Intrepid Sisters on the Move II

Posted on December 24, 2025 @10:49 am by Chelsea Shriver

Many thanks to guest blogger, Barbara Towell, for contributing the below post! Barbara is E-Records Manager with Digital Programs & Services at UBC Library and an avid cyclist.

This blog is part two of Kitty and Clara Wilson – Intrepid Sisters on the Move. If you have not read part one, please find it here. In this part I plan on comparing spots Kitty and Clara saw on their ride with those same or similar spots today.

The Rides in Context

Kitty and Clara were already local Vancouver celebrities when they began their cycling tour up the coast of Vancouver Island to Campbell River. In 1936, eighteen months before the first of their Vancouver Island trips, they achieved what every penny-pinching backpacker dreams of: they talked their way onto the British Steam Ship Harmatris, a merchant tanker headed for Australia, securing unpaid employment (in return for passage) as deckhands. They did jobs such as cleaning and painting. This was the first of many merchant tankers on which they sought, and received, passage to their next destination. Their first port-of-call was Melbourne, then on to Tasmania, Australia; Durban, South Africa; Dublin, Ireland; then finally, London England where they planned a cycling trip around the United Kingdom.

In London, they bought second-hand bikes, probably Rastus and Ginger and tried to teach themselves to ride them. Imagine planning a cross-country cycling trip without knowing how to ride a bike? After a few failed attempts and bloodied body parts they agreed, “we will try to learn to ride these just once more and if we crash this time we will sell the bicycles and walk around England” (Vancouver Sun, Dec. 12, 1936). Finally their bikes stayed upright and they embarked on their first cycling tour around the England and Scotland. In 1938 they returned to Vancouver via Panama. Once back in Vancouver, Clara gave talks to women’s groups and interviews to newspapers about their unique and, economical way of seeing the world. Clara always emphasized the thrift of this around the world adventure.

Their cycling travels continued in BC over the next decade. They rode each summer and documented their trips in the photo albums held at Rare Books and Special Collections. What I discovered on our recreation of their trip is that very little of what Kitty and Clara documented in the album and letters home survives – maybe just the road and the ocean, but joy endured, across time, across cyclists.

Nanaimo

- Nanaimo, B.C. Business Section. British Columbia Postcards Collection (SFU Library Digital Collections). MSC130-4069

- Site of the old Plaza Hotel. Photo courtesy of Barbara Towell

Qualicum

- Broken eggs, Qualicum. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1591_0185

- Clara, Wings’, Cabin #9, Parksville. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1591_0002

- Qualicum Beach. Photo courtesy of Barbara Towell

Parksville

- Rd. to Parksville. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1591_0113

- Road to Parksville. Photo courtesy of Barbara Towell

Campbell River

- Lunch at Danby’s A.C. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1591_0080

- Potential location of Danby’s Auto Camp. Photo courtesy of Barbara Towell

Campbell River

- Campbell River pier. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1591_0195

- Location of public dock. Photo courtesy of Barbara Towell

Elk Falls

- Elk Falls. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1591_0072

- Elk Lake. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1591_0106

- Elk falls today. Photo courtesy of Barbara Towell

No Comments

Intrepid Sisters on the Move

Posted on July 9, 2025 @2:38 pm by Chelsea Shriver

Many thanks to guest blogger, Barbara Towell, for contributing the below post! Barbara is E-Records Manager with Digital Programs & Services at UBC Library and an avid cyclist.

On Monday, July 17, 1939, twenty-something sisters, Clara and Kitty Wilson, left their comfy family home on the west side of Vancouver and embarked on a two-week self-guided cycling holiday to Vancouver Island. This journey was one of a decade of summer cycling tours they undertook in British Columbia. They documented their trips through a series of photos and letters home that have been brought together in a wonderful photo album, now fully digitized and available on UBC Library’s Open Collections and forming part of the Uno Langmann Family Collection of Photographs. For Kitty and Clara Wilson, the summer of 1939 was one of leisure, adventure, letter-writing, and fun.

86 years after Clara and Kitty’s trip, my partner and I plan to recreate that ride, tracing the sisters’ tire marks, staying in the places they stayed, seeing the sights they saw. Our tour, like many of Kitty and Clara’s, begins at the Plaza Hotel in Nanaimo (now called Fairmont Hotels and Resorts), and carries on north to Campbell River. Some of the hotels and camps where Clara and Kitty stayed still exist, but most are gone. All the natural monuments remain however, and we plan to visit the waterfalls, rivers, and maybe the potholes mentioned in the letters. As for the buildings, I hope to find at least the addresses of where these places once were. In short, we plan to do just what Kitty and Clara did all those summers ago: enjoy a journey powered by legs and bicycles.

The Route

Kitty and Clara began their ride on July 17 and arrived in Campbell River on July 23, 1939. Their trip took place along what is now known at Highway 19A Ocean Side Route, which was at the time, primarily a gravel road. The highway was only fully paved in 1953, as part of WAC Bennet’s highway improvement plan. The sisters averaged just over 40K per day; theirs was a leisurely pace. Kitty herself said it best in a letter home: “We walked up every hill that was more than a foot high and still made good time.” I like the attitude conveyed in the letters; some days they just didn’t feel like riding, especially once they got to Campbell River where they were spoiled by the proprietor of their lodgings, Mr. Danby. They were on holiday after all.

The Gear

We don’t plan on sourcing and riding the same kind of bikes Kitty and Clara used (this isn’t that kind of recreation), but judging by the photographs, the sisters appear to be riding 1930s Dutch-style bikes that weigh-in at more than 20 kilograms each. They named these bikes Rastus (Clara), and Ginger (Kitty).

Kitty and Clara did not itemize their gear, but I can see from the photos that they traveled light: one small suitcase each strapped on to their bike’s luggage rack. Given the heft of Rastus and Ginger, packing light was necessary. I believe they brought their bikes on the ferry that docked at what is now Canada Place in Vancouver then took the CPR Princess Elaine to Nanaimo. It would be another twenty years before BC Ferries established the same routes to Nanaimo.

The Lodging: Auto Camps

There are still evidence of tiny cabins dotting the seaside on Vancouver Island. They were an invention that developed together with the expansion of the road network. I never knew what an auto camp was before I started reading the letters, but in 1939 they were everywhere. The sisters wrote to the proprietors of the auto camps along their route in advance ensuring they had a place to stay.

The Letters

Kitty and Clara wrote and received letters from their family daily, care of various post offices along their route. To the 21st century reader, the sisters’ address and the manner in which they write paints a veneer of white British middle-class privilege and youthful ease. Their letters are full of comic misspellings, nicknames, and devil-may-care kinder-pomp. In contrast to the casual and nonchalant attitude taken up in the letters, the sisters planned this trip carefully. Two young women cycle-touring the dirt roads of Vancouver Island was not a common sight in 1939, and the people they told had opinions about their adventure. The sisters maintained an attitude about their trip that strikes me as particularly modern; they didn’t seem to be especially influenced by people’s opinions of how to spend their leisure time.

These two were not ordinary.

I hope you will join me in part two of this blog as we recreate the ride Kitty and Clara embarked upon 86 years ago, compare the sights, and perhaps get to know these intrepid sisters just a little.

No CommentsChung | Lind Gallery summer hours

Posted on June 16, 2025 @8:39 am by Chelsea Shriver

Due to staffing changes, the Chung | Lind Gallery will have reduced hours for summer 2025.

Due to staffing changes, the Chung | Lind Gallery will have reduced hours for summer 2025.

The planned summer opening hours are:

- June 17-28, 2025: Closed

- July and August, the Gallery will be open Wednesdays to Saturdays from 10 am-5 pm

As opening hours are subject to change, please check the hours portal for the most up-to-date information.

During our reduced hours, we will have limited availability for guided tours and class visits.

