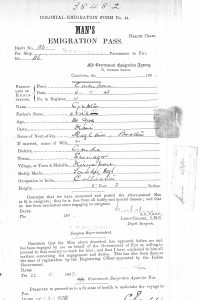

It has also included records that were painstakingly dug up from the notoriously restrictive Fiji National Archives. In one instance, my cousin began undertaking research in the archives, equipped with the name of my mother’s paternal grandfather – he had dropped his first and middle names and simply went by his last name, “Gupta” (written by the British as “Guptar”). My cousin was able to narrow down his search to two possible records, but reached an impasse because he had no further information about our great-grandfather. The only way he was ever able to figure it out was by calling upon the help of the rest of the family: my mother, her ten siblings, and the twenty-eight cousins in my generation. It turned out that, years before, a great-aunt had visited my parents, had told a few stories and happened to mention the name of a village in India, which my mother had happened to make a note of. That piece of information allowed my cousin to narrow down his search to the record you see here: my great-grandfather’s emigration pass, which tells us his father’s name, his age when he migrated, his brother’s name, the specific area in India he came from, his occupation, and – perhaps most interestingly – his caste.

In some ways, the moral of the story had been in front of me for years before I even knew what an archives was: good record keeping matters.

No Comments