We invite you to enjoy our audio highlights tour, our audio guide, or our 360-degree virtual tour. You can also browse digitized materials from the Chung and Lind Collections, and enjoy stories from the Chung | Lind Gallery Blog.

If you have any questions, please feel free to contact us through the RBSC contact form or by sending an email to rare.books@ubc.ca. Thank you again for your understanding and interest in the Chung | Lind Gallery!

No CommentsIt’s the Cream of the Crop!

Posted on June 9, 2025 @1:39 pm by Jacky Lai

Many thanks to guest blogger Gabriella J. Cigarroa for contributing the below post! Gabriella is a graduate student at the UBC School of Information and recently completed a Co-op work term with Rare Books and Special Collections Library.

It’s the Cream of the Crop!: The B.C. Dairy Historical Society Collection

As a Co-op Project Archivist in Fall 2024, I processed the B.C. Dairy Historical Society collection. Since 1998, the B.C. Dairy Historical Society (BCDHS) has collected a breadth of records documenting the history of the provincial dairy industry. Used to write books including Jane Watt’s Milk Stories: A History of the Dairy Industry in British Columbia, 1827-2000 and High Water: Living with the Fraser Floods, this collection includes a wealth of journals, photographs, and records from provincial dairy organizations and producers. Materials originated from the Fraser Valley Milk Producers’ Association (now known as Agrifoods, and owners of Dairyland until 2001), Palm Dairies (a dairy local to Vancouver that was bought by Dairyland in 1989), and assorted dairy industry professionals and enthusiasts.

Some photos of my favorite finds in the collection are shared below:

RBSC-ARC-1875-AR-04: St. Charles Evaporated Cream [cow-shaped clock]

RBSC-ARC-1875-AR-07: [Movie camera and attachments]

A movie camera owned by Neil Gray, who was a driving force in the B.C. dairy industry as a previous General Manager for the Fraser Valley Milk Producers’ Association, Director of the National Dairy Council of Canada, President of the B.C. Dairy Council, and member of the B.C .Dairy Historical Society.

RBSC-ARC-1875-SPLP-07 – Approaching Prospects. One of two LPs from the 1940s, records of salescasts presented by the Milk Industry Foundation that were used to evaluate and teach dairy salesmen. Each is a one-of-a-kind reference recording, used to test the master recording before making copies to distribute.

As of 2023, dairy was the top agricultural commodity in B.C. This collection documents the work of dairy co-operatives, producers, and other industry professionals to develop that market.

If you think about us the next time you visit the dairy aisle at your local grocery store, please contact RBSC about making a research visit.

No CommentsQuon On: A Legacy of Travel, Trade, and Community in Chinese Canada

Posted on April 26, 2025 @12:21 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is part of RBSC’s blog series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

Mar June, center to the direct right of man in light suit. Mar Yee Why to the left of the light suit. Ma Wah Kan, on the far left by himself.

Yucho Chow Studio. 1915. “Quon On Jan Travel Agency, Maw Sun Hay – Owner.” Chung Collection. CC-PH-00425. B&W Photograph on matting. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0216673.

In this photo by Yucho Chow dating to the 1920s we see a group of sharp businessmen in front of the Quon On Jan company store. This photo shows more than just a snapshot of daily life in bygone days – this place was not just a business, but a lifeline for Chinese Canadians navigating immigration, trade, and community life. In this blog we will talk about some of the identified men in this photo and their lives in the context of the Quon On business. This company, alongside its affiliate Quon On Co., was instrumental in the maritime and railway travel networks linking British Columbia to Asia and the United States. At the helm of Quon On Jan was Mar June 馬駿 (centre, farthest on the right), also known by the name 馬心喜—a powerful merchant.

From Ow Ben, Toisan to East Pender Street

Earliest known photo of Mar June, C. 1905. US National Archives and Records Administration. Mar June, Chinese Exclusion Case Files. Box 341 Case 7027/70

Mar June’s origins trace back to the village of Ow Ben, Toisan (歐邊), in Kwonghoi township (廣海) Canton Province. His entry into Canada was recorded as May 1, 1895 on some documents, aligning with a later registration in 1909 upon arrival in Victoria from Seattle aboard the Canadian Pacific SS Princess Victoria. In that 1895 ledger he was listed as a merchant, aged 31, with no head tax recorded—a hint that he may have actually entered and become established before full enforcement of the Chinese Immigration Act. In US National Archives materials, there is ample evidence he travelled between Seattle, Port Townsend, Victoria, and Vancouver often during the years before the 1923 Canadian Exclusion Act was passed.[i]

By 1923, Mar June’s Quon On Jan firm was operating at 137-139 E Pender Street, sharing space with the Ma Gim Doo Hung (馬金紫堂 Mah Family Society). He most likely had a major role purchasing this plot of land and establishing the Mah clan’s hall on this prominent stretch of Chinatown’s commercial thoroughfare when they moved from a rooming house on Cambie St in 1920. This building remains a prominent historical landmark and continues to host the Mah Society of Vancouver. By 1924-1925 Quon On Jan moved to the address shown in the Yucho photo, 295 E Pender.

Detail from an ad and steamship timetable. The Chinese Times [Tai hon Kong Bo Ltd 大漢公報]. 民國十一年九月二十五日 [Sept 25 1922], Chinese Freemasons of Canada [加拿大洪門致公堂] Volume 21, No. 51. Pg. 8

Mar June in the 1920s or 1930s. US National Archives and Records Administration. Mar June, Chinese Exclusion Case Files. Box 341 Case 7027/70

A Brotherhood of Agents and Merchants

Quon On Jan was not an isolated operation. The wider Mah family and their associates formed a tightly knit web of clan, trade, business, and community roles.

Mar Chan (馬進 also known as Mar Kok Leu/Len, not pictured in the Chow photo), from Kwonghoi, was an elder among Chinese ticket agents in Victoria. Likely a mentor of Mar June, he had arrived in Victoria before the head tax via San Francisco, and as early as 1898 he was a longstanding cannery labor contractor. Like with the Yip family, power and money from Chinese ticketing developed alongside control over where indebted labourers worked through perilous contracts, especially in canneries and farms. Eventually Mar Chan became the head of all Chinese agents for the Blue Funnel Line through both Quon On Co. and Quon On Jan. His business firm and family compound at 529 Cormorant Street, Victoria became a key address used by many Chinese workers registering under the Exclusion Act. He retired to China, his gold mountain dream, in 1928 at the age of 80, after 57 years in Canada. His departure would align with a new generation of brokers, ticket agents, merchants and translators arriving at the forefront of Chinatown life.[ii]

Mar Chan retiring to China. Mar Chan AKA Mar Kok Yen “Records of Entry and Other Records” 1928-06-06/1930-09-11, Microfilm, Canadian Immigration Service, RG 76, T-16586, Image134, CI 9 #053730, Library and Archives Canada.

One of these up-and-comers was Mar Yee Why 馬余槐/淮 (centre, second from left of the four), possibly a cousin or associate of Mar June. Known later as Fred Bing Yee, he arrived in 1918 on the CPR Empress of Japan and began work as a passenger agent for Quon On Co., frequently traveling between Victoria and Vancouver. He journeyed to Seattle throughout the harsh Exclusion era in his private car, connected to Quon On’s operations. His comparative ease of travel across this rigid border often hostile to Chinese is noteworthy; Yee even returned from China in 1933 aboard the SS Ixion in second class—a rarity for Chinese Canadians, but fitting for someone deeply involved in international travel logistics.[iii] He later served as an accountant for the Young Fong Co. and passed away in 1963, survived by his wife, two sons, and a daughter.

The Rise of a Power Couple: Frank Mah and Mary Lam

As the 1930s approached, Frank Mah Fook Shung 馬福崇 emerged as a vital figure in the evolution of Quon On. He married Mary Lam, the daughter of Chung Ling Lam of the Hong Wo store in Richmond, in 1931. Around this point the Quon On partnership dissolved, with Quon On Co. of Victoria and Vancouver continuing as Blue Funnel Agents under Frank’s management, while Quon On Jan became American Mail Line and Dollar Line Agents, with Mar June remaining CNR ticketing agent.

Us National Archives and Records Administration. Frank Mah Fook Shung. Chinese Exclusion Case Files. Box 341 Case 7027/91

Initially the couple lived above Quon On Co.’s new address at 254½ Pender St, but later moved to the Cumberland Apartments on 14th Ave, making the couple early Chinese Canadian residents of Vancouver’s West Side, contemporaries of Tong Louie and Geraldine Seto in Point Grey. The Mah’s became known for their hospitality, hosting dignitaries and leaders of Chinatown as key parts of Vancouver “society life.”

Mary Lam Travelling to the US with her husband. Us National Archives and Records Administration. Frank Mah Fook Shung. Chinese Exclusion Case Files. Box 341 Case 7027/91

Frank was the English Secretary of the Chinese Merchants Association and a prolific presence in the English newspapers of the time. He coordinated the mass exodus of poor Chinese elderly “bachelor” men post-repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1947. Quon On’s reputation had remained strong into the post-war period, with the firm acting as agent for American President Lines, one of the only lines Chinese Canadians who wished to return to China for retirement could take home—particularly as CPR limited its passenger service from BC.

Frank Mah, centre beneath the Republic of China flag with unidentified Chinese woman. Detail from Soroptomist club of Vancouver [Chinese Appreciation Dinner] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11023, Chung Collection, 24 Feb. 1942. B&W Photograph

A Cultural Legacy

Mary Mah was much more than a travel agent. She was a member of the Soroptimists Club, active in the Pender Y, and taught Cantonese cooking at UBC’s Home Economics building as part of extension courses. She was a supporter of the Chinatown News magazine through her frequent purchase of advertisement space, and was a noteworthy bridge between early local born Chinese and those following in the 1940s and 1950s. These efforts helped broaden understanding and appreciation of Chinese culture in British Columbia during the 1960s.[v] She lectured widely on art, politics, and the cosmopolitan life of Hong Kong.

In 1960, Quon On Co. found itself peripherally involved in the RCMP’s sweeping investigations into “paper sons.” While the company did not engage in document fraud, it occasionally referred inquiries about getting fake documents to George Lim, Mary’s brother and head of Hong Wo store, which managed farms and cannery contracts.[vi]

The Final Chapter

Though Quon On World Travel—the company’s last iteration—likely ended operation during the COVID-19 pandemic, the spirit of the original firm endures. Its legacy lives on through archives, oral histories, and the memories of thousands whose journeys it helped facilitate—across oceans and generations.

Mary Mah passed away on October 21, 1990, just shy of her 90th birthday. She and Frank Mah are buried at Mountain View Cemetery, as well as Mar June and his wife Jung Shee, whose work through businesses like Quon On shaped the Chinese Canadian experience.[vii]

City of Vancouver Planning Department, [438-440 Main Street – Quon On Co. Ltd. Travel and Alexander Beauty Salon], July 1976, COV-S644-: CVA 1095-13756, Box F19-E-02 folder 7. B&W Photo Negative. Copyright City of Vancouver.

Footnotes

[i] US National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle branch. Mar June. Chinese Exclusion Act Case files, Box 341 Case 7027/70.

[ii] Mar Chan had at least three children, and likely had multiple wives as many merchants did. Known descendants are: Mar Kai Kong 馬啓, Mar Kai Kai Leong 馬啓亮, and Mar Hang So.

[iii] Library and Archives Canada, Passenger Lists: Vancouver and Victoria 1925-1935, Reel T-14903, June 3 1933, SS. Ixion

[iv] Chinatown News, Jan 18, 1959, page 11

[v] Chinatown News, Sept 3 1961, page 24

[vi] Library and Archives Canada, 2025, Access to Information Request A-2022-04779, Image 1190

[vii] Frank and Mary Mah had no children, and its unclear if Mar June and his wife or wives did.

No CommentsCanada’s Silk Trains

Posted on April 9, 2025 @11:34 am by Chelsea Shriver

“Nothing material, not even the mail, moves across oceans and continents with the speed of silk”

– George Marvin (The Sunday Province, 10 February, 1929)

We are delighted to announce a new display– Canada’s Silk Trains – which tells the story of the fast-paced silk train era. From the time that the first 65 packages of silk were unloaded in Vancouver on June 13, 1897, the race was on to find the fastest way to transport this valuable cargo across Canada and on to the National Silk Exchange in New York.

Between the late 1880s to the mid-1930s, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and later the Canadian National Railway, competed against time, the elements, and each other to transport silk to eastern markets. Insurance rates for silk were charged by the hour, incentivizing the rail companies to pursue faster and faster transportation times.

Despite the high speeds of the silk trains, there were very few accidents. The most well-known incident occurred on September 21, 1927, when a silk train derailed just beyond Hope, British Columbia, sending 4,500 bales of silk into the Fraser River. This accident was reported in newspapers at the time, and later provided the inspiration for the picture book Emma and the Silk Train. Images of the accident are not common, and so we were excited to identify two confirmed photographs (and one suspected photograph) of the crash in the newly available Price family collection. The display features books, photographs, and newspaper articles from across UBC Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections.

Canada’s Silk Trains is on display in the Rare Books and Special Collections satellite reading room on level 1 of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre and can be viewed Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. through July 4, 2025. For more information, please contact Rare Books and Special Collections at (604) 822-2521 or rare.books@ubc.ca.

References

Lawson, J. (1997). Emma and the silk train. (Mombourquette, P. Illus.). Kids Can Press (PZ4.9.L397 Em 1997).

Marvin, G. (1929, February 10). Fast as silk? [Microfilm of The Sunday Province, Vancouver, p.3]. https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/february-10-1929-page-43- 56/docview/2368257290/se-2

No CommentsLeon J. Eekman Materials

Posted on April 1, 2025 @1:35 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is part of RBSC’s blog series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

While the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung collection is best known for its large Canadian Pacific and Chinese immigration holdings, it also contains a wide variety of miscellaneous photos and materials from across Western Canada and Pacific Northwest. These can often allow us insight into lives that indicate the differences of experience between immigrant communities in BC, particularly between European colonists and other groups. Today we will be discussing the life of a Belgian-Canadian whose materials are found in the Chung Collection, Leon Eekman.

[Portrait of Leo J. Eekman] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11113. Chung Collection. 1909. B&W Photograph

Leon (Leondart, Leendert, Leonard) John (Jan, Jean, Jeens) Eekman was born on December 12, 1880, in Brussels Belgium, likely of Flemish background. He was from a large middle-class family with at least four brothers and one sister. When he was young he served as a sergeant in the infantry stationed in Liège, Belgium, before arriving in Canada around 1905, first to Manitoba and then settling in Victoria, British Columbia. A well-educated man with fluency in English, French, German, Flemish, conversational Dutch, and Walloon, Eekman soon found work as a language tutor. As a result he quickly became acquainted with colonial society, including the family of Chinese merchant Loo Gee Wing, subject of a previous blog. By 1908 he was also working as a surveyor and draftsman, well-established enough to employ a Chinese domestic servant, Ah Guan 關亞均, which was common among the colonial well-to-do.

This young man was a likely cook, gardener, and/or servant to Eekman or Holdcroft Family [Portrait of 關亞均, Ah Gwan] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11088. Chung Collection. 1908. B&W Photograph

His movements over the next few years suggest a complex transatlantic life; in 1909, he returned to Europe via New York City aboard the SS Oceanic, to attend the 1910 Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Bruxelles re-entering Canada in September 1910. He was at that point recorded as a tourist with no stated intention of permanent residence. Despite this, he made his way back to Victoria, where he had lived before. The differences between his easy crossing of borders and those of Chinese Canadians during a time of tightening exclusion are a noteworthy comparison here.

Front of Leon J Eekman’s 1910 Brussels International Exposition Pass. [Exposition Universelle & Internationale de Bruxelles 1910] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11108. Chung Collection. 1910. B&W Photograph on board

Shortly after his return, Eekman married Marion Holdcroft on November 10, 1910, in Victoria, after courting her in previous years. The wedding took place at the home of his in-laws, and through this union, he became connected to the Holdcroft family, a well-respected colonial lineage with English roots. Marion’s father, John Holdcroft, was the Assistant Surveyor of the City of Victoria, a role that Leon himself would later hold. Marion’s maternal relatives had been English merchants in Brussels, later starting a toy company. In their early years of marriage, Leon and Marion lived with her parents at 1268 Walnut Street, and Leon continued his work as a language tutor and surveyor. Around 1912, he became a naturalized British subject, further solidifying his ties to Canada. During this period the ability of Asian diaspora communities in BC to naturalize had been slowly restricted, likewise showing a diverging experience of legal belonging.

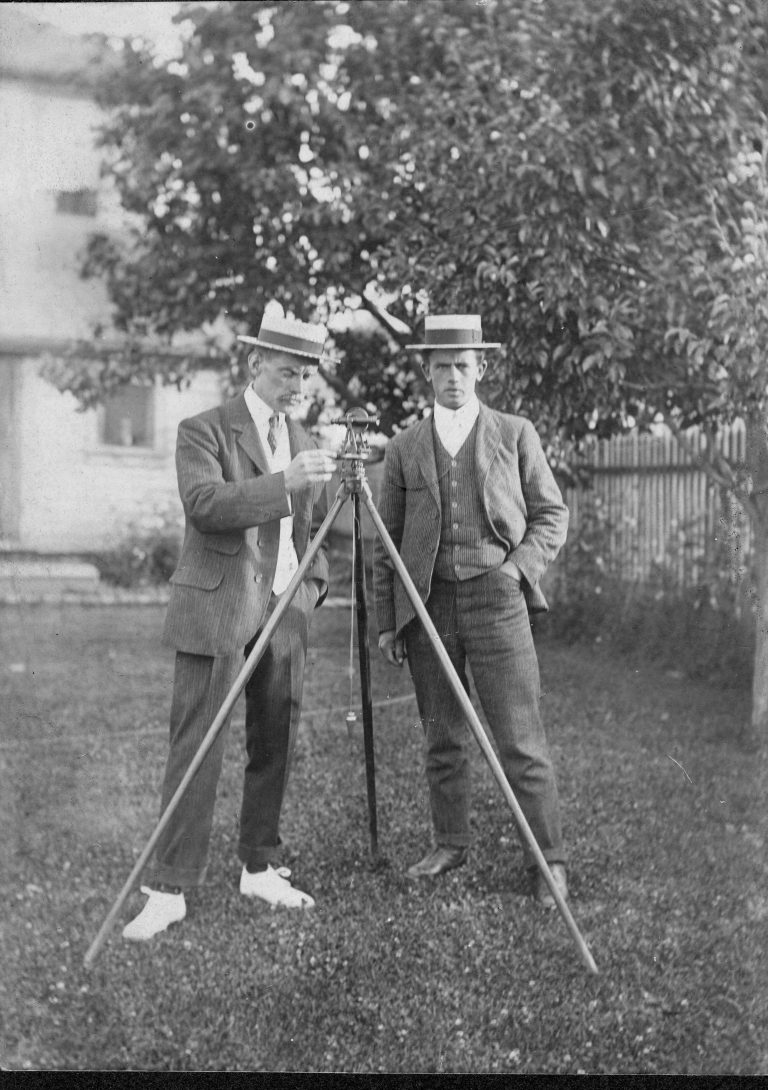

Leon (left) and likely Walter (right) Eekman surveying. [Leo J. Eekman] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11078. Chung Collection. 16 Jul. 1907. B&W Photograph

When World War I broke out, Leon enlisted with the Gordon Highlanders (50th Reg.) He later served in the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC), working under Colonel Murray McLaren at a field hospital in Étaples, France. His brother, Arie Eekman, also served in the same conflict in the Netherlands Army as a Militia Sergeant of the First Corp. Motor Service in Delft. Leon’s role involved the grueling and dangerous task of transporting wounded soldiers from the battlefield to medical facilities. His service was not without hardship; in October 1915, he contracted tuberculosis, which would shape the remainder of his service.

Leon Eekman in uniform, Nov 1914. [Portrait of Leo J. Eekman] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11080. Chung Collection. 21 Nov . 1914. B&W Photographic Postcard

Fearing anti-German sentiment in Victoria impacting his family due to his surname, Eekman wrote a public letter to the Victoria Daily Times from the front in June 1915, proclaiming his British loyalty and that of his family. By May 1916, his health had deteriorated to the point that he was medically discharged and sent to the Esquimalt Convalescent Home, followed by six months at the Tranquille Sanatorium. Still wanting to serve, Eekman was frustrated in his attempt to serve as a translator; he suspected discrimination due to his German-sounding name. His military discharge became permanent in July 1918, and he returned to civilian life in Victoria.

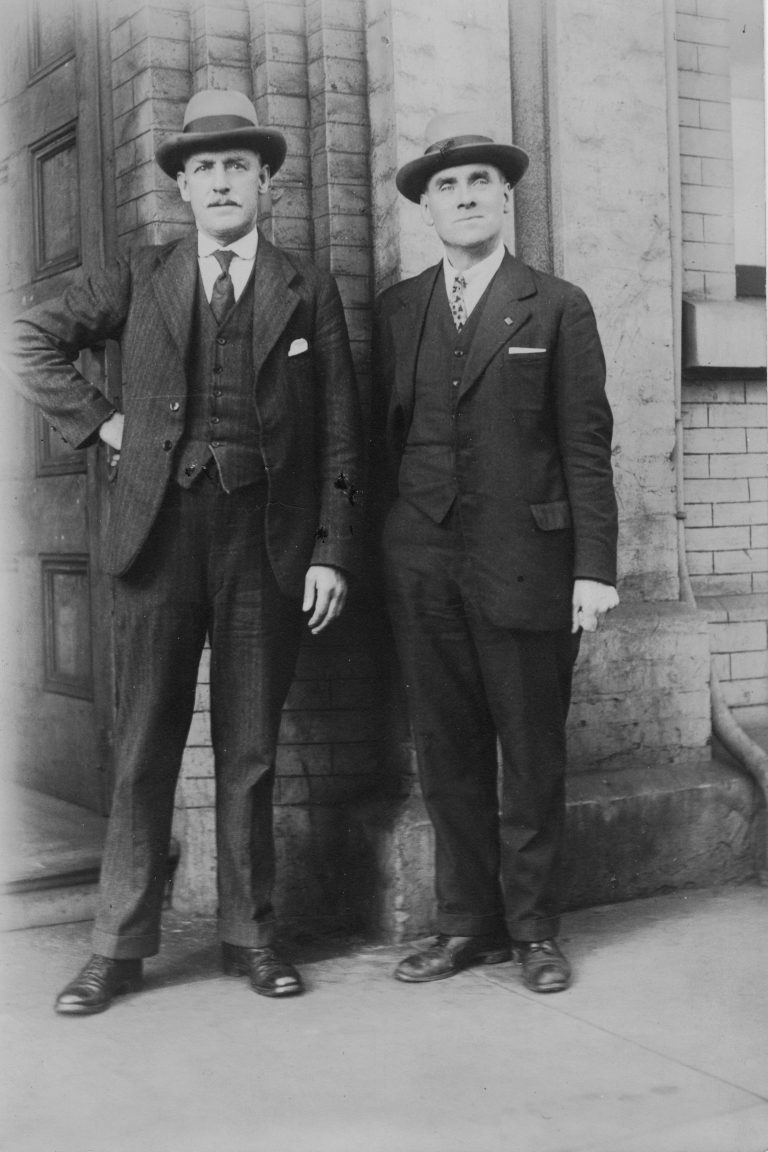

Leon (right) and colleague in front of Victoria City Hall. [Building and plumbing inspector and assistant building and plumbing inspector] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11092. Chung Collection. 1930. B&W Photograph

After the war, the Eekman family settled at 1303 Hillside Avenue. Leon petitioned the city to restore his pre-war position in the survey department, which he had left upon enlisting. This is a position that would have been excluded to non-whites by statute during this period. Over time, he became a provincial draftsman and later served as the Assistant Building Inspector for the City of Victoria. Beyond his professional life, he was deeply involved in religious and civic activities. A passionate evangelical Christian, he was active in the Shantymen’s Association, ministering to working men in remote (particularly mountain and coastal areas) of British Columbia. His religious fervor extended into his participation in the Canadian Protestant League, a controversial anti-Catholic organization. He frequently wrote newspaper columns and letters to the editor, engaging in heated theological debates, often garnering response letters about his all-to-frequent contributions.

Leon (2nd from left) and other mission workers of the Shantyman’s Association, Lake Cowichan BC, 1925. [Ye must be born again truck] RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11095. Chung Collection. 1925. B&W Photograph

During World War II, Eekman was appointed Acting Belgian Consul for Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii, where he assisted in the registration and conscription of Belgian diaspora men for the war effort. He requested every Belgian-Canadian house fly the Belgian and British flag to show loyalty. In April 1946, after 40 years of service with the city, he retired although his diplomatic work continued until 1947. He was a part of the welcome committee for Princess Juliana of the Netherlands when she visited Victoria, and in 1948 he was awarded the Order of Leopold II for his service to Belgium. In his later years, he continued to write emotional public letters and became a vocal critic of government policies, particularly opposing CMHC’s affordable housing initiatives in Saanich, which he felt discriminated against taxpayers. He also spoke out against age discrimination in the workforce.

The Eekman Family home served as Belgian Consulate during WWII. They displayed the two flags as Eekman had requested all Belgian Nationals do in his consular district. [Consulat de Belgique = Belgian Consulate] / L. J. Eekman. RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-PH-11090. Chung Collection. 1944. B&W Photograph

In 1949, Leon made a four-month trip to Europe, likely his first since World War I, visiting relatives in England and the Continent. By 1950, he had resumed his role as Honorary Belgian Consul for Vancouver Island. He remained an outspoken and controversial figure in the community until his death in 1954. His obituary in the Times Colonist on September 25, 1954, detailed his lifetime of contributions to Victoria and beyond. His memory lived on through his two surviving children, including Walter Gordon Eekman (born in 1912), continuing the family’s presence in Victoria for generations to come.

In 2005 some personal materials of Leon Eekman were purchased from Wells Books in Victoria, before being donated to the University of Manitoba Archives in 2015. They offer insight into how Dr. Wallace Chung may have acquired these materials.

While they can often challenge us, stories like that of the Eekman family allow us to view the range of experiences of BC residents across time. We invite you to engage with the digitized and physical materials of the Chung Collection and other holdings at Rare Books and Special Collections that may have relevance to genealogical or historical research.

Sources

University of Manitoba Archives, Leon J Eekman Fonds. https://umlarchives.lib.umanitoba.ca/leon-john-eekman-fonds

Leon John Eekman. Personnel Records of the First World War. Library and Archives Canada. RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 2848 – 49. Item 374921. Canadian Expeditionary Forces (CEF)

Victoria Daily Times and Victoria Times Colonist, Newspapers.com

No CommentsChinese New Year and “the Chinese Lily.”

Posted on January 29, 2025 @4:52 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is a special edition of RBSC’s series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

Happy Lunar New Year from the Chung Lind Gallery and the whole UBC Rare Books and Special Collections team! We wish everyone safe, healthy, and an auspicious year of the wood snake.

Chinese New Year celebrations have been a part of BC’s history and culture for at least over 150 years, enlivening both big cities and small towns with the sound of firecrackers, the rainbow colors of parades, bright red decorations, and the scent of special foods wafting in the air. There are many traditions and customs that vary both from region to region in China, but also family to family. Of the many traditions brought by the older waves of migration (lo wah kieu 老華僑), the visiting of flower markets (花市) and the cultivation of special lucky plants in the heart of the winter was and is cherished. One of the most prized plants was the Chinese Lily (水仙花), which is actually not a lily at all! This plant will be the topic of our celebratory blog today.

New Year’s Day in San Francisco’s Chinatown. 1881. Theodore Wores, artist. Oil paint on canvas. Collection of Oakland Museum of California. Gift of Dr. A. Jess Shenon.

Known by many names, including the bunch-flowered daffodil, Chinese sacred lily, cream narcissus, and joss flower, Narcissus Tazetta was brought to North America by Chinese workers during the California Gold Rush. The plant itself is native to the Mediterranean and was brought to China along the Silk Road before the Tang Dynasty. The early Chinese migrants to North American called it Sui Sin Fa “Water Fairy Flower,” a name likely derived from the Greek myth of Narcissus, which gave the flower its English name. Bulbs of the beautiful, highly fragrant flower were grown in Zhangzhou 漳州 Fujian 福建 and exported to Chinese communities all around the world. From there, it can be found naturalized in the fields, abandoned gardens, and Chinese cemeteries wherever Chinese were found in North America and wherever climate permits.

Yuen Fong Co. Ltd. 元豐公司. Nov 1962. “元蘴公司 = Yuen Fong co. ltd.” Iss 18. Vancouver, BC. UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-TX-307-1. Pg.1

The flower was prized because of its tight bunches of blooms and strong scent that grew when planted in shallow dishes in late October-Early November; they would ideally bloom right as Chinese New Year began. Multiple blooms from one bulb also had symbolism of plenty and abundance. They decorated homes, businesses, altars, and even photo studios, where they were used as a lucky prop for portraits sent back home during the New Year celebrations.[i]

In this formal portrait, likely the son of a wealthy merchant, notice the Chinese lilies to the side.

Unknown Photographer. 1910. “Chinese Boy.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00269 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0217964.

In BC, the flowers are found as early as the 1890s, though they most likely arrived earlier. In 1892, The Victoria Daily Times shared that the pet goat of a “well-known and justly popular saloon-keeper” had perished after eating a Chinese lily bulb gifted to the family by an employee for the new year.[ii] During the Chinese New Year season, Chinese servants would demand (and receive) vacation time, Chinese societies and social clubs would gather for banquets, and family businesses would give out gifts to partners, customers, and friends. The flowers and bulbs of the lily were very popular, leading to the following quote:

“Genii of the Water: All those who have visited the Chinese during the New Year festivities have noticed the sweet-scented flowers of the Chinese water lily, shin sin fa, water sprite flower, or water genii flower, which the Chinese always have in full bloom at their New Year. These, with branches of almond blossoms, pomelos and oranges, artificial flowers of paper and tinsel, a Chinese dragon embroidered in gold on a silken cloth, form the principal decorations of the Chinese New Year’s table, while upon it are Chinese candies, sugared fruits, laichis (Chinese nuts), and watermelon seeds, all in a lacquered box, called tsun hop, or complete box. These confections, and tea, wine and tobacco, are offered to all callers.”[iii]

By 1902, the plant was so popular among the non-Chinese community that a full page spread about how best to raise them was published in the Vancouver Daily News Advertiser. Ads for the bulbs were found prominently printed in the November issues of Chinatown Vancouver import-export businesses up to the 1970s, including the ad with instructions below.

Yuen Fat Wah Jung Co. 元發公司. Nov 1954. “Yuen Fat Wah Jung co. = 元發公司” Vancouver, BC. UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-TX-307-26

We wish you all a happy new year!

花開富貴 瑞氣呈祥

Further Reading

Hodgeson, Larry. “The Little Bulb That Conquered China” November 8 2017, Laidback Gardener Blog. https://laidbackgardener.blog/2017/11/08/the-little-bulb-that-conquered-china/

Footnotes

[i] Adams, John D. Chinese Victoria: A Long and Difficult Journey. Victoria, BC: Discover the Past, 2022.

[ii] The Victoria Daily Times Feb 15 1892 Pg.5

[iii] Vancouver Daily World, March 23 1901, Pg.2

Stories of Chinese Sailors in Canada’s Maritime History

Posted on January 18, 2025 @3:07 pm by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is long-form edition of RBSC’s blog series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

Early Entrances into Maritime Labor

The history of Chinese men working in the maritime industry in Canada stretches back to the initial arrival of the community to these shores in 1788. That year, 50 Chinese carpenters arrived in Yuquot as part of the Meares Expedition, hired for their skills in nautical repairs and as shipwrights.[1] As trans-Pacific connections developed between Asia, Oceania, and North America, Chinese sailors remained a part of the maritime workforce along the North American Pacific Coast. However, by the late 1800s they were more often assigned to the most grueling roles. Anglo-American culture had stereotyped Chinese as unreliable due to their lack of English, or because of their “superstitions” about weather or bad luck omens.[2]

Depicts six Chinese men in white jackets, possibly cooks and stewards, standing on the deck of the Iroquois. Unknown Photographer. 1920-1929. “Iroquois Crew.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00126. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0217393.

With steamship travel increasing in the 1880s, out-of-sight Chinese firemen (also called coal stokers or boilermen) worked in the engine rooms enduring oppressive heat, while cooks, stewards, and cabin boys toiled above in the crowded, tight kitchen galleys and passageways. On Canadian Pacific (CP) steamships, Union Steamship Company vessels, and other lines associated with Robert Dollar’s shipping empire, Chinese seamen were indispensable, but usually laboured in these segregated, unseen roles. Aboard the CP Empress liners, for example, they prepared their own Chinese meals in separate kitchens, resided in isolated quarters near the “Oriental Steerage Class” passengers, and were relegated to the back of the ship—both physically and metaphorically.[3]

Crew of an unknown vessel with one Chinese man. Unknown Photographer. 1910. “Crew Aboard a Steamship.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00128. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0217720.

Despite these hardships, Chinese mariners—from engine-room firemen to “tea boys”—built social and cultural connections across the British Empire, of which the BC coast was only one hub. Chinese sailors were also a common sight on Japanese imperial lines, such as Nippon Yusen Kaisha, that sailed for North America. While initially predominantly Cantonese, soon men from Zhejiang, Fujian, and other coastal areas joined crews around the world. This network of nautical workers also extended to the United States, which had its own Pacific ambitions and growing maritime empire.

Global Connections: From Liverpool to Hong Kong

As the 20th century dawned, the world of Chinese sailors continued to expand, linking British ports such as Liverpool to colonial hubs like Hong Kong. Liverpool’s docks, for example, became a focal point and safe haven for Chinese seamen post-World War I. The Blue Funnel Line, headquartered in Liverpool and one of the most active shipping companies in BC Chinese migrant traffic, hired many of these men to work onboard their vessels.[4]

Migration is never a simple equation; through shipping White settlers to North America, Blue Funnel brought Chinese sailors to the UK, fostering a small multicultural maritime community in Europe. Organizations such as the UK-based Dragons and Lions group now preserve the legacies of mixed-race descendants from this era, whose ancestors suffered separation when the British government turned against these Chinese sailors, even after some served during both World Wars.[5]

A group of Chinese seamen outside a Chinese hostel in Liverpool, sign on the left indicates it as a meeting place of the Tsung Tsin Society for Hakka speakers. Bert Hardy. May 1942. “Chinese Hostel, Liverpool.” Picture Post. 1136. Getty Images via The Guardian. Accessed Jan 16 2025.

Hong Kong, a key node in this global web, was where many Chinese mariners found work, retired, or kept families and businesses ashore. Others joined secret societies, mutual aid associations or sailors’ institutes.[6] Some even joined criminal gangs to make some money on the side through smuggling.[7] Here also, many were radicalized into political involvement.[8] The Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, recognizing the potential power of sailors to smuggle subversive documents world-wide, formed the Lianyi Society 聯義社, also known as the Chinese Seamen’s Association, in 1910.[9] It then coordinated the spread of revolutionary ideology, fundraised, and even transported contraband weapons across the often otherwise-exclusionary borders of empires.

The 1922 Hong Kong Seamen’s Strike demonstrated the immense collective power of Chinese laborers, disrupting service by most major Pacific shipping companies, like Canadian Pacific. The strike’s influence reached far beyond Asia, as British Columbia’s newspapers anxiously speculated about similar uprisings, creating ripples of fear in the Canadian trade establishment about potential labor unrest on their shores.[10] We will most likely return to this critical event in future blogs.

This photograph of staff from the 34th voyage of the Empress of Japan lists all the white members by name and title, from the Chief Steward to the hairdresser and assistant storekeeper. All the Chinese members, the “first boys,” are unnamed. Most likely the Chinese cooks are not even shown. Sai Wo Studio. Hong Kong. 1935. “Catering Department R.M.S. Empress of Japan.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H Chung Collection. CC-PH-00329. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0216646.

The Grip of Exclusion Tightens

While history around Chinese Exclusion has focused mostly on its impact on migrants who intended to stay in Canada for longer terms, these laws also often explicitly target the freedom of movement of Chinese sailors. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, immigration policies in Canada and the United States increasingly show a deep discomfort of the role of Chinese seamen in foreign trade.[11] After 1900, laws tightened further. The 1906 British Merchant Shipping Act, introduced language requirements that sought to exclude South Asian and Chinese mariners, the so-called “coolie and lascar” sailors.[12] Later, U.S. legislation, such as the 1917 Asiatic Barred Zone Act and the 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act, imposed steep head taxes, mandatory photo IDs, confinement aboard boats at anchor, or even bond requirements on Asian seamen.[13]

Chinese Sailors at a hostel in Liverpool. Men lived in crowded, dirty conditions in unmaintained buildings in ports around the world, often close to the urban core or red light district. This transient, male-only environment is one that echoes with that of Chinese men in labour camps and SRO hotels, the so-called “bachelor society.” Bert Hardy. May 1942. “Interior Chinese Hostel, Liverpool.” Picture Post. 1136. Getty Images via The Guardian. Accessed Jan 16 2025.

By 1925, the British Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order compounded these restrictions by requiring non-white sailors to register and carry identity documents, with the goal to drive away as many Chinese, South Asian, and Black sailors from their international fleet. This was important in a Canadian context, as all the Canadian Pacific’s Empress liners were British-owned and registered. The Chinese Nationalist government also introduced measures in the 1930s and 40s mandating overseas Chinese to register if they wished to remit earnings home or re-enter China. These overlapping policies subjected Chinese sailors around the world to constant surveillance and financial strain.

Navigating Vancouver’s Waters

By this time, Vancouver’s port had been a crucial transit point for Chinese sailors navigating trans-Pacific routes since becoming the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1887. The city’s Chinatown became a sanctuary for mariners who jumped ship, using shared clan and hometown connections to integrate into Chinese communities across the province.[14] From the 1870s to the 1970s, thousands of sailors disembarked illegally this way in North American ports like Vancouver, Halifax, and New York, often evading strict immigration policies.[15]

This very rare CI 46 Certificate was carried by Luke Ko, born to the prominent Ko Bong family of Victoria, in the 1930s. His photo was on the other side. It forms part of The Paper Trail Collection at UBC RBSC, where you can learn more about his life. Dominion of Canada. Department of Immigration and Colonization. Chinese Immigration Service. Victoria, BC. 18 Jan 1932. “C.I.46 Certificate of Luke Ko Bong.” UBC RBSC Paper Trail Collection. RBSC-ARC-1838-DO-0459r. Courtesy of the Ko Bong Family.

The Canadian Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 added layers of bureaucracy for Chinese mariners.[16] Shipping companies were required to list all Chinese crew members on special ledgers, with heavy fines imposed on the company for any absentees. Despite this, sailors found ways to subvert these measures, purchasing fraudulent identity documents to remain in Canada or assuming the identities of Chinese Canadians who had paid the head tax or were locally born. The stories of these “paper sons” exemplify the resourcefulness of Chinese mariners in circumventing exclusionary laws.

During World War I, Chinese mariners began to appear in more visible roles, above deck on Canadian Pacific’s Empress ships. Some became closer friends and coworkers to senior officers, like the Chief Stewards, Ships’ Surgeons, and Head Purser (Paymaster.)[17] These closer connections and better jobs sparked a backlash from white sailors’ unions and exclusionists, especially in British Columbia.[18] Debates in Canada’s House of Commons during the 1930s centered on whether the company should be penalized for hiring Chinese sailors over white Canadians while they received a large government subsidy.[19] While a 1937 recommendation to cut federal aid for Canadian Pacific failed, it highlighted the entrenched racism these workers faced.[20]

Acts of Resistance

Despite these challenges, Chinese sailors fought back. Beyond the 1922 Hong Kong Seamen’s Strike, there are many smaller examples of collective action. Sailors staged walk-offs, work slowdowns, or shared political and immigration information with Chinese migrants en-route to their new lives. The Lianyi Society (Chinese Sailors Society), working with popular Cantonese opera troupes, smuggled letters from revolutionaries and literature to communities around the world.[21]

Later, during World War II, 83 Chinese seamen in Halifax were detained for seven months after demanding hazard pay for navigating the treacherous North Atlantic warzone.[22] In February of 1942, 14 more Chinese seamen from Hong Kong escaped the Nova Scotian port after being rescued from a torpedoed ship and brought to the immigration station ashore, costing their employer 21,000 CAD in forfeited bonds under the Exclusion Act provisions.[23] That same year, two dozen Chinese crewmen in Vancouver sued their employer for false imprisonment when they were handed over for immigration detention after walking off the boat for higher wages.[24] Although these efforts often ended in deportation or legal defeat, persistent acts of resistance underscore Chinese sailors’ determination to assert their rights.

Lee Ah Ding (left) and Yee Chee Ching, Chinese seamen from a British freighter, try typical American food for the first time. Chinese sailors were denied shore leave in the USA even during wartime, until diplomatic negotiations loosened restrictions slightly. It is unclear if Canada also relaxed its harsh laws. United States Office Of War Information, Gruber, Edward, photographer. First Chinese seamen granted shore leave in wartime America. New York, USA. Sept 1942. Photograph. US Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017693642/.

Sustaining Community and Culture

The contributions of Chinese sailors extended far beyond their roles aboard ocean liners, the merchant marine, or international trade. Traveling through global waters, they brought news and goods to isolated Chinese workers in canneries, sawmills, and mining communities along British Columbia’s northern and central coast.[25] Cooks on coastal ferries, steamers, and mail ships, like famous author Wayson Choy’s father, endured long hours away from family with the hope of saving.[26] Often they worked alongside their “cousins and uncles” from the same village clan, and when one retired, either to the village in China or to a Canadian Chinatown, they sought to replace them with another relative in need of work.

Two Chinese cooks and crew with three white children from Rivers Islet, BC on steamer to Metlakatla BC (a Tsimshian village). Chinese coastal ferry workers were a critical part of maritime connections between isolated settlements along the vast Pacific coast. Unknown Photographer. ca 1908. “Fred Grant and family on the S.S. Coquitlam” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC-PH-11350.

Post-War Transitions and Decline

After World War II, changes in the maritime industry and immigration policies transformed the lives of Chinese sailors. The American Chinese Exclusion Act ended in 1943, with the Canadian Chinese Exclusion Act following in 1947, though strict quotas and restrictions remained in both countries. Many young men fleeing the Chinese Civil War joined ships to escape turmoil, hoping to find new opportunities abroad. Despite their willingness, these working-class men were often passed over as precious quota spots were filled by wealthy and educated elites, unless they had a family member in Canada who could try to help them come.

In the 1950s and 1960s, shipping companies like the President Lines depicted here tried to update their fleets to reflect the sleek modernist tastes of the time. This American company had strong traffic from Chinese Canadians post-Exclusion as an affordable way for elderly bachelors to retire in China, or for families to come to North America for reunification. Eventually, passenger service on these boats was supplanted by air travel and the company pivoted to shipping. Palmer Picture. ca 1950. “Chefs and Servers in a Dining Area.” UBC RBSC Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection. CC-PH-11365.

The decline of trans-oceanic steamship routes further reduced opportunities for Chinese mariners. With travelers increasingly turning to air travel, shipping moved away from passenger traffic and towards shipping containers, reducing the need for cooks on vessels. Travel to China also steeply declined following the Korean War embargoes, although ties to Hong Kong remained strong. By the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese sailors in Canada were primarily employed as cooks and stewards on BC Coastal Ferries. Relatives, former classmates, and friends would vouch for new arrivals; this ability to support one another is a contributing factor to why Chinese cooks had a virtual monopoly over coastal vessels until the 1970s. For some, this was their first job in Canada, and a way to learn English and culinary skills that would allow them to open their own businesses; a path to the middle class. Programs like the 1960 Chinese Adjustment Statement provided amnesty for those who had entered Canada illegally, many of whom were former sailors.

Conclusion: Contemporary Parallels

Today, Canada’s ports continue to host crews from around the world, many of whom endure exploitative working conditions reminiscent of earlier eras. Most ships visiting Vancouver operate under “flags of convenience”—registered in countries with lax labor and safety standards—leaving their multinational crews vulnerable. Most modern sailors come from countries previously colonized by European powers. Advocacy groups continue to work to improve conditions for these modern mariners, offering legal aid, welfare visits, and essential supplies.

The history of Chinese sailors in Canada’s maritime industry reveals a story of perseverance and adaptability amid systemic racism and exploitation. Their labor was instrumental in connecting Canada to the global economy, yet their contributions remain underrecognized. By examining their struggles and achievements, we not only honor their legacy but also shed light on the ongoing challenges faced by seafarers worldwide.

If inspired to assist, consider supporting organizations dedicated to improving the welfare of sailors visiting Canadian ports, ensuring their dignity and rights are upheld in the modern era.

Footnotes

[1] You can learn about this history at the Chung Lind Gallery

[2] For example, this story about the Batavia in The Vancouver Daily News Advertiser

Thu, Aug 09, 1888 ·Page 3

[3] The Chung Collection holds many versions of blueprints of the Empress of Asia. Some show annotations which indicate the quarters of Chinese workers and passengers, located in segregate settings near the stern.

Canadian Pacific Railway Co. 1945 “Empress of Russia and Empress of Asia general arrangement plans” RBSC-ARC-1679-CC-OS-00119

[4] Records related to Blue Funnel line can be found at UBC RBSC and City of Vancouver archives. Their ship names are commonly seen on the General Register of Chinese Immigration and head tax certificates. The Liverpool Maritime Museum holds some of the company records in their archives.

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/records-of-blue-funnel-line-ocean-steam-ship-company

[5] https://dragonsandlions.co.uk/

[6] Kwok-Fai Law, Peter. “The Political Pragmatism of Steamship “Teaboys”: Reassessing the Chinese Labor Movement, 1927–1934.” Twentieth-Century China 46, no. 3 (2021): 287-308. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/tcc.2021.0025.

[7] Headlines about drug smuggling from sailors are common in BC and other North American ports through the 1970s. It is also a trope in some Hong Kong cinema films.

[8] Glick, Gary W. 1969. “The Chinese Seamen’s Union and the Hong Kong Seamen’s Strike of 1922.” Masters Thesis. History Columbia University. New York City, USA.

[9] In 1910 Lianyi was founded in San Francisco. Soon after a hub in Yokohama in a tailor shop. By 1915 central offices were in Shanghai, then Hong Kong, then Guangzhou. Operations ceased in 1927. The union used fake corporations to obscure their operations. (Huang Langzheng 黃郎正, “Brief Account of the Chinese Ocean Seamen Union 聯義社之概述” Kwangtung Culture Quarterly 廣東文獻季刊. Iss. No. 2. June 1, 1973

[10] For example: The Vancouver Sun Tue, Feb 28, 1922 ·Page 11; The Vancouver Sun

Sun, Jul 23, 1922 ·Page 12

[11] Canadian Head Tax in 1885 had no provision for Chinese Sailors, so their status was a gray area. In 1902 there was an attempt to land a Chinese crew of 30 in Victoria to staff a Seattle Ship on way to Russian Far East, which the government blocked through an administrative order (The Vancouver Semi-Weekly World, Dec 26 1902 Pg.5.) From 1882-1902, it was also a gray area for Chinese sailors in USA Exclusion laws. From 1903-1917 shipping lines to USA had to post 500 dollar bond forfeited if Chinese sailors hopped ship.

[12] Urban, Andrew. 29 Oct 2018. “Restricted Cargo: Chinese Sailors, Shore Leave, and the Evolution of U.S. Immigration Policies, 1882-1942.” Online Article. Rutgers University. New Jersey, USA. Accessed Jan 17 2025. https://t2m.org/restricted-cargo-chinese-sailors-shore-leave-and-the-evolution-of-u-s-immigration-policies-1882-1942/

[13] Urban, Restricted Cargo. 2018

[14] The Montreal Star Mon, Jul 11, 1910 ·Pg. 4

[15] Pegler-Gordon, Anna. 2021. Closing the Golden Door: Asian Migration and the Hidden History of Exclusion at Ellis Island. 1st ed. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/9781469665740_pegler-gordon.

[16] Library and Archives Canada. Statutes of Canada. “An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration, 1923.” Ottawa: SC 13-14 George V, Chapter 38. Sec. 25

The text of the Act allowed for Chinese sailors to land and then ”re-ship” with other outbound employment, but days after it was enacted this freedom was repealed by Order in Council (E.C.1275) and cash bond instated.

[17] Some would pool together money for an engraved plaque when these men moved to other boats or retired after long service. (Victoria Daily Times Jan 3 1933 Pg.8)

[18] Survey of Race Relations. 1924-1927 “Testimonial meeting on the Oriental, I.W.W. Hall, Cordova Street” Stanford University. Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. Box: 24, Folder: 16. Accessed Jan 17 2025. https://purl.stanford.edu/bd797xr7521

[19] Letter to Editor supporting Chinese sailors (Vancouver Sun Feb 10 1937 Pg 4)

Criticism of letter above: (Vancouver Sun Feb 13 Pg 4)

[20] House of Commons Journals, 18th Parliament, 2nd Session : Vol. 75 Pg.81-82

[21] A comprehensive history of Lianyi Society was published by Huang Langzheng in Hong Kong in 1971 titled 聯義社社史. The Lianyi Society overlapped with Hong Kong’s 八和會館opera union. There is an interesting connection through Red Boat travelling operas 紅船 , which link sailors, opera, kung fu, and secret societies.

[22] Meredith Oyen, “Fighting for Equality: Chinese Seamen in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1939–1945” Diplomatic History, Volume 38, Issue 3, June 2014, Pages 526–548, https://doi.org/10.1093/dh/dht106

Mention also of this incident in William Lyon Mackenzie King’s journals.

[23] Regina Leader-Post, Feb 21, 1942 ·Page 19

[24] The Vancouver Province Oct 21, 1942 ·Page 8

[25] Christenson, Neil H. “All the Princesses’ Men: Working for the British Columbia Coast Steamship Service 1901-1928” Masters Thesis. Eastern Washington University. Spring 2022. EWU Digital Commons. Accessed Jan 17 2025.

[26] Choy, Wayson. “Paper Shadows: A Chinatown Childhood.” Toronto: Penguin Books, 2000.

This path was also true for writer Fae Myenne Ng, as recounted in Ng, Fae Myenne. “Orphan Bachelors: A Memoir : On being a Confession Baby, Chinatown Daughter, Baa-Bai Sister, Caretaker of Exotics, Literary Balloon Peddler, and Grand Historian of a Doomed American Family.” New York: Grove Press, 2024.

No CommentsNew Years 1932 Menu, the Empress of Britain World Cruise

Posted on January 3, 2025 @11:15 am by Andrew R. Sandfort-Marchese

This blog post is special edition of RBSC’s new series spotlighting items in the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection and the Wallace B. and Madeline H. Chung Collection.

Happy New Year from the Chung Lind Gallery and the whole UBC Rare Books and Special Collections team!

Canadian Pacific Railway Company, and Lawrence Crawford. 1932. “Empress of Britain World Cruise New Year Dinner 1932.” M. Chung Textual Materials. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0373316.

As we glide into 2025, may we all have a chance to experience some of the finer things in life, as these passengers aboard the 1932 Empress of Britain world cruise certainly did for this New Year’s Day feast. With a ten-course meal plus dessert, there was ample opportunity to ring in the New Year with a cornucopia of plentiful food.

The cover of this advertising pamphlet for the 1931-1932 World Cruise features an Indonesia Shadow Puppet.

Canadian Pacific Steamships. 1931. “Empress of Britain World Cruise 9th Annual.” Advertisements. Chung Textual Materials. USA : Unz & Co. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0362227.

Pg.1

The Empress of Britain was the largest ship in the Canadian Pacific Steamship Co and considered the most luxurious. On Dec the 3rd 1931, she departed New York to begin her 128-day world cruise. During the Depression, this was a luxurious journey only very few could afford, with tickets starting at around $2000 USD per person at the lowest fare ($66,700 CAD in Jan 2025.) Posters and pamphlets advertised the “exotic locales” and opulent Jazz-Age interiors of the vessel, hoping to nab elite leisure visitors from the Anglo-American upper-crust. Servants like valets and maids could travel for lower rates, in cabins deeper in the ship. There were many shore excursions if you chose to leave “the floating palace.” On this voyage, the passengers spent ate their New Years dinner ashore on the banks of the Nile River near Cairo and the Pyramids, having spent Christmas in Mandatory Palestine.

Canadian Pacific Steamships. 1931. “Empress of Britain World Cruise 9th Annual.” Advertisements. Chung Textual Materials. USA : Unz & Co. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0362227.

Pg. 4

The menus of CP Empresses leaned strongly towards continental cuisine, especially French, with an emphasis on meat, seafood, and rich sauces. Between you and me, for this meal I’d skip the chicken in braised celery and clear sauce and go for the Tournedos Rossini (filet mignon pan fried in butter with a topping of pate, black truffle, and Madeira wine sauce.) On Pacific voyages, the Chinese chefs would prepare Chinese cuisine for the majority-Asian steerage passengers.

Canadian Pacific Steamships. 1931. “Empress of Britain World Cruise Fares.” Advertisements. Chung Textual Materials. United States : Canadian Pacific Railway Company. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0372252.

Pg.3

Keep an eye out for new stories from the Chung and Lind Collections throughout 2025, and for new programming to come!

Let us know if you would like more blogs about food and the Chung collection!

Further Reading

Turner, Gordon. (1992). Empress of Britain

No Comments